Las Trampas: Where Time and Querencia Converge in the Sangre de Cristos

The light in northern New Mexico is unlike any other. It falls in liquid gold across the ancient adobe, sharpens the contours of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, and seems to imbue every shadow with a story. Here, nestled within a fold of that majestic range, along what’s known as the High Road to Taos, lies Las Trampas. It’s a place that whispers of centuries, a living testament to a heritage carved out of isolation, faith, and an unbreakable bond with the land. More than just a picturesque village, Las Trampas is a pulsating heart of querencia – a deep, almost spiritual sense of belonging to a place – where the past isn’t merely remembered, but actively lived.

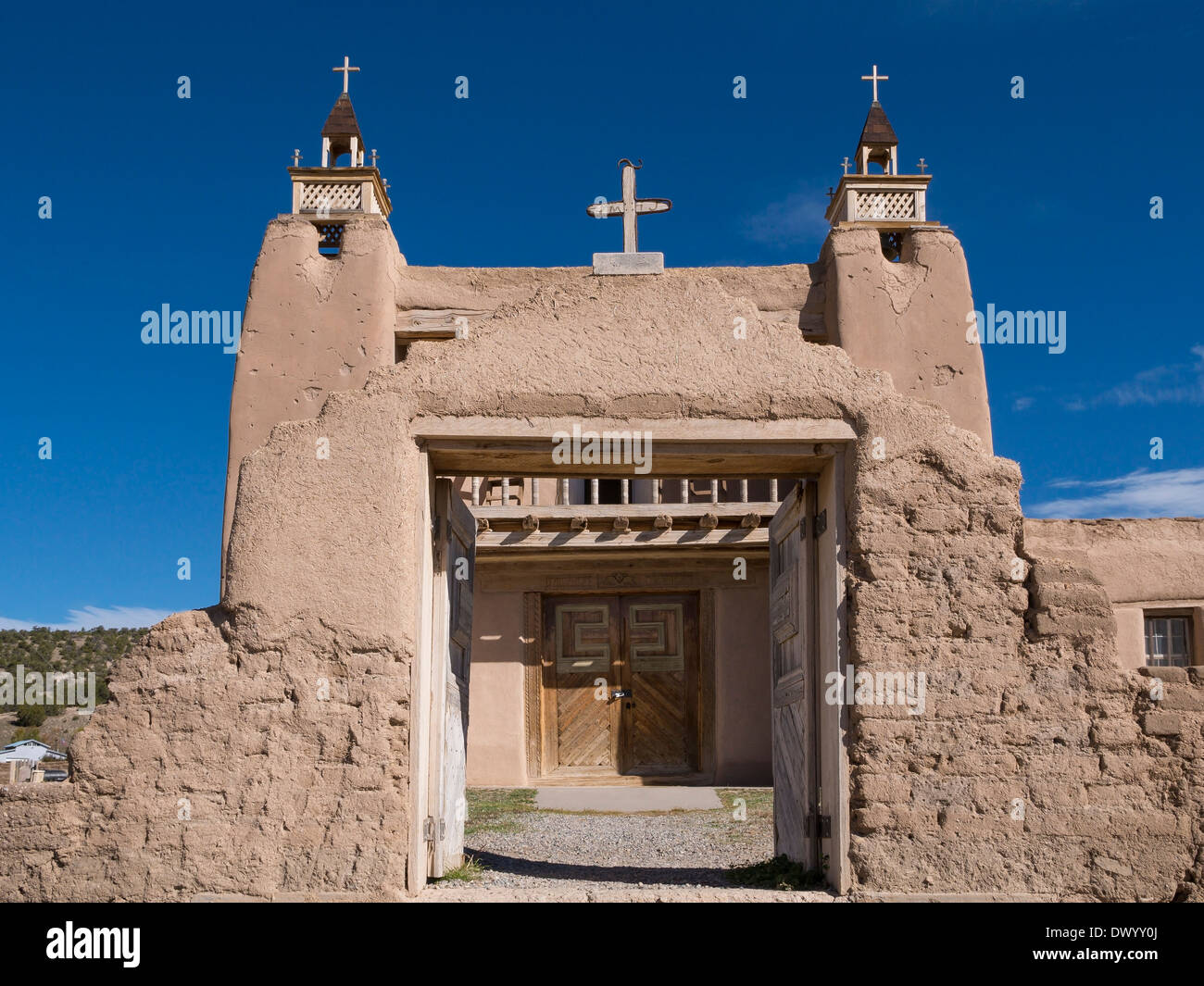

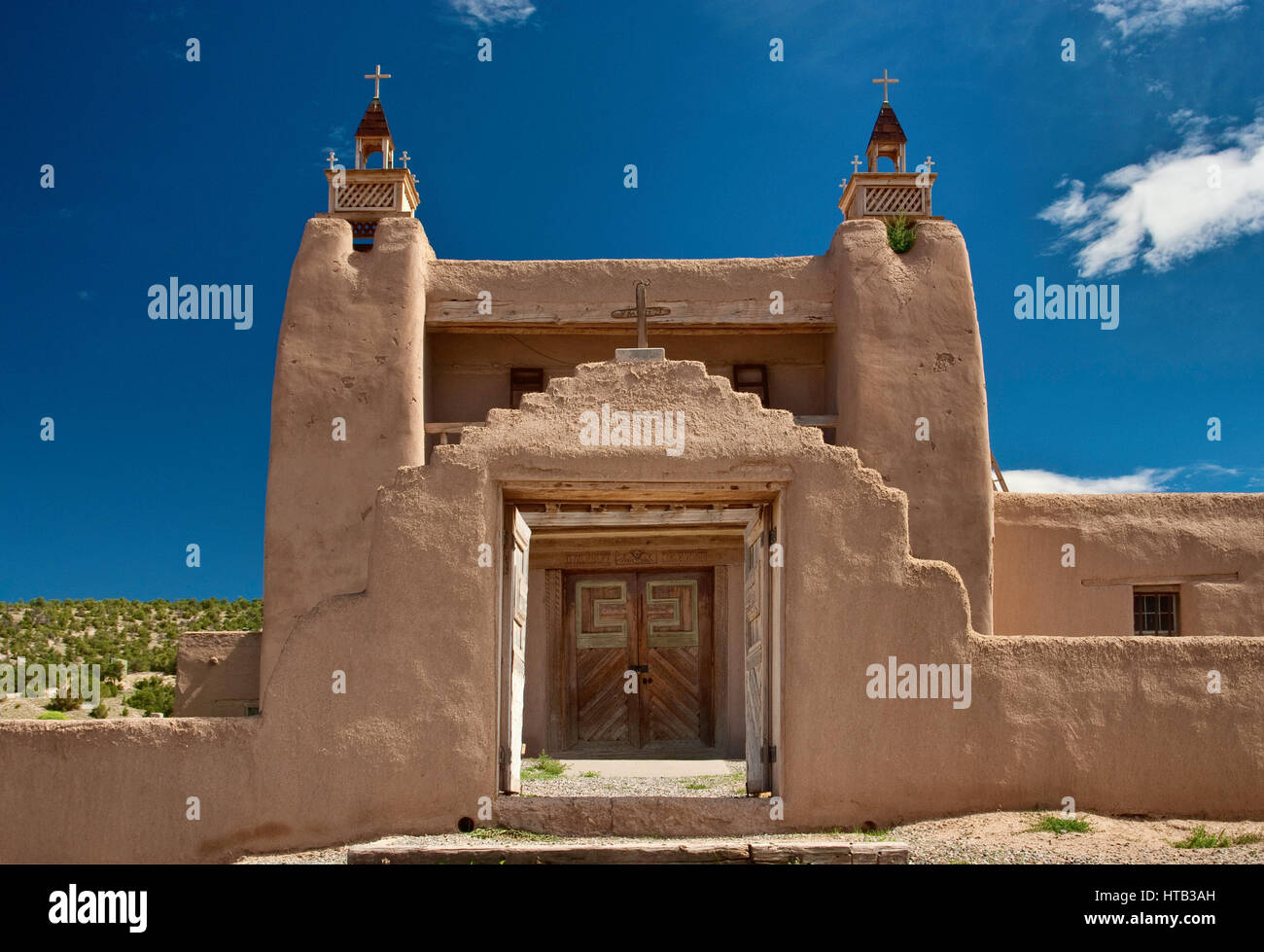

To step into Las Trampas is to step back in time. The narrow, unpaved roads, the venerable adobe homes, many still bearing the marks of generations of hands, and the ubiquitous presence of the towering San José de Gracia Church, all conspire to create an atmosphere of profound historical depth. It’s a world away from the hurried pace of modern life, a sanctuary where the rustle of cottonwoods and the murmur of the acequia often drown out any other sound. Yet, this is no museum; it is a vibrant, albeit quiet, community, fiercely guarding its traditions and its identity against the relentless tide of change.

The Crucible of Isolation: A History Forged in Faith and Frontier

The story of Las Trampas begins in 1751, when a group of twelve families from Santa Fe petitioned King Ferdinand VI of Spain for a land grant. They sought refuge from the encroaching Ute and Comanche raids that plagued the more settled areas, and a place to establish a new frontier outpost. Their request was granted, and the "Santo Tomás Apostol del Río de las Trampas" land grant was established, a vast tract of communal land designed to support a self-sufficient agricultural community. The name, "Las Trampas" – meaning "the traps" – is believed to refer to the natural traps in the nearby mountains used to catch game, or perhaps the strategic position of the settlement itself.

This was no easy life. The settlers, or colonos, were true pioneers, facing harsh winters, arid summers, and constant threats from indigenous tribes. Their isolation, however, proved to be a powerful, if unintended, preserver of culture. Cut off from the larger Spanish colonial centers, the community developed a unique blend of Spanish and indigenous traditions, language, and customs that would endure for centuries. The Spanish spoken in Las Trampas, for instance, retains archaic forms and vocabulary that have long since disappeared from standard Castilian.

At the heart of this enduring community stands the magnificent San José de Gracia Church. Begun in 1760 and largely completed by 1776, it is considered one of the finest surviving examples of Spanish colonial mission architecture in the United States. Its massive adobe walls, nearly seven feet thick at the base, and its twin bell towers speak to the monumental effort of its builders, who used local materials – earth, timber, and stone – to construct a spiritual fortress. Inside, the church is a treasure trove of religious art, including santos (carved wooden saints) and retablos (painted panels) crafted by local santeros (saint makers) like José Rafael Aragón and Fray Andrés García, whose works reflect a distinctive regional style.

"The church isn’t just a building; it’s our soul," explains Elena Montoya, a lifelong resident whose family has lived in Las Trampas for generations. "It’s where we gather, where we celebrate, where we mourn. Every adobe brick, every beam, holds the prayers of our ancestors. It’s a testament to their faith and their struggle." Designated a National Historic Landmark in 1967, the church is not merely an object of historical interest but remains an active parish church, central to the spiritual and social life of the community.

The Rhythms of Life: Acequias, Adobe, and Ancestors

Life in Las Trampas, even today, moves to rhythms dictated by the seasons and the land. The acequia system, an intricate network of irrigation ditches brought from Spain and perfected by Moorish engineers, is the lifeblood of the village. These communal ditches, fed by mountain runoff, deliver precious water to the fields and gardens, sustaining crops of chile, corn, and beans. The annual limpia de acequia, or cleaning of the acequia, is a vital community event, bringing residents together in shared labor and reinforcing the bonds of mutual dependence that have defined the village for centuries.

"The acequia teaches us that we are all connected," says Miguel Chávez, who serves on the acequia commission. "If one person doesn’t do their part, everyone suffers. It’s a lesson we learn from childhood, a lesson about community and responsibility that’s almost forgotten in other places."

The homes themselves are a reflection of this connection to the earth. Built of adobe – sun-dried earth bricks – they blend seamlessly into the landscape. These thick-walled structures provide natural insulation, keeping interiors cool in summer and warm in winter. Many still feature vigas (exposed wooden ceiling beams) and latillas (smaller wooden poles laid crosswise), showcasing the traditional building techniques passed down through generations. These aren’t just houses; they are extensions of the land, imbued with the spirit of those who built and lived in them.

This profound connection to place, to land, and to community is encapsulated by the concept of querencia. It’s a Spanish word that lacks a direct English translation but signifies a deep, almost visceral attachment to one’s homeland, a feeling of belonging and rootedness that transcends mere ownership. It’s the feeling a bull has for its home territory in the arena, where it feels strongest. In Las Trampas, querencia is palpable. It’s in the way elders speak of their childhoods, in the way younger generations, even those who have left for opportunities elsewhere, often feel an irresistible pull to return.

Echoes of the Past, Challenges of the Present

Despite its enduring charm and historical significance, Las Trampas is not immune to the challenges of the 21st century. Economic opportunities are scarce, leading many younger residents to seek work in larger towns like Santa Fe or Española. The population has dwindled, and the average age of residents has steadily increased. Maintaining the historic adobe structures requires constant effort and resources, often beyond the means of the families who inhabit them.

"It’s a struggle, no doubt," admits Clara Romero, a local artist who creates contemporary pieces inspired by traditional New Mexican motifs. "We want to preserve our heritage, but we also need to find ways to make a living, to keep the village alive for the next generation. It’s a delicate balance between tradition and progress."

Tourism, while bringing some economic benefit, also presents a challenge. The village, with its iconic church and picturesque setting, draws visitors eager to experience a slice of authentic New Mexico. However, residents are keen to ensure that their home doesn’t become a mere spectacle. There’s a quiet dignity to Las Trampas, a sense that while visitors are welcome, they are entering a living community, not a theme park. Respect for privacy and local customs is implicitly expected.

The question of land ownership and preservation is another ongoing concern. The original communal land grant system has been eroded over centuries, first by the American acquisition of New Mexico in 1848, and later by legal battles and economic pressures that led to the privatization and fragmentation of lands. Yet, the spirit of communal stewardship, particularly over water rights through the acequias, remains strong. Efforts by preservation groups and local residents aim to protect the integrity of the historic village and its surrounding landscape for future generations.

The Enduring Spirit: Resilience and Hope

Even amidst these challenges, the spirit of Las Trampas remains unbroken. It’s a community defined by resilience, forged over centuries of hardship. The people of Las Trampas are survivors, fiercely proud of their heritage and determined to keep their traditions alive. Cultural events, like feast days for patron saints, continue to be celebrated with gusto, bringing families together and reinforcing the bonds of community.

"We’ve seen a lot of changes, a lot of people leave," says Father Tomás, the current priest of San José de Gracia, his voice echoing in the vast nave of the church. "But the faith, the connection to this land, the stories – they stay. This place has a way of calling its children home, even if only in their hearts. Las Trampas is a reminder that some things are more important than convenience or wealth: community, faith, and the ground beneath your feet."

Las Trampas is more than just a dot on a map or a stop on a scenic drive. It is a profound meditation on endurance, on the power of community, and on the deep human need for querencia. It stands as a living monument to the Spanish colonial past of New Mexico, a place where history isn’t relegated to textbooks but breathes in the adobe walls, flows in the acequia waters, and resonates in the quiet pride of its people. As the golden light of sunset bathes the ancient church and the mountains turn a deep, blood-red hue, one is left with an undeniable sense that in Las Trampas, time doesn’t simply pass; it gathers, deepens, and tells a story that is as vital and enduring as the land itself.