Jericho, Texas: Where the Walls Fell, Not by Trumpet, But by Time and Dust

The Texas Panhandle, a vast expanse where the sky stretches endlessly and the wind hums a constant, ancient tune, holds countless stories. Some are of booming oil towns, others of resilient ranching communities. But many more are tales of places that once pulsed with life, only to recede into the quiet dignity of memory. Among these spectral settlements, one name stands out, heavy with biblical resonance: Jericho, Texas.

Unlike its ancient namesake, the walls of Jericho, Texas, did not fall to the blare of trumpets or the might of an invading army. Instead, they succumbed to the relentless march of time, the fickle hand of economic change, and the devastating, slow-motion catastrophe of the Dust Bowl. Today, what remains of Jericho is a poignant testament to the boom-and-bust cycles that defined much of the American West, a ghost whispering tales of forgotten dreams on the Panhandle wind.

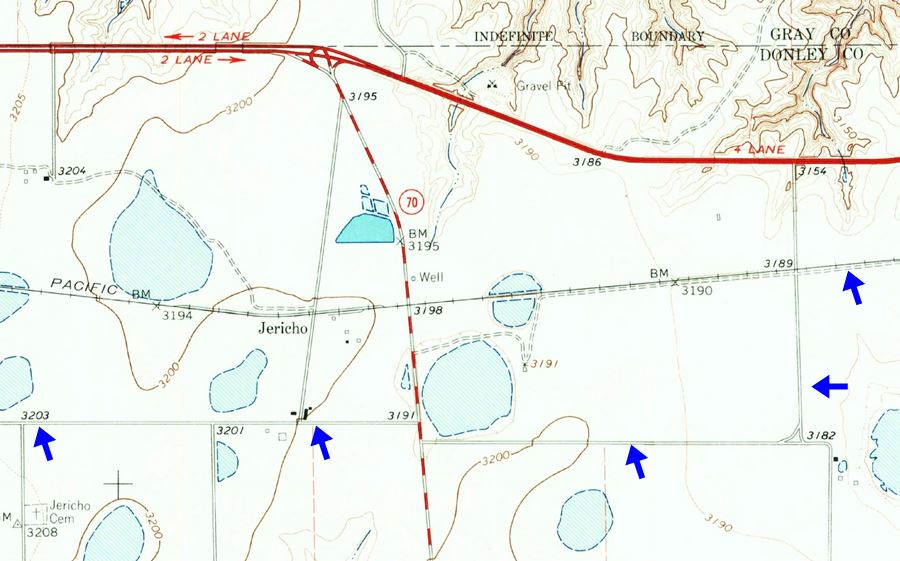

Driving east on U.S. Highway 60 from Amarillo, the landscape gradually flattens into an almost oceanic expanse of prairie. It’s a land where distances are measured in horizons, and human settlements appear as tiny, vulnerable islands. As you approach the Roberts County line, a few skeletal structures emerge from the sameness – a collapsing frame building, perhaps a weathered sign, and the unmistakable, brooding presence of an abandoned grain elevator. This is Jericho, a place where the past isn’t merely remembered; it’s palpable, etched into the very fabric of the crumbling infrastructure.

The story of Jericho, like many towns in this region, begins with the railroad. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, steel rails were the lifelines of progress, cutting across the untamed frontier and giving birth to new communities at regular intervals. The Fort Worth and Denver City Railway laid its tracks through this part of the Panhandle in 1887, and by 1902, a siding and a section house had been established. This nascent settlement needed a name. Local lore suggests the name "Jericho" was chosen by a railroad official, perhaps drawn to its biblical echo of a walled city, hoping to inspire a sense of permanence and prosperity.

And for a time, prosperity did come. Jericho quickly became a vital shipping point for the vast quantities of wheat, cotton, and cattle produced by the surrounding farms and ranches. Grain elevators, towering sentinels of the agricultural economy, rose against the flat sky, their bins filling and emptying with the rhythm of the seasons. A post office was established in 1902, followed by a general store, a blacksmith shop, and eventually a school. By the 1920s, Jericho was a small but thriving community, home to a few hundred souls who lived and worked within its modest boundaries. It was a place where neighbors knew each other, where children walked to a one-room schoolhouse, and where the arrival of the train was an event.

"It wasn’t a big city, not by any means," recalls an old newspaper clipping from the era, describing Jericho’s peak. "But it was home. It was where you got your mail, bought your flour, and shared a cup of coffee. It was everything you needed in a day’s ride." This was the golden age of Jericho, a brief but vibrant chapter carved out of the vast, indifferent prairie.

Yet, this promise was fleeting, built on the fragile foundation of an agricultural economy and a climate that could turn hostile with terrifying speed. The 1930s brought the most devastating blow, one that would redefine the Great Plains and etch itself into the American psyche: the Dust Bowl.

The "black blizzards," as they came to be known, were more than just dust storms; they were apocalyptic events. Decades of intensive farming, coupled with severe drought, had stripped the land of its protective topsoil. When the winds came, they lifted millions of tons of earth into the sky, creating towering, suffocating clouds that blotted out the sun, invaded homes, and choked life. For days, sometimes weeks, the Panhandle was plunged into an eerie, ochre twilight.

"You couldn’t see your hand in front of your face," recounted a survivor of the era, whose family once farmed near Jericho. "The dust got into everything – your food, your clothes, your lungs. It was like the land itself was weeping, and we were drowning in its tears."

The Dust Bowl was catastrophic for Jericho. Farms failed, crops withered, and the very ground on which the town stood seemed to turn against its inhabitants. People, desperate and destitute, began to leave. The population dwindled rapidly as families packed what little they had into jalopies and headed west, seeking a new life in California, a journey immortalized in John Steinbeck’s "The Grapes of Wrath." Businesses shuttered, the school saw fewer and fewer students, and the once-bustling grain elevators stood increasingly empty. The "walls" of Jericho, built of community, commerce, and hope, were indeed falling, not with a sudden crash, but with the slow, agonizing erosion of dust and despair.

A brief reprieve came in the late 1930s and 1940s, as rains returned and the land began to heal, aided by new conservation practices. But Jericho never fully recovered. Post-war agricultural mechanization meant fewer laborers were needed on farms, further reducing the local population. Improved roads and the rise of the automobile allowed residents to travel to larger towns like McLean or Pampa for goods and services, bypassing the small local stores. The consolidation of rural schools meant children were bused to bigger districts. Each development, seemingly innocuous on its own, chipped away at the reasons for Jericho’s existence.

Today, Jericho stands as a stark, poignant ruin. The post office closed in 1960. The school followed suit, its students absorbed into the McLean Independent School District. The grain elevator, once a symbol of life and prosperity, now stands like a lonely monument, its corrugated metal weathered to a dull rust, its windows empty sockets staring out at the unchanging plains. A few crumbling foundations mark where homes and businesses once stood. The only sound, apart from the occasional roar of a passing semi on US 60, is the ceaseless whisper of the wind, carrying with it the ghosts of voices long gone.

A drive through Jericho now takes mere minutes. There might be a handful of occupied residences, mostly trailers or small, older homes, their inhabitants choosing the quiet solitude over the bustle of larger towns. These few remaining souls are the silent custodians of Jericho’s memory, living amidst the echoes of what once was. They are often descendants of families who weathered the storms, literally and figuratively, and their connection to the land runs deep, a stubborn root in the parched earth.

Jericho is not unique in its decline. Throughout the Great Plains, hundreds of "ghost towns" dot the landscape, each with its own story of ambition, hardship, and ultimate surrender to the forces of nature and progress. But Jericho, with its evocative name, serves as a particularly potent symbol. It reminds us of the fragility of human endeavors in the face of environmental catastrophe and economic transformation. It speaks to the impermanence of even the most well-intentioned settlements, a reminder that not all walls are built to last.

As the sun dips below the horizon, painting the vast Texas sky in hues of orange and purple, the ruins of Jericho cast long, skeletal shadows. The wind picks up, rustling through the dry grasses and rattling the loose tin of abandoned structures. It’s a sound that seems to carry the murmurs of past lives – the laughter of children, the rumble of trains, the anxious whispers of farmers watching the sky.

Jericho, Texas, is more than just a dot on a map or a collection of dilapidated buildings. It is a living museum of the past, a silent chronicler of the American spirit’s enduring resilience and occasional defeat. Its story is a powerful narrative about the dreams planted in the unforgiving earth, the challenges faced, and the quiet dignity of a community that, though faded, refuses to be entirely forgotten. The walls may have fallen, but the memory of Jericho, Texas, endures, carried on the ceaseless wind of the Panhandle.