Mine Run: The Ghost of a Battle – Where the Civil War’s Future Was Nearly Forged and Then Forgotten

The late autumn air of rural Orange County, Virginia, often carries a hushed quality, a gentle rustle through the pine forests that belies the tumultuous history etched into its soil. Today, the landscape is one of quiet farms, winding country roads, and the occasional historical marker. Yet, beneath this serene surface lies the memory of a pivotal moment in the American Civil War – the Mine Run Campaign of November-December 1863. It was here that two of the greatest military minds of their era, Robert E. Lee and George G. Meade, squared off in a high-stakes chess match that, in the end, yielded no victor, but offered a stark preview of the brutal, entrenched warfare that would define the conflict’s final act.

Mine Run is not a name that resonates with the same thunder as Gettysburg or Antietam. It lacks the clear-cut heroism or tragic decisiveness that etches other battles into the national consciousness. Instead, it stands as a testament to the "what ifs" of history, a near-miss, a strategic stalemate born of caution, winter’s bite, and the burgeoning power of defensive entrenchments. Yet, to overlook Mine Run is to miss a crucial chapter in the war’s evolution, a campaign that profoundly influenced the tactics and morale of both armies and set the stage for Ulysses S. Grant’s relentless Overland Campaign the following spring.

The Weight of Expectation: Autumn 1863

By late 1863, the Union cause, though buoyed by victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg, still yearned for a decisive knockout blow against Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. President Abraham Lincoln, weary of the protracted struggle, pressed his generals for action. Major General George G. Meade, who had masterfully commanded the Army of the Potomac at Gettysburg, found himself under immense pressure. He had checked Lee’s invasion, but failed to destroy his army, a persistent frustration for Washington.

Lee, meanwhile, despite heavy losses, remained a formidable opponent. His smaller, leaner Army of Northern Virginia still held the Rapidan River line, a natural defensive barrier that guarded the approaches to Richmond. Morale among his troops, though tested, remained surprisingly resilient, fueled by their devotion to Lee and a fierce determination to protect their homeland.

Meade understood the strategic imperative. With winter approaching, a final offensive push was crucial before both armies settled into their winter quarters. His plan was bold: a rapid flanking maneuver, crossing the Rapidan east of Lee’s lines, aiming to get between the Confederates and Richmond. If successful, he could force Lee into a decisive open-field battle, or even trap him.

The Chess Match Begins: A Flanking Gambit

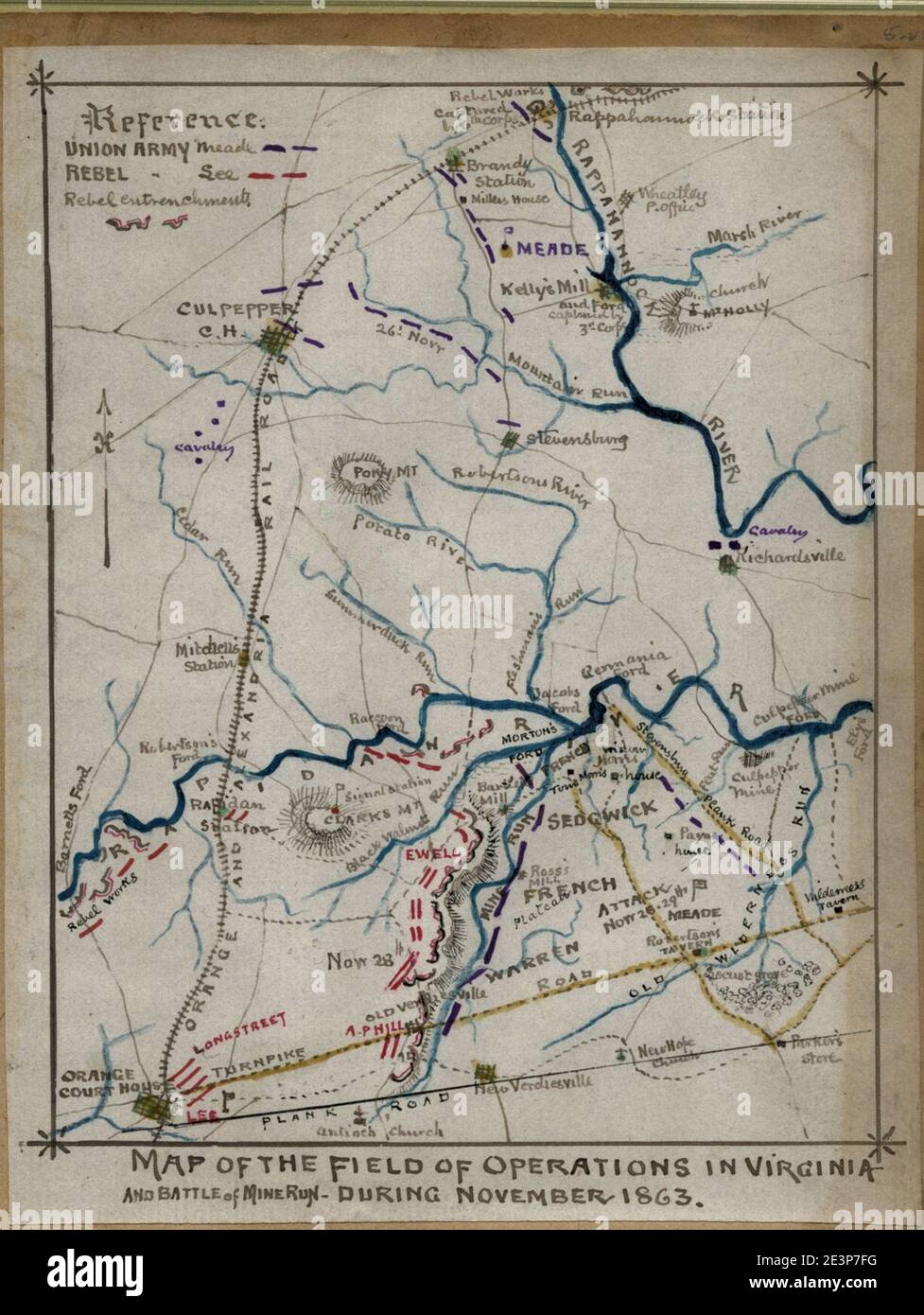

On November 26, 1863, the Army of the Potomac, some 80,000 strong, began its movement. In a series of rapid crossings, Union corps fanned out, aiming for various fords along the Rapidan. The initial movements were largely successful, catching elements of Lee’s army by surprise. For a brief, thrilling moment, it seemed Meade’s gamble might pay off.

However, Lee, ever the astute tactician, was not easily fooled. He quickly discerned Meade’s intentions and reacted with characteristic speed and precision. Abandoning his existing positions along the Rapidan, Lee ordered a rapid withdrawal and consolidation of his forces along the west bank of Mine Run, a small, meandering stream that offered a strong defensive line. This movement was a testament to the Confederate army’s mobility and their intimate knowledge of the terrain. "Lee’s ability to anticipate and counter Meade’s complex flanking movement was nothing short of brilliant," notes historian Dr. Amanda Peterson. "He turned what could have been a disaster into a strategic advantage, almost overnight."

As the Union columns pushed forward on November 27, they encountered not a retreating enemy, but a rapidly entrenching one. Skirmishes erupted, most notably at Payne’s Farm (also known as Locust Grove), where elements of Major General Gouverneur K. Warren’s II Corps clashed with Confederate units under Major General Edward Johnson. These were sharp, brutal fights, indicative of the ferocity that would have unfolded had a full battle commenced. They bought Lee precious time, allowing his engineers and soldiers to transform the Mine Run line into a formidable defensive barrier.

The Impenetrable Line: A Foreshadowing of the Future

By November 28, the Union army stood arrayed before the Confederate positions along Mine Run. What they saw chilled them to the bone. Lee’s men, using axes and shovels with incredible efficiency, had constructed a series of earthworks, rifle pits, and artillery redoubts that stretched for miles. The terrain itself, a mix of dense woods, ravines, and open fields, was naturally defensible, and the Confederates had maximized every advantage. Trees were felled to create abatis (a defensive obstacle made of sharpened branches), and fields were cleared to provide clear fields of fire.

Major General Gouverneur K. Warren, whose II Corps occupied the Union left flank, was ordered to probe the Confederate right. What he found was a nightmare: a strong, heavily entrenched line, well-manned and seemingly impregnable. Warren, a capable but cautious commander, reported back to Meade that an attack would be suicidal. His concerns were echoed by other corps commanders.

The Union high command faced a terrible dilemma. Their flanking maneuver had stalled. They had marched for days, endured skirmishes, and now stood before a seemingly unassailable enemy position. The weather, too, turned against them. The late November chill deepened into biting December cold. The ground began to freeze, and the days grew shorter, limiting opportunities for maneuver or attack. Soldiers on both sides shivered in their makeshift camps, the air thick with tension and the smell of woodsmoke.

A Chilling Indecision: The Unfought Battle

On November 30, Meade, after much deliberation, ordered a general assault for the following morning. He envisioned a coordinated attack: Warren’s corps on the left, supported by other elements, would launch the main offensive, while other corps made diversionary attacks. The plan was risky, bordering on desperate, but Meade felt he had little choice. To withdraw without striking a blow would be a profound blow to Union morale and a severe reprimand from Washington.

However, fate – or perhaps prudence – intervened. Warren, upon further reconnaissance, became convinced that an attack on his sector would be a catastrophe. He believed the Confederate lines were too strong, the approach too hazardous, and the cost in lives would be astronomical with little chance of success. In a dramatic move, he delayed his assault, then sent an urgent message to Meade, expressing his grave reservations and requesting permission to call off the attack.

Meade, facing the unanimous dissent of his corps commanders, and acutely aware of the potential for another Fredericksburg-like disaster, made the agonizing decision to cancel the assault. "It was the hardest decision of my military career," Meade later reportedly confided, though he publicly maintained, "I am perfectly satisfied that I could not have succeeded." Lee, waiting eagerly for the Union attack, was left bewildered when it never materialized. "The enemy has disappeared," he reportedly told his staff, almost disbelieving.

On the night of December 1-2, under the cover of darkness and a bitter cold, the Army of the Potomac began its withdrawal, retreating back across the Rapidan River to its winter quarters. The Mine Run Campaign was over.

The Legacy of Mine Run: A Glimpse into the Future

The immediate aftermath of Mine Run was one of frustration and disappointment for the Union. Lincoln was deeply disappointed, reportedly lamenting, "I greatly regret that Meade did not make the attack." Meade’s reputation, already scrutinized after Gettysburg, suffered further. The campaign was widely seen as a missed opportunity, a costly march that yielded nothing but exhaustion and a sense of anti-climax.

Yet, Mine Run’s significance runs far deeper than its immediate outcome. It was, in many ways, a dress rehearsal for the brutal, attrition-based warfare that would come to define the final year of the Civil War.

-

The Rise of Entrenchments: Mine Run unequivocally demonstrated the power of rapidly constructed field fortifications. Lee’s ability to transform an open landscape into an almost impregnable defensive line in a matter of days shocked the Union command. It showed that even a numerically superior force could be stalemated by well-entrenched defenders. This lesson was not lost on either side. When Grant launched his Overland Campaign in 1864, both armies would routinely dig in, creating a continuous line of trenches from the Wilderness to Petersburg. "Here, the war’s future was mapped out in mud and timber," states Civil War historian Dr. Liam O’Connell. "Mine Run was the laboratory where the tactics of trench warfare were perfected before they became the norm."

-

Meade’s Caution and Grant’s Arrival: Meade’s decision not to attack, though perhaps militarily sound, highlighted a fundamental difference in approach between him and the general who would soon take overall command of Union armies, Ulysses S. Grant. Grant, known for his relentless offensive spirit, might have pressed the attack, even at great cost. While Meade was a skilled tactician, he lacked the ruthless determination to accept massive casualties for a potentially decisive, if costly, victory. This strategic difference ultimately paved the way for Grant’s appointment as General-in-Chief in March 1864, with the Army of the Potomac serving as his main field army.

-

Lee’s Defensive Genius: For Lee, Mine Run was another testament to his defensive brilliance. Despite being outnumbered, he had outmaneuvered Meade, anticipated his moves, and forced him to back down without a major engagement. It was a strategic victory for the Confederacy, buying them precious time and preserving their army.

A Quiet Landscape, Loud with History

Today, the Mine Run battlefield remains largely preserved, thanks in part to the efforts of organizations like the American Battlefield Trust. Driving through the area, one can still see the undulations in the terrain where earthworks once stood, the dense woods that concealed troop movements, and the quiet streams that marked critical lines. There are no grand monuments or visitor centers like at Gettysburg, but the subtle power of the landscape is palpable.

Visiting Mine Run offers a unique perspective on the Civil War. It reminds us that history is not just about decisive victories and heroic charges, but also about the strategic gambles, the near misses, the chilling indecision, and the profound human cost of war. It is a place where the weight of command decisions, the terror of facing an unassailable foe, and the sheer physical hardship of a winter campaign become almost tangible.

The ghost of a battle, Mine Run whispers lessons about military evolution, the pressures of command, and the enduring resilience of those who fought on this ground. It stands as a silent sentinel, reminding us that even in the absence of a thundering clash, history was forged, and the future of a nation was irrevocably shaped. To understand Mine Run is to understand a crucial, often overlooked, chapter in the unfolding drama of the American Civil War, a chapter that laid the groundwork for the ultimate, bloody resolution.