Echoes of Dispossession: Kahnawà:ke’s Enduring Struggle for Land and Sovereignty

Kahnawà:ke, Quebec – Beneath the shadow of Montreal’s sprawling urban landscape, where the mighty St. Lawrence River flows, lies the Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) community of Kahnawà:ke. For centuries, this vibrant nation has asserted its inherent rights to a vast ancestral territory, a claim that predates the very foundations of Canada and remains a persistent, often contentious, issue at the heart of reconciliation efforts. It is a struggle not merely for tracts of land, but for identity, sovereignty, and the rectification of historical injustices that have echoed through generations.

The Kahnawà:ke Mohawk land claims are complex, rooted in colonial-era land grants, broken promises, and a deep spiritual connection to the earth that contrasts sharply with Western concepts of property ownership. At the core of their grievances is the shrinking of their traditional lands, known as Kaniatarowanenneh, which once encompassed a significant portion of what is now southern Quebec and parts of New York State.

"For generations, our elders have spoken of the land that was taken," says Ohén:ton Í:wa, a respected community elder, her voice carrying the weight of history. "It’s not just dirt; it’s our identity, our history, our future. Every tree, every rock, every river holds the stories of our ancestors."

A History of Diminishment

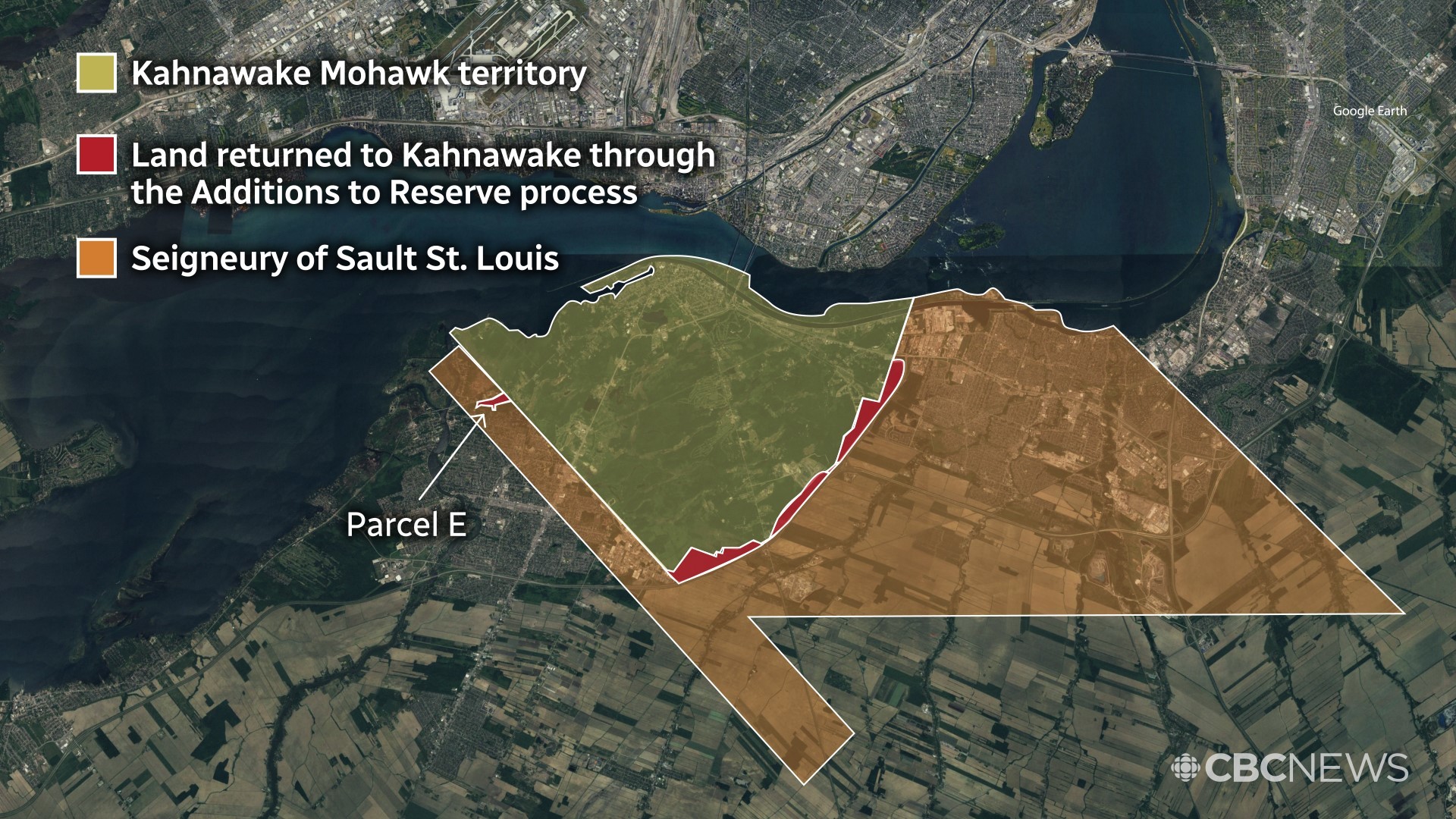

The roots of the current claims stretch back to the 17th century. The Mohawks, one of the original five nations of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy, were powerful and influential. In 1680, the French Crown, through the Jesuits, granted the Mohawks a seigniory known as Sault St. Louis (now Kahnawà:ke) to establish a mission and a settlement. This grant, however, was not a transfer of ownership as understood by Europeans, but rather a recognition of the Mohawks’ inherent right to occupy and use the land. Crucially, the Mohawks believed this grant was intended to be held in common for their perpetual use and benefit.

Over time, this understanding was eroded. Successive colonial powers—French and then British—began to carve up and sell off portions of the seigniory without the consent of the Mohawk people. By the 19th century, the vast tract of land originally understood to be theirs had been significantly reduced, parcelled out to non-Indigenous settlers and businesses.

One pivotal moment often cited by Kahnawà:ke is a purported "deed of surrender" in 1793, which supposedly extinguished their title to much of the seigniory. The Mohawks vehemently dispute the validity of this document, arguing it was never properly understood or consented to by the community, and that it was executed under duress or misunderstanding. They maintain their inherent title was never extinguished.

"The concept of ‘surrender’ is a colonial invention," states Kahionhes Akwiranó:ron, a legal scholar specializing in Indigenous law. "Our people never ‘surrendered’ their land. They shared it, they used it, but they never gave up their inherent rights to it. The 1793 document is a perfect example of how colonial powers manipulated legal frameworks to dispossess Indigenous nations."

The Oka Crisis and its Resonance

While the Kahnawà:ke land claims are distinct, they are inextricably linked in the public consciousness with the Oka Crisis of 1990. Though the standoff over a golf course expansion occurred primarily in the neighbouring Mohawk community of Kanesatake, Kahnawà:ke played a crucial solidarity role that brought their own land grievances into sharp focus.

When Canadian forces and Quebec police surrounded Kanesatake, Kahnawà:ke Mohawks responded by blockading the Mercier Bridge, a vital artery connecting Montreal to its South Shore suburbs. This act of defiance, which lasted for weeks, paralyzed traffic and brought the issue of Indigenous land rights directly into the daily lives of millions of Quebecers. The blockade was a direct expression of their own frustration with unaddressed land claims and a powerful show of solidarity for their Kanesatake kin.

"Oka was a wake-up call, not just for Canada, but for our own people," recalls Tekaronhió:ken, a community member who participated in the Mercier Bridge blockade. "It showed the world how far we would go to protect what is ours, and it forced people to look at the history of injustice. Our claims might be different from Kanesatake’s, but the spirit behind them is the same: this land is ours, and we will defend it."

The Oka Crisis, though decades ago, continues to shape the dialogue around Indigenous land rights in Canada, serving as a stark reminder of the potential for conflict when these issues remain unresolved.

The Nature of the Claim: More Than Just Acres

Today, the Mohawk Council of Kahnawà:ke (MCK) continues to pursue its land claims through various avenues, primarily focusing on the "Common Seigniory" claim. This claim asserts that the entire original seigniory of Sault St. Louis, which covered an area far larger than the current reserve, belongs to the Kahnawà:ke Mohawks due to the invalidity of the 1793 surrender and subsequent illegal dispositions of the land.

The claims are not simply about monetary compensation, although that is often part of the negotiation process. They are fundamentally about the recognition of Indigenous title, the restoration of traditional governance, and the ability to exercise self-determination over their ancestral lands.

"We’re not just looking for a cheque," asserts Iakowennahó:te, a spokesperson for the Mohawk Council of Kahnawà:ke. "We’re looking for justice. We want our land back, not necessarily every single square inch of it, but the recognition that it was taken from us unjustly, and that we have a right to our traditional territory and all the benefits that flow from that. It’s about nation-to-nation relations, about our inherent sovereignty."

The Kahnawà:ke Mohawks argue that their land claims fall under the "specific claims" process, which addresses past grievances arising from the breach of lawful obligations by the Crown. This process, often lengthy and arduous, can involve negotiations, mediation, or adjudication through the Specific Claims Tribunal of Canada.

Challenges and the Path Forward

Despite the clear historical record and the urgency expressed by the Kahnawà:ke community, progress on land claims has been painstakingly slow. Bureaucracy, shifting government priorities, and a fundamental disagreement over the interpretation of historical events often bog down negotiations.

One of the significant challenges lies in the concept of "unceded territory." Unlike many First Nations in Canada who have signed treaties that define their land base, the Mohawks of Kahnawà:ke maintain that their lands were never ceded through a legitimate treaty process. This distinction places their claims in a unique legal and historical context, often requiring a more fundamental rethinking of colonial land ownership.

Furthermore, the expansion of Montreal and surrounding municipalities continually encroaches upon the historical territory, leading to conflicts over infrastructure projects, housing developments, and resource extraction. The ongoing construction of Highway 30, for instance, has been a source of tension, with Kahnawà:ke asserting its right to be consulted and to benefit from developments on its traditional lands.

Internal dynamics within Kahnawà:ke also add layers of complexity. While there is a strong consensus on the importance of land claims, discussions around membership, the rights of non-Indigenous residents within the reserve, and economic development can sometimes create internal divisions, though these are often secondary to the overarching goal of reclaiming what was lost.

The path forward for Kahnawà:ke’s land claims is unlikely to be straightforward. It will require continued advocacy, legal battles, and a willingness from all levels of government—federal, provincial, and municipal—to engage in genuine, nation-to-nation dialogue based on respect and reconciliation.

"Our struggle for land is intertwined with our struggle for self-determination," says Ohén:ton Í:wa, reflecting on the long journey ahead. "We are the Kanien’kehá:ka, the People of the Flint. We have endured for centuries, and we will continue to assert our rights. The land remembers, and so do we."

The Kahnawà:ke Mohawk land claims stand as a potent symbol of the unfinished business of reconciliation in Canada. They remind us that history is not a static past but a living force, shaping the present and demanding justice for the future, one ancestral territory at a time. The echoes of dispossession are loud, and Kahnawà:ke continues to demand that Canada listen.