Marcus Whitman: Pioneer, Missionary, Martyr, or Agent of Empire?

More than a century and a half after his violent death, Marcus Whitman remains an enigmatic and profoundly polarizing figure in American history. To some, he was a selfless pioneer and missionary, a medical doctor who sacrificed his life bringing civilization and salvation to the untamed American West. To others, he embodies the destructive arrogance of Manifest Destiny, an unwitting agent of cultural destruction whose good intentions paved a road to tragedy. His story, deeply intertwined with the early settlement of the Oregon Territory and the tragic clash of cultures, continues to provoke debate, inviting us to reconsider the complex legacies of westward expansion.

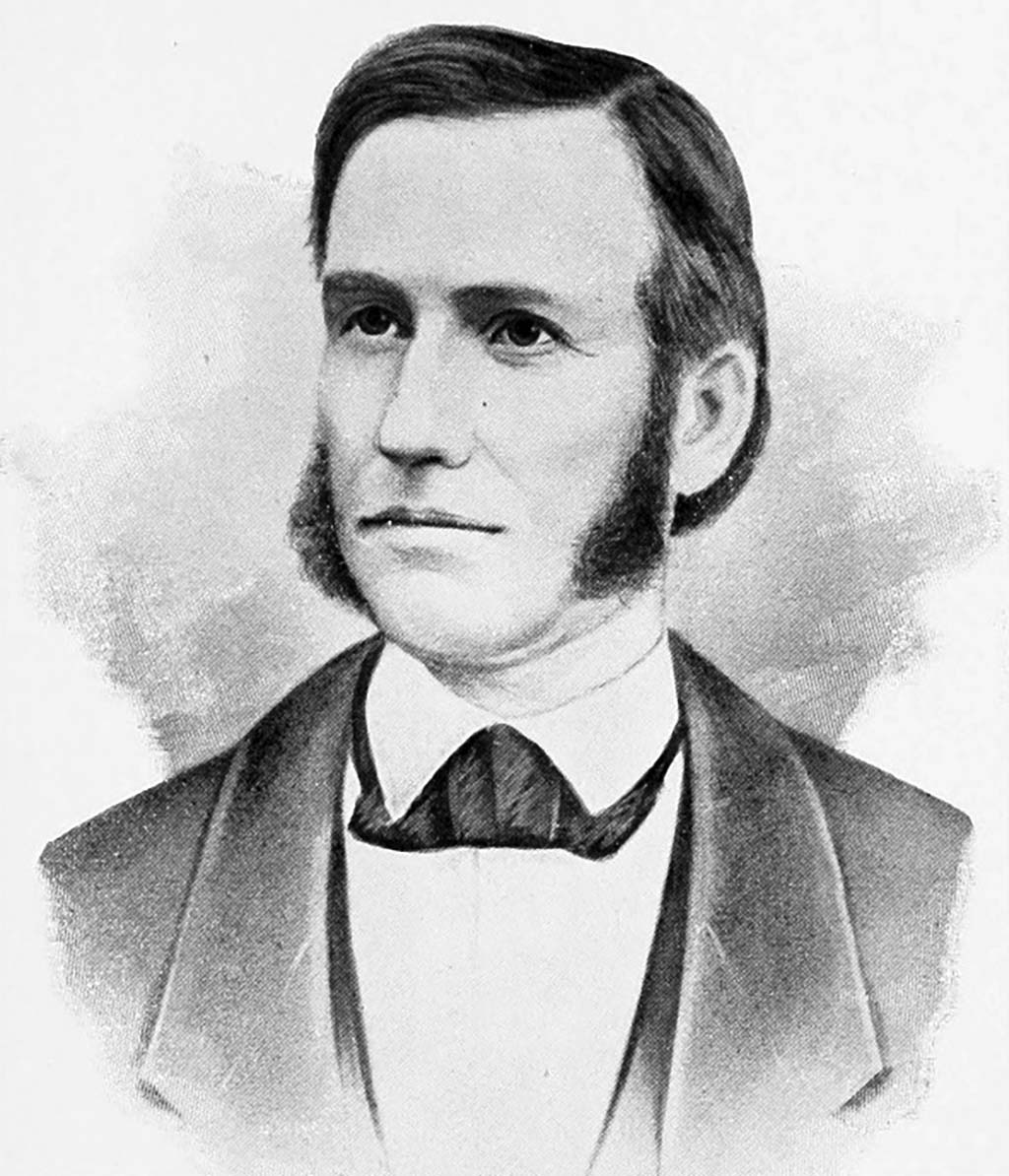

Born in 1802 in Rushville, New York, Marcus Whitman was a man shaped by the fervent religious revivalism of the Second Great Awakening and the era’s burgeoning spirit of exploration. Trained as a physician, he possessed a potent blend of scientific curiosity and evangelical zeal. It was a calling to serve, not just the body but also the soul, that drew him away from a comfortable life in the East and towards the distant, unexplored territories beyond the Rocky Mountains. The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM), a prominent Protestant organization, became the vehicle for his ambition, seeking to establish missions among the Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest.

In 1836, Whitman embarked on what would become a legendary journey. Accompanied by his new wife, Narcissa Prentiss Whitman, and fellow missionaries Henry and Eliza Spalding, they set out for the Oregon Country. Narcissa, alongside Eliza Spalding, achieved a notable first: they were among the very first white women to successfully cross the formidable Rocky Mountains, a feat that captured the imagination of the nation and inspired countless others to follow. Their arduous trek, fraught with danger and hardship, proved that families could survive the journey, effectively blazing a trail that would soon become the iconic Oregon Trail, funneling thousands of settlers westward.

Upon reaching their destination, the Whitmans established their mission, Waiilatpu, near present-day Walla Walla, Washington, among the Cayuse people. The name "Waiilatpu" itself, meaning "place of the rye grass" in the Cayuse language, suggests a fertile ground, but it would soon become a place of profound discord. Here, Marcus Whitman set about his dual mission: to convert the Cayuse to Christianity and to provide medical care. He constructed a mill, planted crops, and opened a school, attempting to introduce a settled, agricultural lifestyle that he believed was essential for their spiritual and temporal salvation.

Initially, the relationship between the missionaries and the Cayuse was one of cautious mutual interest. The Cayuse, a semi-nomadic tribe whose traditional territory encompassed the fertile lands around the Walla Walla River, were interested in the white settlers’ goods, agricultural knowledge, and perhaps even some aspects of their religion. Whitman, for his part, genuinely sought to heal and teach. His medical skills, particularly his ability to treat injuries and some diseases, earned him a degree of respect.

However, the cultural chasm between the two groups was vast and ultimately insurmountable. The Cayuse had a sophisticated, communal understanding of land ownership, viewing it as something to be shared and stewarded, not bought, sold, or exclusively possessed. Whitman, a product of a society rooted in private property, established a mission farm and claimed portions of land, a concept alien and often offensive to the Cayuse. Their spiritual beliefs were deeply intertwined with their land and traditions, making wholesale conversion to Christianity a difficult proposition. The Cayuse also practiced their own forms of medicine, relying on shamans and traditional remedies, which often clashed with Whitman’s Western medical practices.

Tensions began to mount as more white settlers, emboldened by the Whitmans’ successful journey and lured by the promise of free land, began pouring into the Oregon Country. Marcus Whitman himself played a direct role in encouraging this influx. In 1842-43, concerned about the future of his mission and the perceived threat of Catholic influence and British claims in the region, he undertook another grueling winter journey back East. His primary purpose was to consult with the ABCFM, but during his trip, he also became an ardent advocate for American settlement in Oregon. He met with government officials and, upon his return, guided a large wagon train of nearly a thousand settlers westward, demonstrating the feasibility of the Oregon Trail for large-scale emigration. This act, while celebrated by many as patriotic, irrevocably altered the demographics and power balance of the region.

The growing presence of white settlers brought with it not only land disputes but also devastating diseases against which the Indigenous populations had no immunity. Measles, smallpox, and other infectious diseases swept through Native communities like wildfire, decimating populations and creating profound fear and resentment. The year 1847 proved to be the tragic climax of these escalating tensions. A severe measles epidemic gripped the Waiilatpu mission and surrounding Cayuse villages. Marcus Whitman, the dedicated physician, worked tirelessly, administering remedies and trying to save lives.

However, the results were heartbreakingly disparate. While some white children, exposed to measles in childhood, possessed a degree of immunity and often recovered, the Cayuse children, never before exposed, succumbed in droves. Their death rate was exponentially higher. This stark difference in survival rates fueled a terrifying suspicion among the Cayuse. In their traditional culture, a healer who failed to cure was often viewed with suspicion, sometimes even as a sorcerer. The Cayuse believed that Whitman, a powerful white medicine man, was intentionally poisoning their people to make way for the increasing numbers of white settlers. This belief, while unfounded in Western medical terms, was entirely rational within their cultural framework and their observation of the devastating outcome.

On November 29, 1847, the simmering tensions boiled over into unspeakable tragedy. A group of Cayuse men, driven by grief, fear, and a desperate desire for retribution, attacked the Waiilatpu mission. Marcus Whitman was struck down first, followed by Narcissa and eleven others. The attack resulted in the deaths of thirteen white settlers and the abduction of 53 women and children, who were held captive for several weeks before being ransomed.

The "Whitman Massacre," as it came to be known, sent shockwaves across the nation. It ignited the Cayuse War, a protracted conflict between the Cayuse and the newly formed Provisional Government of Oregon, which lasted for several years and ultimately led to the subjugation and displacement of the Cayuse people. More broadly, the massacre provided a powerful catalyst for the United States government to establish the Oregon Territory in 1848, bringing the region under federal control and accelerating the process of American annexation and settlement.

In the immediate aftermath and for many decades that followed, Marcus Whitman was widely hailed as an American hero and a Christian martyr. His image became intertwined with the narrative of Manifest Destiny – the belief in America’s divinely ordained right to expand westward. He was portrayed as a selfless pioneer who opened the West, bringing civilization and the gospel to a "savage" land, only to be cruelly murdered for his efforts. Whitman College in Walla Walla, established in his honor, and numerous monuments across the Pacific Northwest stand as testaments to this heroic interpretation.

However, historical understanding is rarely static. In recent decades, a more nuanced and critical re-evaluation of Marcus Whitman’s legacy has emerged, driven by a greater recognition of Indigenous perspectives and a deeper understanding of the complexities of colonialism and cultural clash. Historians now often view Whitman not just as a hero, but as a complex figure caught in the inexorable tide of westward expansion.

Critics argue that while Whitman may have held genuine benevolent intentions, he was ultimately a product of his time and culture, unable or unwilling to fully comprehend or respect the deeply rooted traditions and sovereignty of the Cayuse. His efforts to "civilize" them, by replacing their communal way of life with sedentary farming and their spiritual beliefs with Christianity, were inherently disruptive and culturally imperialistic. His encouragement of white emigration, while vital to the American claim on Oregon, directly contributed to the land pressures, resource depletion, and disease outbreaks that ultimately led to the Cayuse’s desperation.

From this perspective, the massacre, while horrific, can be understood as a tragic, desperate act of a people pushed to the brink, responding to an existential threat to their culture, land, and lives. The Cayuse were not simply "savage" aggressors but a people reacting to profound and destabilizing forces beyond their control, exacerbated by a deadly epidemic and a profound misunderstanding of medical practices.

The saga of Marcus Whitman, therefore, is more than just a historical account; it is a powerful parable about the profound and often tragic consequences of cultural encounter. It forces us to confront uncomfortable questions about the nature of heroism, the justifications for expansion, and the enduring scars of colonialism. Whitman was undeniably a man of courage and conviction, dedicated to his faith and his medical practice. Yet, he was also a symbol, both then and now, of the forces that irrevocably altered the landscape and the lives of the Indigenous peoples of the American West. His story serves as a potent reminder that history is rarely black and white, and that the same events can be viewed through vastly different, equally valid lenses, depending on whose perspective is given voice. In understanding Marcus Whitman, we are compelled to understand not just one man, but the entire, complex tapestry of American expansion and its indelible impact on the nation it created.