John Brown’s Fort: A Small Stone Building That Ignited a Nation

Nestled at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah Rivers, where the majestic Blue Ridge Mountains converge, lies Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. Today, it’s a picturesque town, a popular tourist destination, and a meticulously preserved National Historical Park. But beneath its tranquil facade lies a turbulent history, a story inextricably linked to a small, unassuming stone structure: John Brown’s Fort. More than just a building, this former fire engine house became the epicenter of an audacious raid in October 1859, a desperate act by a radical abolitionist that failed in its immediate objective but succeeded in igniting the simmering tensions between North and South, pushing a divided nation inexorably towards civil war.

To understand the fort’s profound significance, one must first understand the man who made it famous. John Brown was no ordinary activist. A devout Calvinist with a fierce, Old Testament sense of justice, he believed slavery was a moral abomination that could only be purged with blood. Having witnessed and participated in the brutal "Bleeding Kansas" conflicts, Brown grew convinced that peaceful means had failed. He envisioned a dramatic strike against the institution of slavery, a blow so audacious it would spark a widespread slave insurrection across the South, creating a new, free republic for the enslaved. Harpers Ferry, with its federal arsenal containing thousands of weapons, its strategic location on the border between slave and free states, and its relatively sparse population, seemed the perfect target for his revolutionary scheme.

The Audacious Raid

On the night of Sunday, October 16, 1859, John Brown, leading a small, dedicated band of 21 men – including five Black men and his own sons – launched his fateful attack. Their initial objective was simple: seize the federal arsenal and armory, confiscate the weapons, and distribute them to enslaved people, who Brown believed would flock to his banner. The raid began quietly, with the men cutting telegraph wires and capturing the arsenal’s watchman. They quickly secured the armory and the federal rifle works.

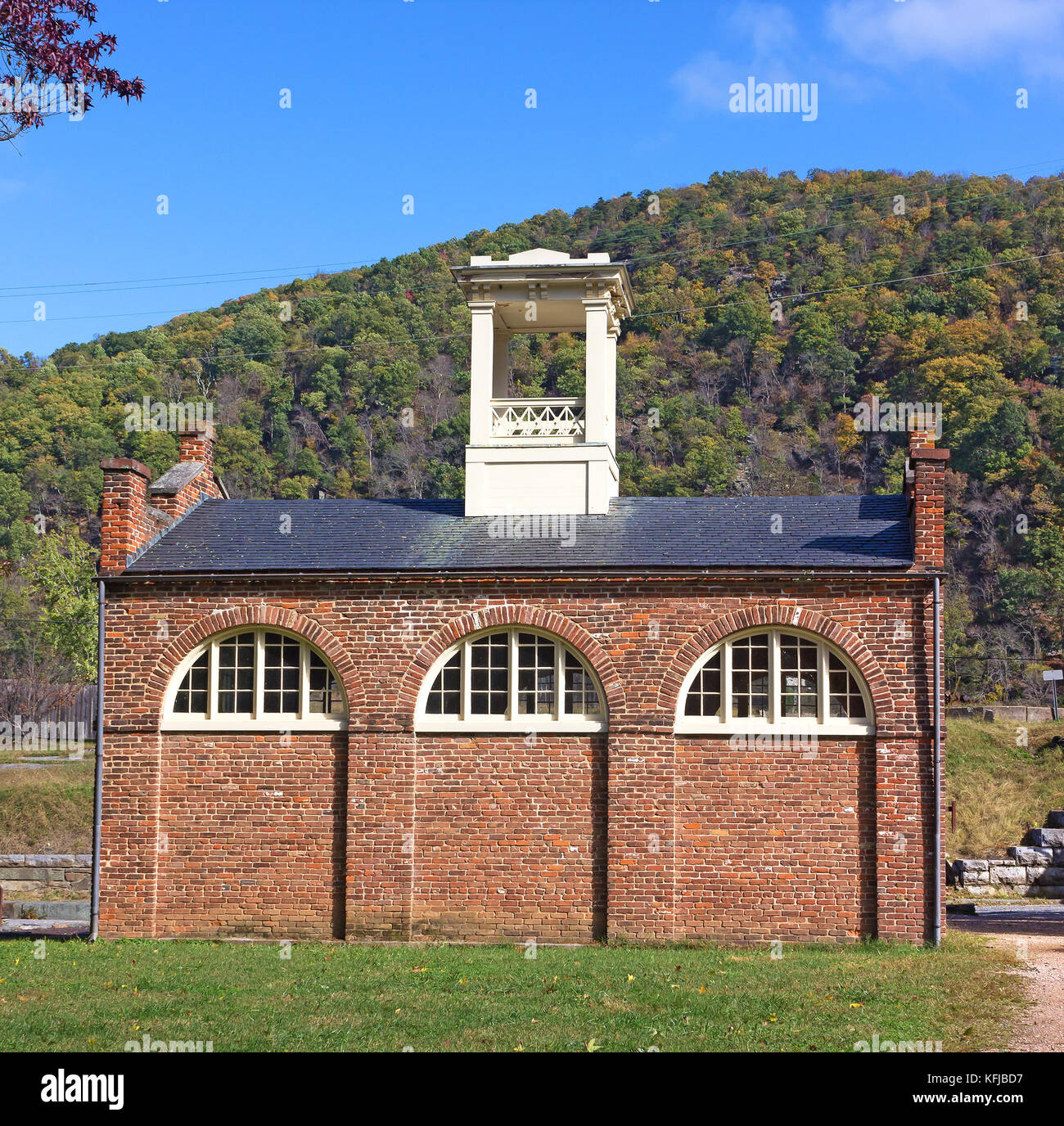

The engine house, a sturdy brick and stone structure designed to house fire engines, became their initial stronghold and headquarters. It was here that Brown and his men held hostages, including Colonel Lewis Washington, a great-grandnephew of George Washington, and the local mayor. The initial hours of the raid were met with little resistance, but this deceptive calm would soon shatter.

"I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood," Brown had written in a prophetic note just before his execution. This sentiment, chilling in its foresight, defined his mission. He was not seeking a negotiated peace; he was seeking a reckoning.

However, Brown’s plan quickly unraveled. The expected uprising of enslaved people never materialized. Word of the raid spread rapidly, not through Brown’s intended channels, but through terrified locals and a crucial, intercepted train. The conductor of a B&O Railroad train, initially held by Brown’s men, was allowed to proceed to the next station, where he telegraphed news of the attack. Local militias, initially disorganized, began to converge on Harpers Ferry, engaging Brown’s men in scattered gunfights. One of the first casualties was Heyward Shepherd, a free Black baggage master, shot by Brown’s men in the chaotic initial hours, a tragic irony that would later be manipulated by Southern sympathizers.

By Monday morning, October 17, the situation for Brown and his raiders had become dire. Trapped in the engine house, surrounded by an increasingly hostile and well-armed local populace, their numbers dwindling, the dream of a mass insurrection evaporated. Brown, surprisingly, seemed to hesitate, missing opportunities to escape into the mountains. Perhaps he truly believed that divine intervention or a surge of support would eventually come.

The Siege and Capture

As the day wore on, the sound of gunfire echoed through the valley. Brown’s men, though outnumbered, fought fiercely from their fortified position. But their fate was sealed when federal troops, dispatched by President James Buchanan, began to arrive. Under the command of Colonel Robert E. Lee, a then-little-known officer of the U.S. Army, and his aide, Lieutenant J.E.B. Stuart, a detachment of U.S. Marines moved in.

By dawn on Tuesday, October 18, the Marines were ready to storm the engine house. Stuart, under a flag of truce, attempted to negotiate Brown’s surrender, but Brown refused. With negotiations failed, Lee gave the order. Marines, armed with sledgehammers and a heavy ladder, battered down the engine house doors. The assault was swift and brutal. Within minutes, the remaining raiders were overwhelmed. Several were killed, others wounded. John Brown himself, severely injured by a bayonet thrust, was captured.

The raid was over. Of Brown’s 22 men (including himself), ten were killed, five escaped, and seven, including Brown, were captured. Five local citizens and one Marine also died during the conflict. The small stone engine house, riddled with bullet holes and stained with blood, stood as a stark testament to the violent clash of ideologies.

Trial, Execution, and the Divided Nation

Brown’s trial in Charles Town, Virginia (now West Virginia), was swift. Charged with treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia, murder, and inciting slave insurrection, he was found guilty on all counts. Throughout the proceedings, Brown maintained a remarkable composure, often appearing more the accuser than the accused. In his famous courtroom speech, delivered after the verdict, he declared, "I believe to have interfered as I have done…in behalf of His despised poor, was not wrong, but right. Now, if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood further with the blood of my children and with the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel, and unjust enactments – I submit; so let it be done!"

His words resonated deeply, particularly in the North, where many abolitionists began to view him as a martyr. Ralph Waldo Emerson called him a "new saint awaiting his martyrdom." Henry David Thoreau hailed him as "an angel of light." Southern states, however, viewed him as a dangerous terrorist, a maniacal zealot who sought to incite racial warfare. They saw his raid as a direct assault on their way of life, a harbinger of Northern aggression.

On December 2, 1859, John Brown was hanged. His execution, witnessed by future Confederate generals Stonewall Jackson and John Wilkes Booth, only deepened the chasm between North and South. The raid, and Brown’s subsequent trial and execution, became a flashpoint, a powerful symbol that crystallized the irreconcilable differences over slavery. It demonstrated that compromise was no longer possible, and that the "bloody purge" Brown foresaw was indeed on the horizon. The Civil War would begin less than two years later.

The Wandering Fort: A Journey Through Time

The story of John Brown’s Fort doesn’t end with his execution. The small building itself embarked on a remarkable journey, a testament to its enduring symbolic power. After the raid, it remained at Harpers Ferry, witnessing the town change hands eight times during the Civil War, often serving as a prison or storage facility. Its significance, however, was not forgotten.

In 1891, the fort made its first major move. Local residents, recognizing its historical value, had it dismantled stone by stone and shipped to Chicago to be exhibited at the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893. The idea was to highlight the site’s importance in the national narrative. This initial relocation, though controversial, ensured its preservation.

After the Exposition, the fort faced an uncertain future. Fortunately, it found a new home in 1895 at Storer College, a historically Black institution founded in Harpers Ferry after the Civil War to educate formerly enslaved people. This move was particularly poignant, placing the fort on the grounds of a school dedicated to the very people Brown had sought to liberate. It stood as a powerful symbol of progress and the ongoing struggle for civil rights, hosting gatherings and speeches by prominent figures like Frederick Douglass and W.E.B. Du Bois.

However, Storer College eventually faced financial difficulties and closed its doors in 1955. The fort, once again, was in need of a home. In 1909, on the 50th anniversary of the raid, it was acquired by the federal government and moved a final time, a short distance to its current location within what is now Harpers Ferry National Historical Park. While not on its exact original foundation (which is marked nearby), it stands as close as possible, providing visitors with a tangible link to that pivotal moment in American history.

Legacy and Interpretation

Today, John Brown’s Fort remains one of the most visited sites in Harpers Ferry National Historical Park. It stands as a silent sentinel, a small building that holds immense historical weight. Its presence continues to provoke questions and debates: Was John Brown a righteous martyr or a deluded terrorist? A visionary or a madman? A freedom fighter or a domestic insurgent? The answer, perhaps, lies in the eye of the beholder, shaped by one’s own values and historical perspective.

The National Park Service, in its role as interpreter of history, presents the fort not as a monument to one man’s ideology, but as a catalyst, a physical manifestation of the deep-seated conflicts that tore the nation apart. It forces visitors to confront uncomfortable truths about slavery, abolitionism, and the violent path to freedom.

Standing before its weathered stone walls, one can almost hear the echoes of gunfire, the shouts of men, and the desperate pleas of hostages. One can imagine John Brown, wounded but unbowed, refusing to surrender, convinced of the righteousness of his cause. The fort is a tangible reminder that history is not always neat or easily categorized, and that profound social change often comes at a terrible cost.

John Brown’s Fort is more than just an old building; it is a powerful symbol of courage, conviction, and controversy. It reminds us of the moral imperatives that can drive individuals to extreme acts, and the profound, often unintended, consequences that can ripple through generations. It is a place where the past actively engages with the present, prompting reflection on justice, freedom, and the enduring struggle for human rights in America and beyond. It is a small stone building that, in its journey and its story, continues to speak volumes about the soul of a nation.