Louisiana’s Fading Echoes: The Red River Campaign, A Union Gamble Gone Awry

The spring of 1864, four years into the brutal American Civil War, found the Union high command hungry for a decisive victory. While Grant pressed Lee in Virginia and Sherman marched on Atlanta, a lesser-known but equally ambitious campaign was conceived in the vast, often overlooked Trans-Mississippi Department. This was the Red River Campaign, a grand strategic gamble aimed at seizing Shreveport, Louisiana – the Confederate capital of the Trans-Mississippi – securing the region’s valuable cotton, and potentially striking into Texas. What unfolded, however, was not a swift triumph but a prolonged, bloody, and ultimately disastrous expedition that would forever mark the bayous and pine forests of Louisiana.

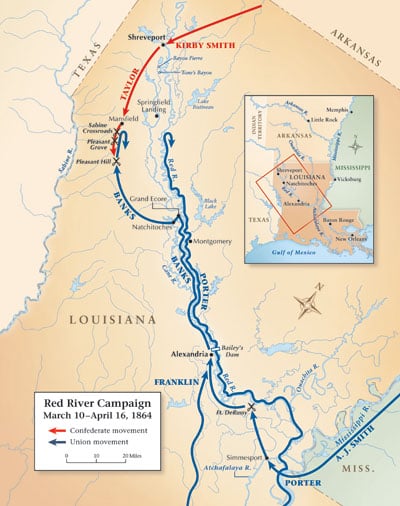

The architect of this audacious plan was Major General Nathaniel P. Banks, a former Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives and Governor of Massachusetts, whose political connections far outstripped his military acumen. Banks commanded the Department of the Gulf, and for him, the Red River offered a path to glory, cotton, and perhaps even a presidential nomination. His objectives were multi-faceted: control of the Red River for its strategic transportation, confiscation of vast quantities of Confederate cotton for Northern mills, and the establishment of a Union presence in Texas to discourage French intervention in Mexico. The plan was complex, requiring a coordinated effort between Banks’s 20,000-strong land forces, Major General Andrew J. Smith’s 10,000 veterans detached from Sherman’s army, and Rear Admiral David D. Porter’s formidable fleet of gunboats and transports.

The campaign kicked off in early March 1864. Smith’s contingent, traveling by river, captured Fort DeRussy on March 14th, a key Confederate bastion guarding the Red River approach, before linking up with Banks’s main force in Alexandria. The early stages seemed promising. Porter’s fleet, a collection of ironclads, tinclads, and rams, steamed confidently up the Red, its gun barrels bristling, ready to support the ground troops. The river, though shallow in places, was passable, and the Union advance through the heart of Confederate Louisiana began.

However, the Confederates, though outnumbered, were far from idle. Commanding the Department of West Louisiana was Major General Richard Taylor, son of former President Zachary Taylor, a pugnacious and brilliant tactician who knew the local terrain intimately. Taylor understood that Banks’s elongated supply lines and reliance on the river made him vulnerable. His forces, a mix of seasoned Louisiana and Texas infantry, and formidable cavalry under Brigadier General Thomas Green, were determined to defend their homeland.

The Union advance, initially swift, began to slow as they pushed beyond Alexandria, heading towards Natchitoches and ultimately Shreveport. Banks, perhaps overly confident, made a critical error: he separated his forces. Smith’s veterans, trained for independent action, were often ahead, while Banks’s main column, heavily encumbered with wagons and an ever-increasing number of confiscated cotton bales, stretched for miles along the narrow, dusty roads. The terrain, unfamiliar to many Union soldiers, was a labyrinth of thick woods, tangled undergrowth, and treacherous ravines – ideal for ambushes.

The first major confrontation, and indeed the turning point of the campaign, occurred on April 8th near Mansfield, Louisiana, at a place also known as Sabine Cross Roads. Banks’s lead division, under Brigadier General Albert L. Lee, encountered Taylor’s entrenched Confederate forces. Despite being urged to halt and consolidate his troops, Banks pressed forward. Taylor, seizing the opportunity, launched a ferocious attack on the strung-out Union column. "The enemy struck our advance in column on the march," wrote one Union officer, "and rolled it up like a scroll."

The Confederate assault was swift and devastating. Lee’s division, surprised and outmaneuvered, broke and fled. Brigadier General William H. Emory’s division, sent forward as reinforcements, met a similar fate. The roads became choked with fleeing Union soldiers, abandoned wagons, and artillery pieces. The chaos was absolute. One Union soldier later recounted the scene as "a perfect rout, horses and men tumbling over each other, and all flying for their lives." It was only the timely arrival of Brigadier General William Dwight’s division, which formed a desperate defensive line, that prevented a complete collapse and allowed the Union forces to retreat to Pleasant Hill, a few miles back.

The Battle of Mansfield was a stunning Confederate victory, inflicting heavy casualties and shattering Union morale. Banks’s forces lost over 2,500 men, 20 cannons, and hundreds of wagons. Taylor, though outnumbered, had effectively exploited Banks’s tactical blunders.

The following day, April 9th, the two armies clashed again at Pleasant Hill. Banks, reinforced by Smith’s contingent, which had been recalled from its forward position, decided to make a stand. The battle was fierce and bloody, a swirling melee of charges and countercharges in the dense woods. By nightfall, the Confederates, despite inflicting heavy losses on the Union, were themselves exhausted and disorganized. Taylor, believing he had won a tactical victory, ordered his troops to withdraw, a decision that would later cause friction with his superior, General Edmund Kirby Smith. While the Union technically held the field, it was a pyrrhic victory. Banks, still reeling from Mansfield and facing dwindling supplies, made the grim decision to abandon the advance on Shreveport and begin a full retreat back down the Red River.

The retreat proved to be as arduous and perilous as the advance. Confederate cavalry, sensing blood, relentlessly harassed the Union columns, striking at their flanks and rear. The Red River itself, which had been the Union’s highway, now became its greatest threat. The water level began to drop precipitously, a common occurrence in late spring, threatening to strand Porter’s entire fleet far upstream.

Porter, with 10 ironclads and numerous transports, found his vessels trapped above the rapids at Alexandria. The river had fallen so low that the gunboats, drawing six feet of water, could not pass. Desperation set in. The prospect of abandoning his powerful fleet to the Confederates was unthinkable. It was then that Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Bailey, an engineer from Wisconsin, proposed a daring solution: build a series of wing dams to raise the water level.

Initially met with skepticism, Bailey’s plan was adopted out of sheer necessity. Thousands of Union soldiers, working day and night under the constant threat of Confederate attack, felled trees, gathered rocks, and salvaged lumber from nearby buildings. They constructed a massive timber dam across the river, creating a bottleneck that would increase the water’s depth. It was an engineering marvel born of desperation. On May 8th, the dam broke under the immense pressure, and the trapped gunboats, riding the surge of water, managed to clear the rapids. "The water had risen sufficiently," Porter exclaimed, "and all the vessels were over!" It was a breathtaking escape, saving the Union navy from an ignominious fate, but it had consumed precious time and resources.

Even after clearing the rapids, the retreat was far from over. Taylor’s forces, though still smarting from Pleasant Hill, continued their harassment. A final, significant engagement occurred on May 18th at Yellow Bayou (also known as Monett’s Ferry), where Union forces, acting as a rearguard, fought a fierce battle to protect their crossing of the Atchafalaya River. The Confederates, again under Green’s cavalry (who was killed in an earlier skirmish), attacked fiercely but were repulsed, allowing the Union troops to complete their withdrawal.

By May 20th, the battered Union forces had finally reached Simmesport, Louisiana, and began boarding transports for their return to New Orleans. The Red River Campaign was over. It had been an unmitigated disaster for the Union. Banks’s forces suffered over 5,000 casualties – killed, wounded, or captured – and lost vast quantities of equipment. The primary objectives – Shreveport, Texas, and the cotton – remained firmly in Confederate hands. Politically, the campaign was a humiliation for Banks, effectively ending his military career and dimming his presidential ambitions.

For the Confederates, the campaign was a significant defensive victory, boosting morale in the Trans-Mississippi Department. Richard Taylor emerged as a hero, his tactical prowess undeniable. However, the victory was short-lived and did little to alter the overall trajectory of the war. Kirby Smith’s controversial decision to redirect a portion of Taylor’s victorious forces to Arkansas, rather than allowing him to pursue Banks more aggressively, became a source of lasting bitterness between the two Confederate generals.

The Red River Campaign stands as a poignant reminder of the complexities and brutal realities of the Civil War. It highlighted the challenges of combined operations, the dangers of poor leadership, and the unforgiving nature of the Louisiana landscape. For the people of Louisiana, it left scars both physical and emotional, as towns like Alexandria were partially destroyed by Union troops during the retreat, and the state’s resources were further depleted.

Today, the battlefields of Mansfield, Pleasant Hill, and the sites of Bailey’s Dam stand as silent witnesses to this ill-fated gambit. The Red River, still flowing through the heart of Louisiana, carries with it the echoes of gunboats, the cries of soldiers, and the lingering memory of a campaign that, though often overshadowed by the grander struggles of the East, played a crucial and bloody role in the tragic tapestry of the American Civil War. It was a gamble that cost dearly, cementing its place as one of the Union’s most significant and forgotten fiascoes.