Echoes of the Sacred: The Enduring Spiritual Heart of the Lakota Sioux

The vast, rolling plains of North America, where the wind whispers through the grasses and the sky stretches endlessly, have for millennia been the sacred canvas for the Lakota Sioux. More than just a people, they are a living testament to a profound spiritual heritage, one deeply intertwined with the land, the cosmos, and every living thing. Their spiritual practices are not merely rituals but the very fabric of their existence, a worldview that has endured centuries of immense challenge, suppression, and misunderstanding.

To understand Lakota spirituality is to grasp the concept of Wakan Tanka, the Great Mystery. This is not a singular, anthropomorphic deity in the Western sense, but rather the pervasive, interconnected essence of all creation. It is the sacredness inherent in every rock, tree, animal, and human being. From this fundamental understanding flows the core Lakota philosophy: Mitakuye Oyasin – All My Relations. This phrase, often translated simply as "we are all related," encompasses a far deeper meaning. It signifies a profound awareness of the interconnectedness of all life – human, animal, plant, mineral, and even the elements – recognizing a shared kinship and a collective responsibility to maintain harmony and balance within the sacred hoop of life.

As the renowned Oglala Lakota holy man Black Elk famously articulated, "The first peace, which is the most important, is that which comes within the souls of men when they realize their relationship, their oneness with the universe and all its powers, and when they realize that at the center of the universe dwells Wakan-Tanka, and that this center is really everywhere, it is within each of us." This encapsulates the holistic nature of Lakota spirituality, where personal well-being is inseparable from the well-being of the entire creation.

The Sacred Pipe: A Breath of Prayer

Central to nearly all Lakota ceremonies is the Chanunpa, the Sacred Pipe. More than just an object, it is considered a living entity, a conduit between the human world and the spiritual realm. Its origin story tells of the White Buffalo Calf Woman, a sacred being who appeared to two Lakota hunters in a time of great hunger and strife. She taught them the seven sacred rites and presented them with the Chanunpa, instructing them on its proper use for prayer, healing, and fostering peace.

When the pipe is smoked, the tobacco, a sacred plant, is not inhaled for pleasure but offered as a prayer. Each puff carries intentions, gratitude, and supplications upwards, creating a tangible connection to Wakan Tanka. The pipe ceremony is a solemn and profound act, binding individuals, families, and communities together in shared purpose and devotion. It is used to seal agreements, offer thanks, seek guidance, and purify intentions, making it the heartbeat of Lakota spiritual life.

Inipi: The Sweat Lodge as a Womb of Renewal

One of the most widely practiced and accessible Lakota ceremonies is the Inipi, or Sweat Lodge. Built from natural materials – willow saplings bent into a dome shape and covered with blankets or tarps to create darkness – the lodge represents the womb of Mother Earth. Participants crawl in, sitting in a circle around a pit where super-heated stones, known as "Grandfathers," are placed. Water is poured over the stones, creating steam that fills the lodge, cleansing the body, mind, and spirit.

The Inipi is a powerful experience of purification, prayer, and introspection. Each "door" or round of the ceremony focuses on different prayers – for healing, for family, for the people, for the world. The intense heat, darkness, and shared prayers foster a deep sense of vulnerability, humility, and communion. It is a space for individuals to shed their burdens, connect with their inner selves, and emerge renewed and revitalized, prepared to walk the Red Road – the path of spiritual living.

Hanbleceya: The Vision Quest for Guidance

For those seeking profound personal guidance and connection, the Hanbleceya, or Vision Quest, is a transformative rite. Typically undertaken by young men and women transitioning into adulthood, but also by adults seeking direction or healing, it involves isolating oneself for several days and nights in a remote, sacred location. The individual, often without food or water, prays and fasts, waiting for a vision or a message from the spirit world.

The Hanbleceya is an act of profound humility and courage, a direct confrontation with the self and the vastness of the universe. It is not about demanding a vision but opening oneself to receive one, a sign or message that will guide their life path, reveal their purpose, or offer solutions to personal or communal challenges. The insights gained from a Vision Quest are deeply personal and are often shared only with a trusted spiritual leader who can help interpret their meaning.

Wi-wanyang-wa-c’i: The Sun Dance of Sacrifice and Renewal

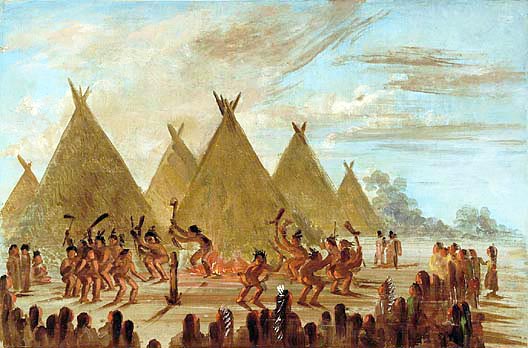

Perhaps the most misunderstood and historically sensationalized Lakota ceremony is the Wi-wanyang-wa-c’i, the Sun Dance. For many, images of "self-torture" or "barbaric rituals" persist, fueled by sensationalist accounts from the 19th and early 20th centuries. In reality, the Sun Dance is the most sacred and profound of Lakota ceremonies, a powerful act of sacrifice, prayer, and communal renewal for the well-being of the entire nation and all creation.

Historically, the Sun Dance was a gathering of entire bands, lasting for several days during the summer solstice. Its central act involves male dancers (and more recently, female dancers in some traditions) making personal vows, often for healing a loved one, for the prosperity of the people, or in gratitude for a prayer answered. As part of their vow, participants may offer a "flesh offering" – a small piece of skin from their chest or back, pierced and attached to the central pole of the Sun Dance arbor by rawhide thongs. The dancers lean back, dancing and praying for hours, until the skin tears free.

This act of piercing is not about pain for pain’s sake, but about extreme sacrifice and offering. It is a tangible demonstration of commitment, a direct offering of oneself to Wakan Tanka on behalf of the people. It is a profound prayer for life, renewal, and the flourishing of the community, mirroring the sacrifices made by the Sun (Wi) to sustain life on Earth. The Sun Dance was outlawed by the U.S. government for many decades, considered "barbaric" by colonial authorities, and its practice went underground until the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978 finally protected Indigenous spiritual practices. Its resurgence today is a powerful symbol of Lakota resilience and the enduring strength of their spiritual path.

Spiritual Leadership and Other Sacred Ways

Lakota spiritual life is guided by Wicasa Wakan (Holy Men) and Winuyan Wakan (Holy Women), often referred to as Medicine People. These individuals undergo years of rigorous training, purification, and spiritual development, learning ancient songs, prayers, and healing practices. They serve as conduits for spiritual wisdom, healers, interpreters of dreams and visions, and keepers of sacred knowledge.

Beyond these major ceremonies, Lakota spirituality is woven into daily life. Naming ceremonies honor new life and give individuals their spiritual names. Healing ceremonies address physical, emotional, and spiritual ailments. The sacred number four, representing the four directions, the four seasons, and the four stages of life, is pervasive. The circular form, seen in the tipis, the Sun Dance arbor, and the sacred hoop, symbolizes unity and the cycles of life.

Challenges and the Path of Resilience

The history of the Lakota people is marked by profound trauma – forced removal from ancestral lands, the decimation of the buffalo, the massacre at Wounded Knee, and the systematic suppression of their culture and spiritual practices through boarding schools and government policies. Children were forbidden to speak their language, practice their ceremonies, or even wear their hair long.

Yet, despite these devastating attempts at assimilation, Lakota spirituality has endured. It survived underground, passed down in secret, whispered from elder to child. The revitalization movements of the late 20th and 21st centuries, fueled by figures like Russell Means and the American Indian Movement, brought many of these practices back into the open. Today, the Inipi, Sun Dance, and Pipe ceremonies are openly practiced on reservations and in urban centers, serving as vital anchors for identity, healing, and cultural continuity.

However, new challenges persist. Cultural appropriation, where non-Native individuals adopt or commercialize Native spiritual practices without understanding or respect, remains a concern. Poverty, addiction, and historical trauma continue to plague many Lakota communities, yet it is often through the resurgence of traditional spiritual practices that individuals and communities find strength, hope, and a path to healing.

The Lakota Sioux spiritual practices are not relics of the past; they are living, breathing traditions that offer profound wisdom for the modern world. They remind us of our intrinsic connection to nature, the importance of community, the power of sacrifice for the greater good, and the enduring strength of the human spirit. In a world increasingly fragmented and disconnected, the Lakota concept of Mitakuye Oyasin – All My Relations – offers a timeless and essential message of unity, respect, and the sacredness of all life. Their spiritual heart beats on, strong and resilient, echoing the sacred wisdom of the plains for generations to come.