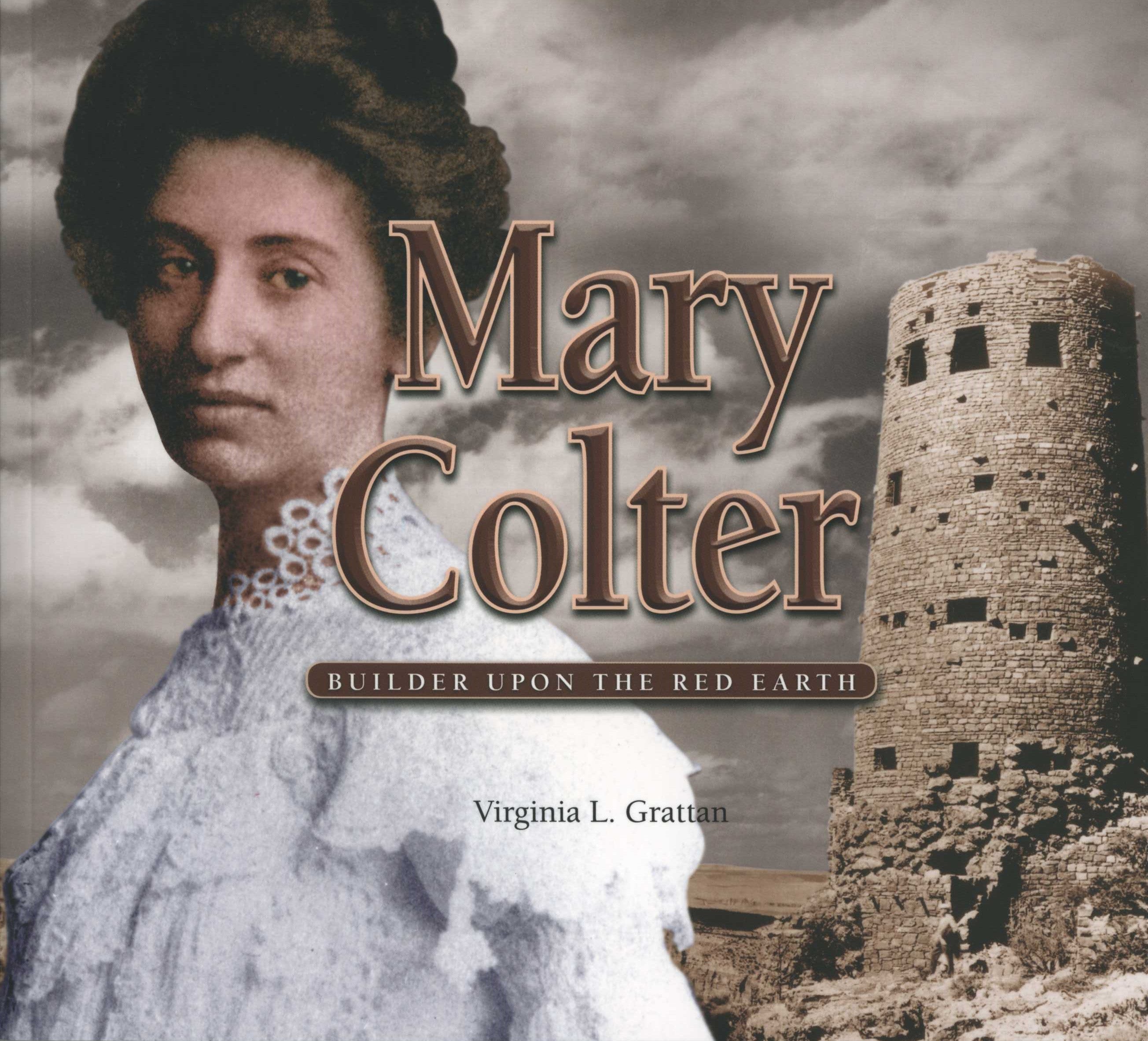

Mary Colter: The Visionary Who Built the Soul of the American Southwest

Imagine standing on the precipice of the Grand Canyon, the vast chasm stretching before you, a silent testament to eons of geological artistry. As your gaze sweeps across the breathtaking panorama, it invariably settles on structures that seem to rise organically from the very rock, their lines echoing the dramatic contours of the landscape. A rustic lodge, a stone watchtower, a humble rest stop – these are not mere buildings; they are integral parts of the experience, designed to enhance, not detract from, nature’s grandeur. These are the indelible marks of Mary Elizabeth Jane Colter, a pioneering architect and designer whose name, though perhaps not as widely recognized as her male counterparts, is etched into the very soul of the American Southwest.

Born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in 1869, Mary Colter embarked on a path that few women of her era dared to tread. After studying art and design at the California School of Design, she spent several years as a teacher in St. Paul, Minnesota. Yet, the call of the West, with its stark beauty, rich indigenous cultures, and nascent tourism industry, proved irresistible. It was a time when the Santa Fe Railway, in partnership with the Fred Harvey Company, was transforming travel, bringing the wonders of the Southwest within reach of an eager public. They needed someone with a keen eye, a deep appreciation for regional aesthetics, and an unparalleled commitment to authenticity to design the hotels, restaurants, and gift shops that would house and entertain these intrepid travelers. In Mary Colter, they found their visionary.

Colter joined the Fred Harvey Company in 1902 and remained with them for an astonishing 46 years, leaving behind a legacy of iconic structures that define the very essence of Southwestern architecture. Her philosophy was revolutionary for its time: she believed that buildings should not merely occupy a space but should emerge from it, mirroring the environment and respecting the indigenous cultures that had long inhabited the land. "Never build two things alike," she famously declared, a mantra that guided her every project. She was a fierce advocate for local materials, often insisting on hand-hewn timber, native stone, and rough-plastered walls, all designed to give her buildings a sense of timelessness and belonging. She wasn’t just building structures; she was crafting experiences, each a carefully curated journey into the heart of the American West.

Her most celebrated work is undoubtedly at the Grand Canyon. Here, amidst one of the world’s most awe-inspiring natural wonders, Colter’s genius truly shone. Take Hermit’s Rest (1914), perched on the canyon rim at the end of Hermit Road. Designed as a rustic way station, it appears as if it has always been there, its massive, rough-hewn stone fireplace and low-slung profile blending seamlessly into the landscape. Colter insisted that the structure look "aged" from day one, instructing workers to collect "junk" from old mining camps and even allowing smoke to stain the interior walls to achieve a patinated effect. It was an early exercise in what we now call "contextual architecture," a deep respect for place that predated the term itself.

Adjacent to Hermit’s Rest is Lookout Studio (1914), another Colter masterpiece. Carved directly into the canyon’s edge, it mimics the ancient Pueblo dwellings, almost disappearing into the rock formations. Its multiple viewing platforms and rough-cut stone walls offer unparalleled vistas, inviting visitors to become part of the geological drama unfolding before them. Like many of her buildings, it features an abundance of windows, framing the natural beauty as if it were a living painting.

Perhaps her most ambitious and visually arresting Grand Canyon project is the Desert View Watchtower (1932). Standing at the eastern edge of the South Rim, this towering stone structure is a marvel of engineering and design. Inspired by the ancient Anasazi watchtowers and kivas, Colter meticulously researched indigenous building techniques, even visiting ancient ruins to ensure authenticity. The 70-foot-tall tower is built of local stone, carefully laid to create the illusion of an ancient ruin, complete with "false" cracks and weathered surfaces. Inside, a circular staircase leads to various viewing platforms, while the walls are adorned with stunning murals by Hopi artist Fred Kabotie, depicting elements of Hopi mythology and daily life. The Watchtower is not just an observation point; it is a cultural monument, a testament to Colter’s profound respect for Native American heritage.

But Colter’s influence extended far beyond the Grand Canyon. Her most comprehensive work, and arguably her personal favorite, was La Posada (1930) in Winslow, Arizona. Conceived as a grand railway hotel and resort, La Posada was Colter’s magnum opus, a "total environment" where she designed everything from the architecture and interiors to the landscape, the furniture, the dishware, and even the staff uniforms. Blending Spanish Colonial Revival and Pueblo Revival styles, the hotel was envisioned as a sprawling, hacienda-like estate, with courtyards, gardens, and fountains. Each room was unique, adorned with hand-carved furniture, textiles, and art that evoked the rich history and culture of the Southwest. La Posada was a complete sensory experience, a living work of art that captured the romance of train travel and the mystique of the desert. Tragically, with the decline of rail travel, La Posada closed in 1957, falling into disrepair for decades before a miraculous restoration brought it back to its former glory in the late 1990s, allowing new generations to experience Colter’s unparalleled vision.

Colter’s work also included the charmingly rustic Phantom Ranch (1922), nestled at the bottom of the Grand Canyon, accessible only by mule or foot. Here, she designed simple stone and wood cabins that blended perfectly with the remote, rugged environment, providing weary travelers with a comfortable, yet authentically rustic, respite. Her touch was also evident in the opulent El Tovar Hotel (1905) (though not her primary design, she heavily influenced its interiors and subsequent renovations) and Bright Angel Lodge (1935), both at the Grand Canyon. At Bright Angel, she designed the famous "geological fireplace," a stunning creation built from layers of rock representing the different geological strata of the Grand Canyon, from the riverbed to the rim.

Mary Colter was not merely an architect; she was a demanding, meticulous, and often uncompromising artist. She had an unwavering vision and was known for her exacting standards, frequently clashing with contractors and even Fred Harvey Company executives to ensure her designs were executed precisely as intended. She was a petite woman in a male-dominated field, yet her fierce intellect, meticulous attention to detail, and profound understanding of her craft commanded respect. She personally supervised every aspect of construction, from the selection of individual stones to the placement of every piece of furniture. Her dedication to authenticity was legendary; she would insist on "distressing" new materials to give them an antique patina, a practice that initially baffled many but ultimately proved essential to her aesthetic.

By the time she retired in 1948, Mary Colter had reshaped the architectural landscape of the American Southwest, leaving behind a collection of buildings that are now cherished national treasures. Her work anticipated many principles of modern architecture, including organic design, contextualism, and a deep respect for local materials and cultural heritage. She was, in many ways, an early proponent of sustainable design, long before the term became commonplace, creating structures that were not only beautiful but also harmonious with their environment.

Mary Colter passed away in 1958 at the age of 88, but her spirit lives on in every stone, every beam, and every vista framed by her designs. Her buildings are more than just places to stay or visit; they are gateways to understanding the rugged beauty and rich history of the Southwest. They invite us to slow down, to observe, and to connect with the land in a profound and meaningful way. In an era when many structures are built for fleeting trends, Colter’s work stands as a timeless testament to the power of thoughtful design, a reminder that true artistry lies not just in what is built, but in how it makes us feel, and how it helps us see the world anew. Mary Colter didn’t just build hotels and rest stops; she built the soul of the Southwest, one meticulously crafted, perfectly placed stone at a time.