Lee’s Audacious Gamble: The Wilderness’s Grim Triumph at Chancellorsville

The spring of 1863 in Virginia was thick with the scent of pine and the dread of impending battle. For the Union, a new commander, Major General Joseph Hooker, had taken the reins of the Army of the Potomac, determined to wipe away the stain of Fredericksburg and deliver a decisive blow to Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Hooker was a man of immense confidence, perhaps bordering on hubris, who famously declared, "My plans are perfect, and when I start to carry them out, may God have mercy on General Lee, for I will have none." He commanded the largest and best-equipped Union army to date, a force of over 130,000 men, meticulously reorganized and brimming with renewed morale.

Across the Rappahannock River, Lee faced him with an army half its size – a mere 60,000 "ragged rebels," as they were often called, though their spirit was anything but ragged. The disparity in numbers was stark, but Lee possessed an invaluable asset in his lieutenant, Lieutenant General Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson, and an intimate knowledge of the challenging Virginia terrain. What unfolded in the dense, tangled undergrowth of the Wilderness would become one of the most audacious and strategically brilliant, yet ultimately tragic, campaigns of the American Civil War: Chancellorsville.

The Grandest Operations: Hooker’s Master Plan

Hooker’s strategy was indeed ambitious, a complex flanking maneuver designed to bypass Lee’s strong defensive lines at Fredericksburg and force him into open battle on unfavorable ground. He planned to divide his massive force into three main parts:

- The Main Flanking Column: Three corps (V, XI, XII) under his direct command, totaling about 42,000 men, would march far upstream, cross the Rappahannock and Rapidan rivers, and then sweep east, turning Lee’s left flank and cutting off his supply lines.

- The Secondary Flanking Column: Two corps (I, III) under Major General John Reynolds and Major General Daniel Sickles, totaling about 42,000 men, would follow a similar but closer route, crossing the Rapidan at Germanna and Ely’s Fords.

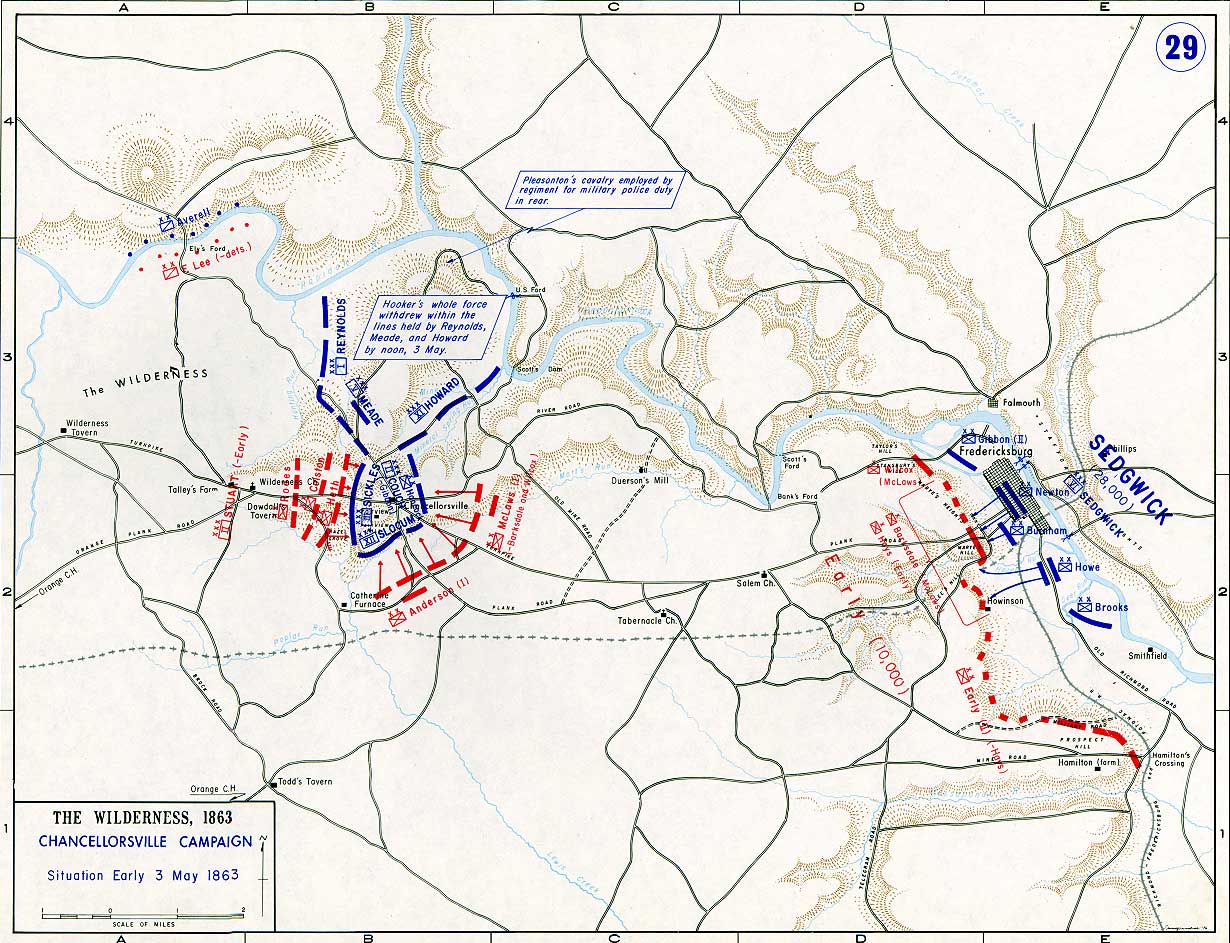

- The Diversionary Force: Two corps (I and VI, initially just VI Corps) under Major General John Sedgwick, about 40,000 men, would remain at Fredericksburg, creating a strong diversion to fix Lee’s attention and prevent him from reinforcing his main body.

By April 27th, the flanking columns were in motion. The weather was favorable, and initial progress was swift. Hooker’s men crossed the rivers largely unopposed, entering the area around a large brick mansion known as Chancellorsville, deep within the tangled scrub and dense second-growth forest known as "the Wilderness." This labyrinthine terrain, characterized by thickets, ravines, and poor visibility, would prove to be a crucial player in the coming battle, negating much of the Union’s numerical superiority and artillery advantage.

On April 30th, Hooker’s main force consolidated at Chancellorsville. He was ecstatic, believing he had outmaneuvered Lee completely. "The Rebel army is now the legitimate property of the Army of the Potomac," he reportedly boasted. His forces were positioned to strike Lee’s rear, forcing the Confederates to abandon their formidable defenses at Fredericksburg or face annihilation.

Lee’s Audacious Gambit: Dividing in the Face of the Enemy

Lee, however, was not one to be easily surprised or intimidated. Receiving intelligence of Hooker’s movements, he faced a critical decision: retreat, dig in, or attack. His audacious nature, coupled with his understanding of Hooker’s cautious temperament once engaged, led him to choose the latter. In a move that defied conventional military wisdom, Lee divided his already outnumbered army.

He left a small force of about 10,000 men under Major General Jubal Early to hold the heights at Fredericksburg against Sedgwick, while he, with the remaining 50,000, marched west to confront Hooker. This initial division was a massive gamble, but it was just the beginning.

On May 1st, Lee’s men, led by Jackson, encountered elements of Hooker’s army west of Chancellorsville. Instead of falling back into prepared positions as Hooker expected, Lee aggressively pushed forward, disrupting Hooker’s advance and forcing him to pull his troops back into the defensive positions he had established around Chancellorsville. This early Confederate aggression stunned Hooker, who, despite his earlier bravado, began to show signs of hesitation. He famously said, "It’s all right, gentlemen; we’re just playing a game of chess." But the game was already turning deadly.

Jackson’s Masterstroke: The Flank March

The night of May 1st, with the two armies locked in a standoff within the Wilderness, brought one of the most daring decisions of the war. Lee and Jackson met under the cover of darkness. Union cavalry had reported a Confederate column moving west, but Hooker dismissed it as a retreat. Lee, however, recognized an opportunity. He asked Jackson, "What do you propose to do?" Jackson, in his characteristic laconic style, replied, "Go around."

The plan was audacious to the point of seeming suicidal: Jackson would take his entire corps – approximately 28,000 men – on a twelve-mile march around the Union right flank, while Lee remained with just 14,000 men to hold the front against Hooker’s overwhelming numbers. If Hooker realized the Confederates had divided their forces again, he could easily crush Lee’s small contingent. But Lee trusted Jackson implicitly, and he trusted his assessment of Hooker’s caution.

On the morning of May 2nd, Jackson’s "foot cavalry" began their epic march. It was a grueling trek through the dense woods, screened from Union view by the very Wilderness that made the terrain so difficult. Although some Union pickets and cavalry patrols spotted parts of Jackson’s column, Hooker remained convinced it was a retreat. Major General Oliver O. Howard, commander of the Union XI Corps holding the extreme right flank, received warnings but failed to take them seriously, leaving his corps dangerously exposed and unprepared for a flank attack.

The Hammer Blow: "The Rebel Yell"

As the sun began to set on May 2nd, Jackson’s corps, having completed their incredible flanking march, burst out of the woods. Their target was the unsuspecting XI Corps, whose men were cooking supper, playing cards, and relaxing, with their rifles stacked and facing south, not west.

The attack was a complete surprise, devastating in its ferocity. With a deafening "Rebel yell," Jackson’s veterans crashed into the Union right. The XI Corps, composed largely of German immigrants and often unfairly maligned, disintegrated under the shock. Panic spread like wildfire, and thousands of Union soldiers fled in disarray, abandoning their weapons and supplies.

Jackson, ever the aggressive commander, rode forward with his staff in the gathering darkness to reconnoiter for a renewed push. He was eager to press the advantage and cut off Hooker’s retreat to the Rappahannock. It was during this reconnaissance, in the confusion and poor visibility of the night, that tragedy struck. As Jackson returned to his lines, he and his staff were mistakenly fired upon by his own pickets. Jackson was hit by three bullets, severely wounding his left arm.

The loss was immediate and profound. Lee, upon hearing the news, famously lamented, "He has lost his left arm, but I have lost my right." Jackson’s arm was amputated, but he contracted pneumonia and died eight days later, on May 10th. His death was an irreplaceable blow to the Confederacy, robbing Lee of his most brilliant and daring field commander.

Hooker’s Paralysis and Sedgwick’s Ordeal

The morning of May 3rd dawned with the Confederate advantage, but also with the chaos of Jackson’s wounding. J.E.B. Stuart, the audacious cavalry commander, reluctantly took temporary command of Jackson’s corps and pressed the attack. The fighting was some of the most intense and brutal of the entire war, a desperate struggle for the vital Chancellorsville crossroads.

Adding to the Union’s woes, Hooker himself was struck by a cannon