John Doyle Lee: Scapegoat, Fanatic, and the Enduring Stain of Mountain Meadows

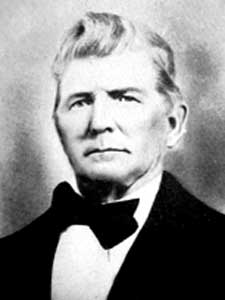

The wind whipped across the barren plains of Mountain Meadows on March 23, 1877, carrying the chill of the Utah spring and the heavy weight of history. A lone figure, John Doyle Lee, stood before a firing squad, not far from the site where two decades prior, an unimaginable horror had unfolded. Convicted of his role in the massacre of some 120 Arkansas emigrants, Lee, a once-loyal pillar of the Mormon community and an adopted son of Brigham Young, faced his final reckoning. His last words, delivered with a mixture of defiance and self-pity, would forever echo the controversy surrounding his life and death: "I am ready to die. I have no fear. I have done nothing criminal."

Yet, the historical record, his own confessions, and the verdict of two trials paint a far more complex and damning picture. Lee was indeed a central figure in one of the most infamous atrocities on American soil, a dark chapter that continues to haunt the historical narrative of the American West and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Was he a cold-blooded killer, a fanatic blinded by faith, or a convenient scapegoat for a wider conspiracy? John Doyle Lee’s story is a chilling exploration of loyalty, betrayal, and the destructive power of collective delusion.

The Ascendant Pioneer: Loyalty and the Lure of Zion

Born in Kaskaskia, Illinois, in 1812, John Doyle Lee’s early life was unremarkable until his conversion to Mormonism in 1838. Like thousands of others, he was drawn to the nascent faith’s promise of a restored gospel and a new Zion. Lee quickly proved to be an exceptionally devoted and energetic convert. He participated in the church’s early struggles, including the expulsion from Missouri and Illinois, and joined the arduous trek west to the Salt Lake Valley.

His unwavering loyalty and industrious nature did not go unnoticed by the church’s charismatic leader, Brigham Young. Lee became one of Young’s "adopted sons" – a spiritual, though not biological, relationship that signified immense trust and influence within the tightly-knit community. He embraced polygamy, marrying multiple wives, a practice central to the early Mormon faith and a symbol of his commitment. He served as a bishop, a probate judge, and an Indian agent, roles that granted him significant authority in the isolated Iron County, a remote outpost in southern Utah. He was instrumental in establishing settlements, building infrastructure, and cultivating relationships (and sometimes tensions) with the local Paiute tribes.

This was a man who had dedicated his life, his family, and his fortune to the cause of his faith. He believed implicitly in the divine mission of Brigham Young and the righteousness of the Mormon people. However, this fervent devotion, coupled with the unique socio-political climate of Utah in the 1850s, would create the perfect storm for tragedy.

The Seeds of Tragedy: Paranoia and the "Blood Atonement"

By 1857, the isolated Mormon settlements in Utah were simmering with paranoia and resentment. The "Utah War" had begun, as President James Buchanan dispatched federal troops to the territory, ostensibly to replace Brigham Young as governor. To the Latter-day Saints, who had endured years of persecution and violence, this was another attempt to crush their faith and seize their hard-won sanctuary. Brigham Young declared martial law, calling for a total boycott of federal authority and preparing for what many believed would be a final, existential conflict.

Adding to the tension was the "Mormon Reformation" of 1856-57, a period of intense spiritual re-dedication preached by church leaders. Rhetoric during this time was fiery, emphasizing absolute obedience, the need for personal purity, and a controversial doctrine known as "blood atonement." This doctrine, interpreted by some to mean that certain sins were so grievous they could only be atoned for by shedding the sinner’s own blood, fueled a climate of fear and righteous indignation against "Gentiles" (non-Mormons) and apostates. Sermons from leaders, including Brigham Young and George A. Smith, spoke of enemies within and without, painting a stark picture of a beleaguered people ready to defend their Zion at all costs.

It was into this volatile atmosphere that the Fancher-Baker party, a wagon train of some 120 emigrants from Arkansas and Missouri, entered Utah. Bound for California, they were a diverse group of families, many with children, seeking new opportunities. Rumors preceded them, amplified by the pervasive paranoia: they were said to be hostile, desecrating Mormon sacred sites, poisoning wells, and boasting of past participation in anti-Mormon violence in Missouri. While these rumors were largely unfounded, in the heightened state of alert, they were readily believed and dangerously amplified.

The Massacre: Betrayal at Mountain Meadows

The Fancher-Baker party arrived at Mountain Meadows, a lush, well-watered valley in southern Utah, in early September 1857. They were immediately surrounded by a combined force of local Mormon militiamen, dressed as Native Americans, and Paiute warriors. John D. Lee, as the local Indian agent and a major in the Iron County Militia, was deeply involved from the outset.

For five days, the emigrants were besieged, their supplies dwindling, their hope fading. Several were killed in initial skirmishes. The militiamen, under the command of Isaac Haight and William H. Dame, held councils to determine the party’s fate. Accounts suggest a desperate attempt by some to spare the emigrants, but ultimately, the decision was made to eliminate them. The fear was that if the emigrants were allowed to pass through, they would report the Mormon aggression to federal troops. The cover-up, it was decided, required no survivors.

Lee was chosen to negotiate with the trapped emigrants. On September 11, under a flag of truce, he approached the wagon train, promising safe passage and protection from the Paiutes if they surrendered their weapons. The desperate emigrants, trusting the white man’s word, agreed. They were led out of their encampment, the men separated from the women and children.

What followed was an act of unfathomable betrayal and brutality. At a prearranged signal, the militiamen and Paiute warriors turned on the unarmed emigrants. The men were shot at close range; the women and older children were bludgeoned and stabbed to death. Only 17 children, deemed too young to report the events, were spared and taken in by local Mormon families. Lee himself later confessed to participating directly in the killings, leading a group that executed the men, and described the horrific scene in vivid detail. His account, given in his own confession, chillingly describes the systematic slaughter.

Years of Fugitive and Betrayal

In the immediate aftermath, a desperate attempt was made to conceal the massacre. The bodies were hastily buried, and the militiamen were sworn to secrecy. Brigham Young, upon hearing the news, reportedly ordered the children to be cared for but also instructed that the event be blamed entirely on the Paiute Indians. For years, this remained the official narrative.

However, the sheer scale of the atrocity and the presence of white men at the scene made a complete cover-up impossible. Federal investigations began, slowly and sporadically, hampered by the isolation of Utah and the unified silence of the Mormon community. John D. Lee, the most prominent figure present at the massacre and the one most deeply implicated, became a marked man.

He spent years living as a fugitive, often under assumed names, moving from one remote settlement to another. He operated ferries, ran ranches, and tried to evade the increasingly insistent reach of federal law. As political winds shifted and federal pressure on the Mormon Church intensified, particularly regarding polygamy, the church found itself in a precarious position. The Mountain Meadows Massacre remained a persistent stain, and the federal government was determined to find someone to hold accountable.

The Trials and Condemnation

In 1874, John D. Lee was finally apprehended. His arrest marked a turning point in the quest for justice. His first trial, in 1875, resulted in a hung jury. The defense argued that Lee was merely following orders and that others were equally, if not more, culpable. Indeed, many others had participated, but the prosecution struggled to secure convictions against anyone else, largely due to a lack of willing witnesses and the difficulty of prosecuting an entire community.

The second trial, in 1876, was different. The prosecution, acutely aware of the need for a conviction, focused solely on Lee. The political climate had shifted dramatically. Brigham Young and other church leaders, while not directly testifying against Lee, offered no support. Lee, by then excommunicated from the church, was effectively abandoned. He became the designated scapegoat, the one man who would pay for the sins of many.

His defense was largely centered on the idea that he was a pawn in a larger game, forced by fear and obedience to participate. He claimed he was merely carrying out the orders of his ecclesiastical superiors, particularly Isaac Haight and William H. Dame. While this did not absolve him of his direct actions, it highlighted the collective responsibility that many historians still debate. The jury, however, found him guilty of murder in the first degree.

The Final Reckoning and Enduring Legacy

On March 23, 1877, John D. Lee was brought back to Mountain Meadows for his execution. It was a deliberate choice of location, a stark symbol of justice being served where the crime was committed. He was allowed to choose his method of execution, opting for a firing squad.

Before the rifles fired, Lee delivered a lengthy, defiant speech, reiterating his belief that he was a victim of circumstance and betrayal. He acknowledged his role but continued to shift blame to those above him, accusing Brigham Young and other leaders of deserting him. "I am a Mormon, and I believe in the Mormon religion," he declared. "I am a true believer in the gospel of Jesus Christ. I have no fear of death. I am ready to die." He maintained his innocence of malice, portraying himself as a man caught in an impossible situation. With a final prayer, he sat on his coffin, facing his executioners. The shots rang out, and John D. Lee’s life ended, bringing a measure of closure to a national tragedy.

John Doyle Lee’s legacy is a complex and tragic one. For many, he remains the face of the Mountain Meadows Massacre, a symbol of the dangers of fanaticism and unchecked authority. His name is synonymous with the horrific betrayal that occurred that September day. For others, particularly within historical interpretations that seek to understand the broader context, he is seen as a scapegoat, a man who, while undeniably culpable, paid the ultimate price for the actions and decisions of a wider group and a church leadership that ultimately distanced itself from him.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has, over time, moved towards greater transparency regarding the massacre, acknowledging the involvement of its members and condemning the actions. Monuments stand at Mountain Meadows today, commemorating the victims and serving as a stark reminder of the tragedy. John Doyle Lee’s life, from his zealous conversion to his ignominious death, serves as a powerful cautionary tale about the corrosive effects of fear, the manipulation of faith, and the enduring human quest for justice, even when that justice is imperfect and shadowed by the complexities of history. His story ensures that the stain of Mountain Meadows will never truly fade.