Lines of Time, Traces of Power: The Enduring Narrative of American History Maps

They are not mere lines on parchment or pixels on a screen. American history maps are vibrant chronicles, silent witnesses, and potent tools that have shaped, reflected, and often dictated the very course of a nation. From the earliest European attempts to chart an unknown continent to the intricate digital overlays of today, maps tell a story far richer than mere geography. They reveal ambitions, fears, conflicts, and the ever-evolving self-perception of a sprawling, diverse nation. In their contours, colors, and captions, we find the enduring narrative of America, a story of discovery, conquest, expansion, and identity.

The Dawn of a Continent: Imagining the Unknown

The first maps touching upon what would become America were born from a mix of daring exploration, vivid imagination, and often, profound ignorance. For centuries, European cartographers wrestled with the concept of a "New World," often depicting it as a fragmented archipelago or an extension of Asia. The pivotal moment arrived in 1507 when German cartographer Martin Waldseemüller, synthesizing Amerigo Vespucci’s accounts, published his Universalis Cosmographia. This monumental wall map was the first to explicitly label the southern landmass "America," permanently affixing Vespucci’s name to the continent. This wasn’t just a naming; it was a conceptual shift, acknowledging a distinct landmass and forever altering the global understanding of geography.

These early maps, however, were not neutral. They were instruments of imperial ambition, marking territories for European powers with little regard for the indigenous nations who had inhabited these lands for millennia. Coastlines were meticulously charted for navigation and trade, while the vast interiors remained blank, often filled with speculative creatures or simply labeled "Terra Incognita." This cartographic void became an invitation for conquest, a symbolic erasure that preceded the physical displacement of Native American populations. The lines drawn on these maps, though crude, laid the groundwork for future claims and conflicts, embodying the European vision of an unowned, exploitable wilderness.

Forging a Nation: Borders of Revolution and Republic

The American Revolution was fought not only on battlefields but also on maps. British and colonial cartographers painstakingly charted strategic locations, troop movements, and supply routes. Maps became vital intelligence, dictating maneuvers and fortifying positions. George Washington, a former surveyor himself, understood the critical importance of accurate mapping. His reliance on maps for military strategy was legendary, turning geographical knowledge into a weapon of war.

After independence, maps took on a new, profound significance: defining the boundaries of a nascent republic. The Treaty of Paris in 1783, which officially ended the Revolutionary War, was a cartographic triumph, establishing the United States’ western border at the Mississippi River. Yet, the precise delineation of these borders, especially with neighboring Spanish and British territories, remained a source of tension and further negotiation for decades. State lines, once colonial administrative divisions, now represented sovereign entities within a federal system, each demanding clear definition. The Articles of Confederation and later the Constitution, while political documents, relied on these cartographic understandings to establish the very fabric of the nation.

The Great March West: Manifest Destiny and the Vanishing Frontier

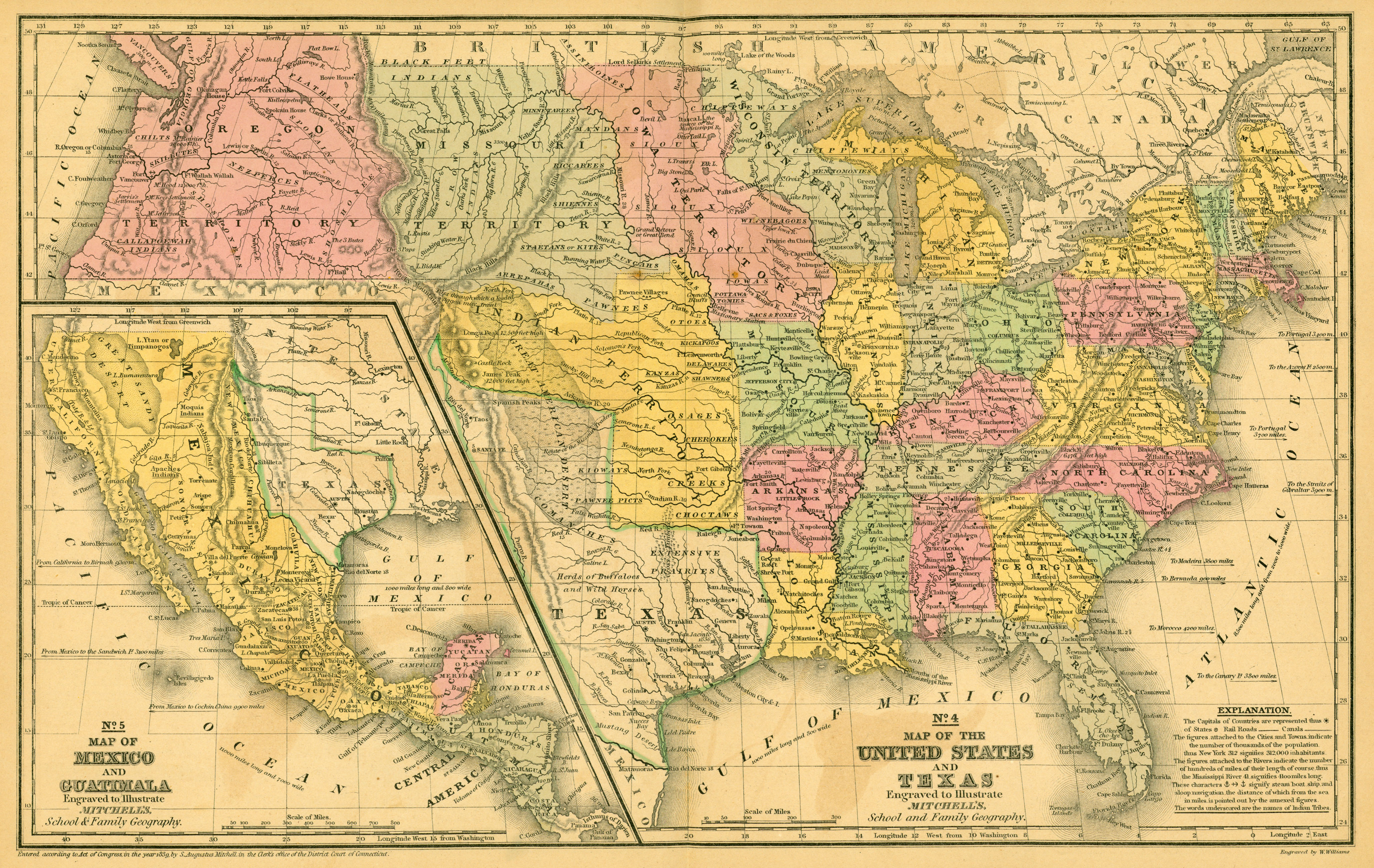

The 19th century witnessed America’s relentless drive westward, a period profoundly influenced and justified by maps. The Louisiana Purchase in 1803, doubling the nation’s size, presented a vast, largely unmapped frontier. Thomas Jefferson’s commissioning of the Lewis and Clark expedition was not merely an act of scientific curiosity; it was a cartographic imperative. Their meticulous journals and maps, though rough by modern standards, provided the first comprehensive survey of the American interior, paving the way for future settlement and resource exploitation.

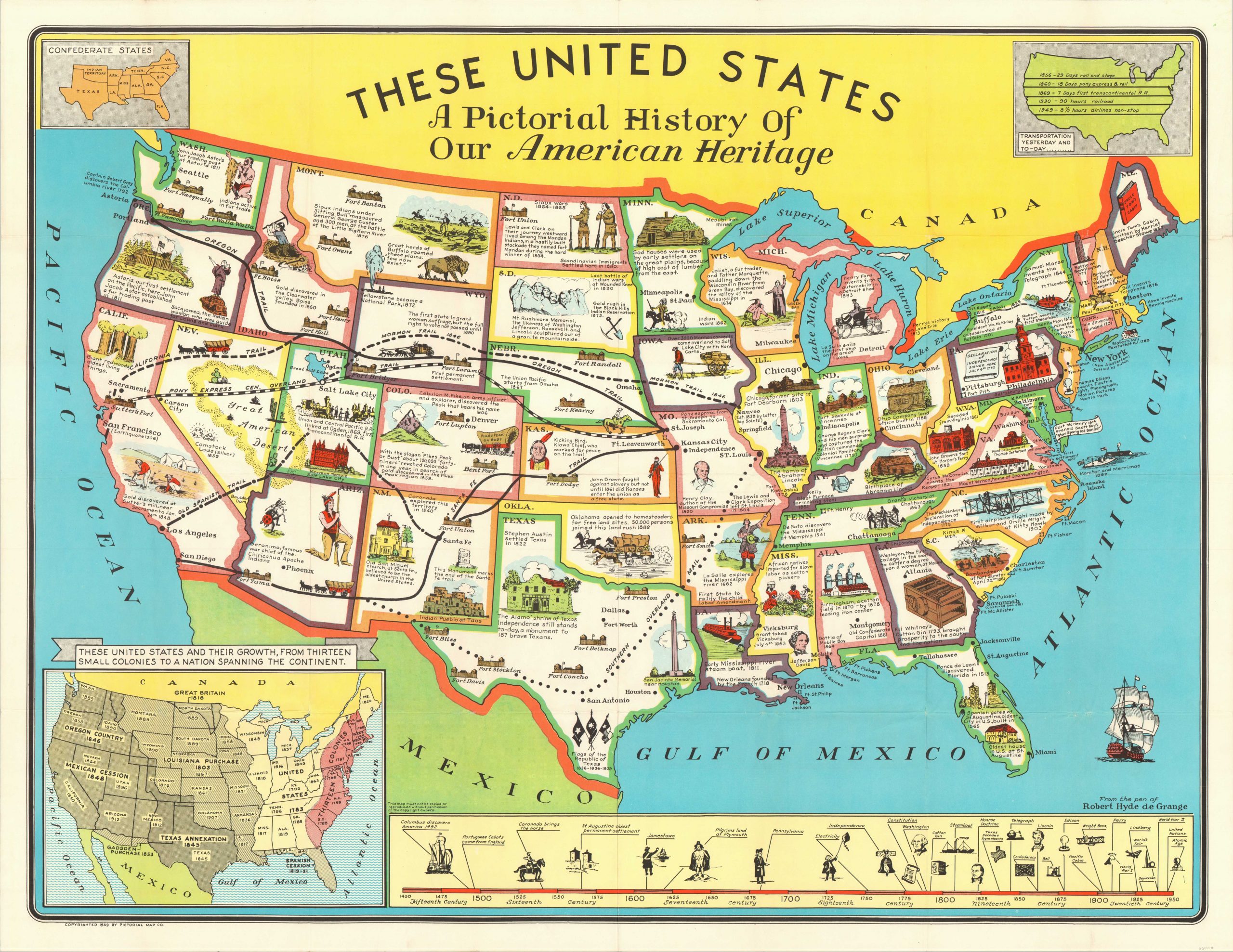

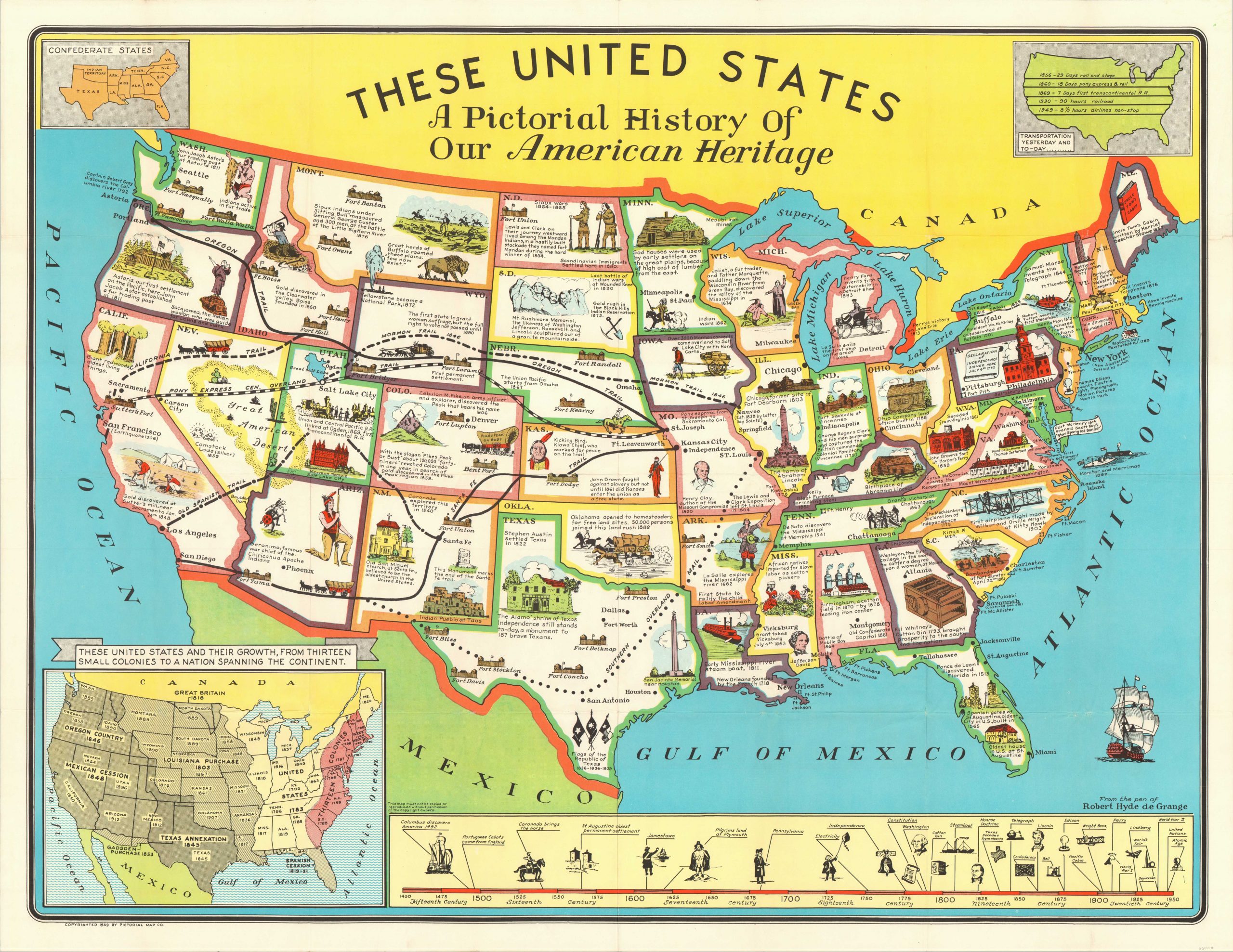

This era was dominated by the ideology of "Manifest Destiny," a term coined by journalist John O’Sullivan in 1845, asserting America’s divinely ordained right to expand across the continent. Maps from this period beautifully illustrate this belief. They show a burgeoning nation, its western territories gradually filling in, often depicting Native American lands as empty spaces ripe for American settlement. The trails of pioneers, the routes of railroads, and the surveys for land grants were all etched onto maps, transforming abstract ideology into tangible progress.

Yet, these maps also tell a story of immense loss. The expansion came at the direct expense of indigenous peoples, whose ancient territories were carved up, renamed, and often forcibly taken. Reservations, isolated pockets of land, began to appear on maps, stark reminders of broken treaties and cultural destruction. The lines of "progress" for one people were lines of dispossession for another.

A Nation Divided and Reunited: Maps of Conflict and Cohesion

The ultimate test of American unity came with the Civil War. Maps became indispensable tools for both Union and Confederate armies, illustrating troop positions, fortifications, battle plans, and supply lines. Generals poured over them, planning movements that would determine the fate of the nation. Maps from this period starkly show the divided nation, the Union blue clashing with Confederate gray, a visual representation of the ideological schism.

After the war, maps played a role in reconciliation and rebuilding. They documented the new political landscape, the abolition of slavery, and the gradual integration of former Confederate states back into the Union. The precise redrawing of district lines during Reconstruction, though often fraught with political maneuvering, reflected the ongoing struggle to define a truly united nation.

As the nation industrialized, maps also began to reflect new challenges and aspirations. City maps grew in complexity, detailing burgeoning urban centers, public works, and the infrastructure of modernity – railroads, canals, and later, telegraph lines. The Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, with their incredibly detailed depictions of urban buildings, construction materials, and utilities, offer a unique cartographic snapshot of American cities at the turn of the 20th century, revealing the intricate patterns of growth and risk.

The Modern Era: From Global Power to Digital Domains

The 20th century saw America emerge as a global power, and maps took on international significance. Maps of World War I and II meticulously tracked battlefronts, supply chains, and strategic objectives across continents. The Cold War era produced maps that visualized geopolitical tensions: Iron Curtains, spheres of influence, and the terrifying reach of nuclear arsenals. These maps were not just descriptive; they were prescriptive, shaping foreign policy and public perception of global threats.

Domestically, maps continued to evolve, reflecting social and demographic changes. The rise of scientific cartography and Geographic Information Systems (GIS) allowed for the mapping of complex data: poverty rates, migration patterns, disease outbreaks, and electoral demographics. Maps became powerful tools for social analysis, urban planning, and political campaigning, revealing hidden patterns and disparities within American society.

The advent of the digital age has revolutionized mapping. Google Maps, Waze, and countless other online platforms have made maps ubiquitous and interactive. No longer static documents, they are dynamic, personalized, and constantly updated. Yet, even in this digital frontier, the fundamental power of maps remains. They still guide us, inform us, and shape our understanding of the world. They still carry biases, whether intentional or accidental, in their algorithms and data selections.

The Enduring Legacy: Maps as Mirrors and Makers of History

American history maps are more than geographical records; they are cultural artifacts, political statements, and economic blueprints. They tell us not just where things were, but what people believed, what they valued, and what they aspired to. They reveal the stories of explorers pushing into the unknown, of politicians carving out territories, of soldiers fighting for ideals, and of communities building new lives.

From Waldseemüller’s audacious naming of a continent to the intricate satellite imagery of today, maps have consistently served as both mirrors, reflecting the prevailing understanding and ideology of their time, and makers of history, influencing decisions that profoundly altered the national landscape. They remind us that the lines on a map are rarely neutral; they are imbued with power, perspective, and the indelible traces of human endeavor. To understand American history, one must learn to read its maps – for within their contours lies the very soul of the nation, constantly being drawn and redrawn.