Echoes on Paper: The Enduring Legacy of Kiowa Ledger Art

More than mere accounting records, the worn pages of 19th-century ledger books, once symbols of colonial imposition, became canvases for a profound artistic and historical expression among the Kiowa people. Transformed by the hands of warriors and artists, these commercial ledgers, government documents, and even Bible pages became the unlikely repositories of a vibrant visual history – a practice now known as Kiowa ledger art. This unique art form, born from a period of immense upheaval and cultural suppression, stands as a testament to the Kiowa’s resilience, their unwavering commitment to their heritage, and their ingenious adaptation in the face of radical change.

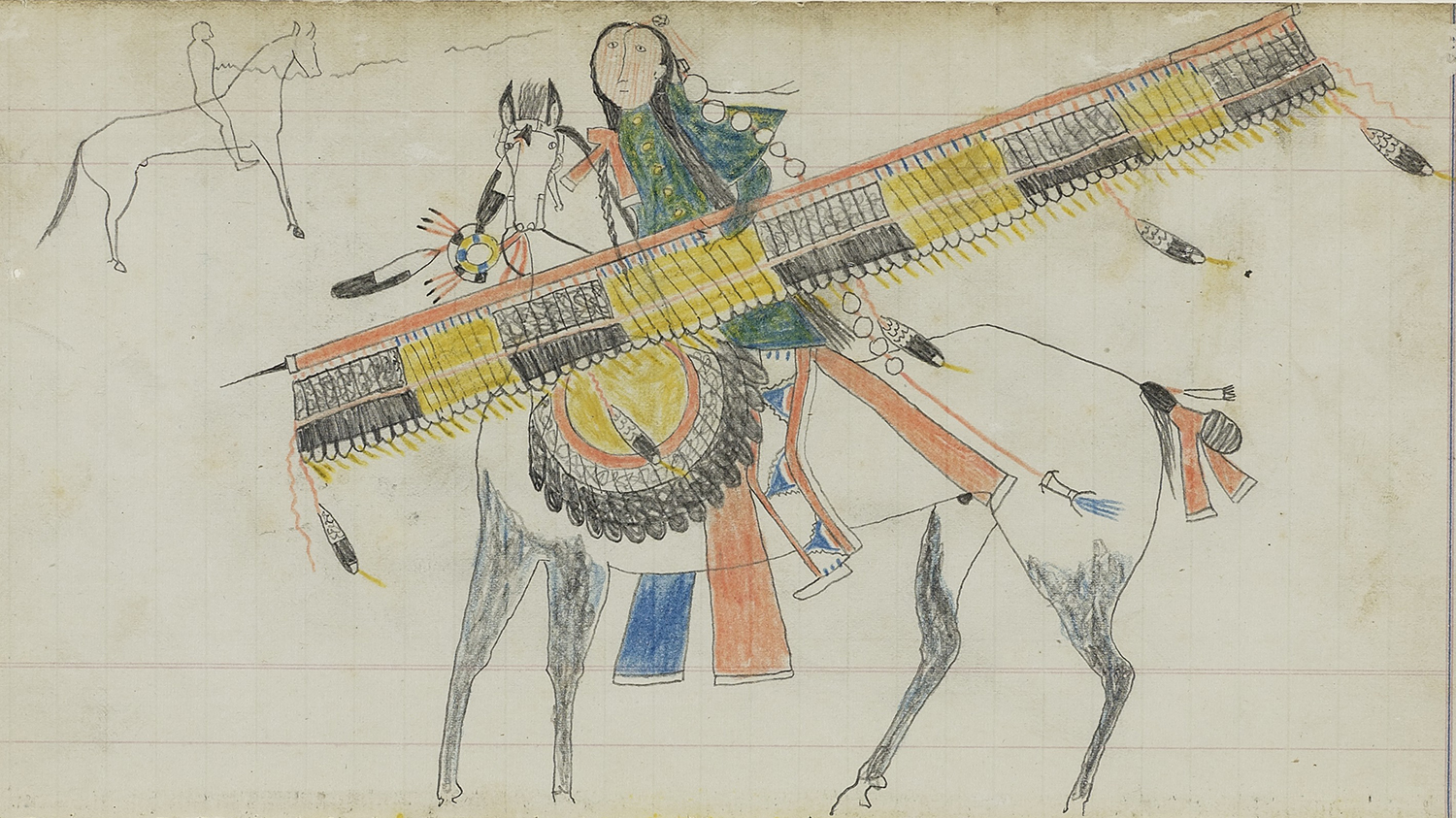

To understand Kiowa ledger art, one must first grasp the historical crucible from which it emerged. For centuries, the Kiowa were a powerful nomadic Plains tribe, their lives intricately woven with the buffalo, their spiritual beliefs tied to the vast open landscapes, and their social structures defined by equestrian prowess and warrior societies. Their artistic traditions, primarily hide painting, celebrated war deeds, spiritual visions, and communal life, serving as a visual archive passed down through generations.

However, the late 19th century brought an abrupt and brutal end to this way of life. The relentless westward expansion of the United States, the systematic slaughter of the buffalo, and a series of broken treaties culminated in the forced confinement of the Kiowa and other Plains tribes onto reservations. The Battle of Adobe Walls (1874) and the subsequent Red River War marked the final military defeat for many Southern Plains tribes, including the Kiowa. Stripped of their lands, their primary food source, and their freedom to roam, the Kiowa faced an existential crisis.

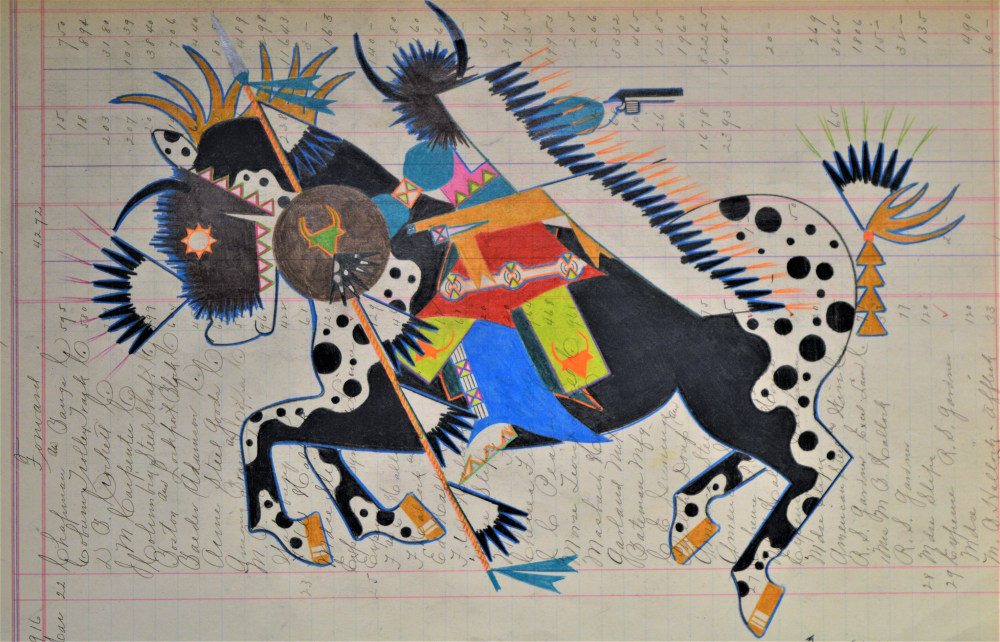

It was within this context of profound cultural disruption, often during periods of imprisonment such as at Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida, that ledger art began to flourish. Traditional materials like buffalo hides became scarce or unobtainable. Yet, the innate human need to record, to remember, and to express persisted. When paper, pencils, crayons, and watercolors became available – often through missionaries, agents, or even as discarded administrative materials – Kiowa artists seized upon these new mediums. The transition was not merely one of medium but also of opportunity: the small, portable nature of the ledger book allowed for a more intimate and personal form of expression, often created in secret or in confined spaces.

A Visual Diary of a Vanishing World

Kiowa ledger art served multiple crucial purposes. Firstly, it was a vital historical record. The artists, many of whom were warriors or highly respected individuals, meticulously documented their past lives: daring war exploits, successful buffalo hunts, elaborate ceremonial dances like the Sun Dance, social gatherings, and intimate portraits of individuals in traditional regalia. These drawings were not just pretty pictures; they were visual narratives, often read from left to right like a book, detailing specific events, identifying participants, and preserving the memory of a way of life that was rapidly disappearing.

Secondly, ledger art was a form of cultural assertion and resistance. In an era when government policies actively sought to eradicate Native languages, religions, and traditions, the act of drawing these scenes was a defiant affirmation of identity. It was a silent, yet powerful, declaration: "We remember who we are. We remember what we did. We remember our power and our beauty." The very act of transforming a symbol of colonial bureaucracy (the ledger book) into a repository of Indigenous history was a subversive act of reclamation.

Thirdly, for the artists themselves, it was a coping mechanism. The trauma of forced assimilation, the loss of loved ones, and the profound grief over a vanished way of life could be channeled into artistic creation. It provided an outlet for memory, a connection to the past, and a means to process their experiences. It allowed them to relive glorious moments, mourn their losses, and envision a future where their culture might survive.

Artistic Style and Notable Artists

Kiowa ledger art, while utilizing new materials, retained many stylistic conventions from traditional hide painting. Figures are often depicted in profile or three-quarter view, with a strong emphasis on detail in clothing, weaponry, and regalia. Perspective is typically flat, and the background is often minimal, directing the viewer’s attention to the dynamic action of the figures. Colors, though limited by available materials (often commercial crayons or watercolors), are vibrant and used expressively. The narratives are clear and concise, focusing on the essential elements of the story.

Several Kiowa artists became prominent figures in the ledger art tradition, leaving behind an invaluable body of work:

-

Wohaw (c. 1855–1924): One of the most famous ledger artists, Wohaw was among the 72 Plains warriors imprisoned at Fort Marion. His drawings from this period are particularly poignant, often depicting the stark contrast between his traditional life and the realities of confinement. His iconic piece, "Between Two Worlds" (c. 1878), vividly illustrates his internal conflict, showing him caught between the buffalo and tipi of his past and the steer and house of his enforced present, with a cornstalk growing from his heart. Wohaw’s work is celebrated for its emotional depth and its unique ability to convey the complexities of cultural transition.

-

Silver Horn (Hohaw) (c. 1860–1940): A prolific and highly influential artist, Silver Horn was a Kiowa medicine man and a master of both traditional and ledger art. His oeuvre is vast, encompassing a wide range of subjects from war scenes and ceremonial dances to detailed depictions of daily life, hunting, and even mythological figures. His artistic output spanned several decades, and his intricate details, dynamic compositions, and rich storytelling made him one of the most significant figures in Kiowa art. He also experimented with new techniques and subjects, demonstrating the evolving nature of the art form.

-

Koba (c. 1859–1881): Another Fort Marion artist, Koba’s work is characterized by its meticulous detail and focus on narrative. He often depicted war scenes, counting coup, and horse raids, showcasing the bravery and skill of Kiowa warriors. His drawings offer valuable insights into Kiowa military practices and social structures.

-

Zotom (c. 1853–1918): Also a Fort Marion prisoner, Zotom’s art is notable for its vibrant use of color and its energetic portrayal of ceremonies and social gatherings. His work often conveys a sense of movement and celebration, even amidst the grim realities of imprisonment.

The Narrative Power and Enduring Legacy

Each ledger drawing is a compact narrative, a single frame in a longer saga. The viewer is invited to piece together the story, interpreting the actions, identifying the individuals by their distinctive clothing or markings, and understanding the cultural significance of the depicted events. This narrative power is central to the art form’s appeal and its historical value. They are not merely static images but dynamic visual accounts, speaking across time.

Kiowa ledger art is more than just an historical curiosity; it is an act of profound cultural resilience. It demonstrated the Kiowa people’s ability to adapt, innovate, and preserve their identity even under extreme duress. It provided a bridge between the old ways and the new realities, ensuring that the knowledge, values, and histories of the Kiowa people would not be lost.

Today, the legacy of Kiowa ledger art continues to resonate. Contemporary Native American artists draw inspiration from its techniques, themes, and spirit of cultural affirmation. Modern ledger artists, both Kiowa and from other Plains tribes, use the form to explore contemporary issues, reflect on historical trauma, celebrate modern identity, and continue the tradition of visual storytelling. The art has also gained significant recognition in mainstream art institutions, with major museums acquiring and exhibiting these vital historical and artistic treasures.

In conclusion, the pages of Kiowa ledger art are not just paper and pigment; they are living documents, pulsating with the memories, struggles, and triumphs of a people who refused to be erased. They stand as a powerful reminder that art can be a potent tool for survival, a defiant act of memory, and a timeless testament to the enduring spirit of a culture. Through these vibrant drawings, the thunder of the buffalo, the bravery of warriors, and the beauty of Kiowa ceremonies continue to echo, forever etched on the repurposed pages of history.