The Unseen Epidemic: Confronting the Crisis of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women

A shadow falls across Indigenous communities in North America, a pervasive and often unacknowledged crisis that has stolen mothers, daughters, sisters, and grandmothers from their families and futures. It is the epidemic of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW), a systemic failure that has left countless cases unsolved, families devastated, and a deep scar on the collective conscience. Far from a collection of isolated incidents, the MMIW crisis is a direct lineage of historical injustices, rooted in colonialism, systemic racism, and a complex web of jurisdictional challenges that often leave Indigenous women and girls vulnerable and their cases dismissed.

For decades, the stories of missing and murdered Indigenous women were whispered within communities, a heartbreaking reality often ignored by mainstream media and law enforcement. The lack of comprehensive data is, in itself, a testament to this neglect. However, recent grassroots activism and dedicated research have begun to pull back the veil, revealing a staggering disparity.

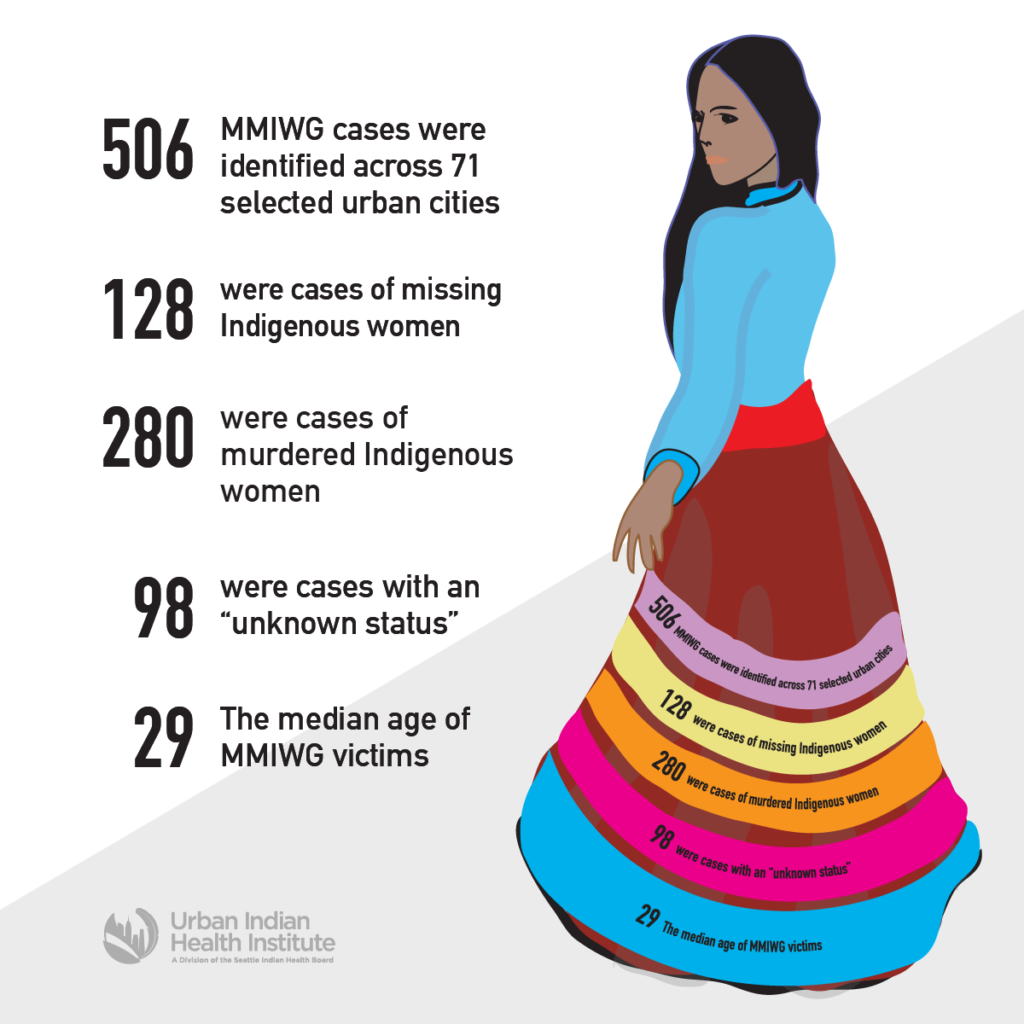

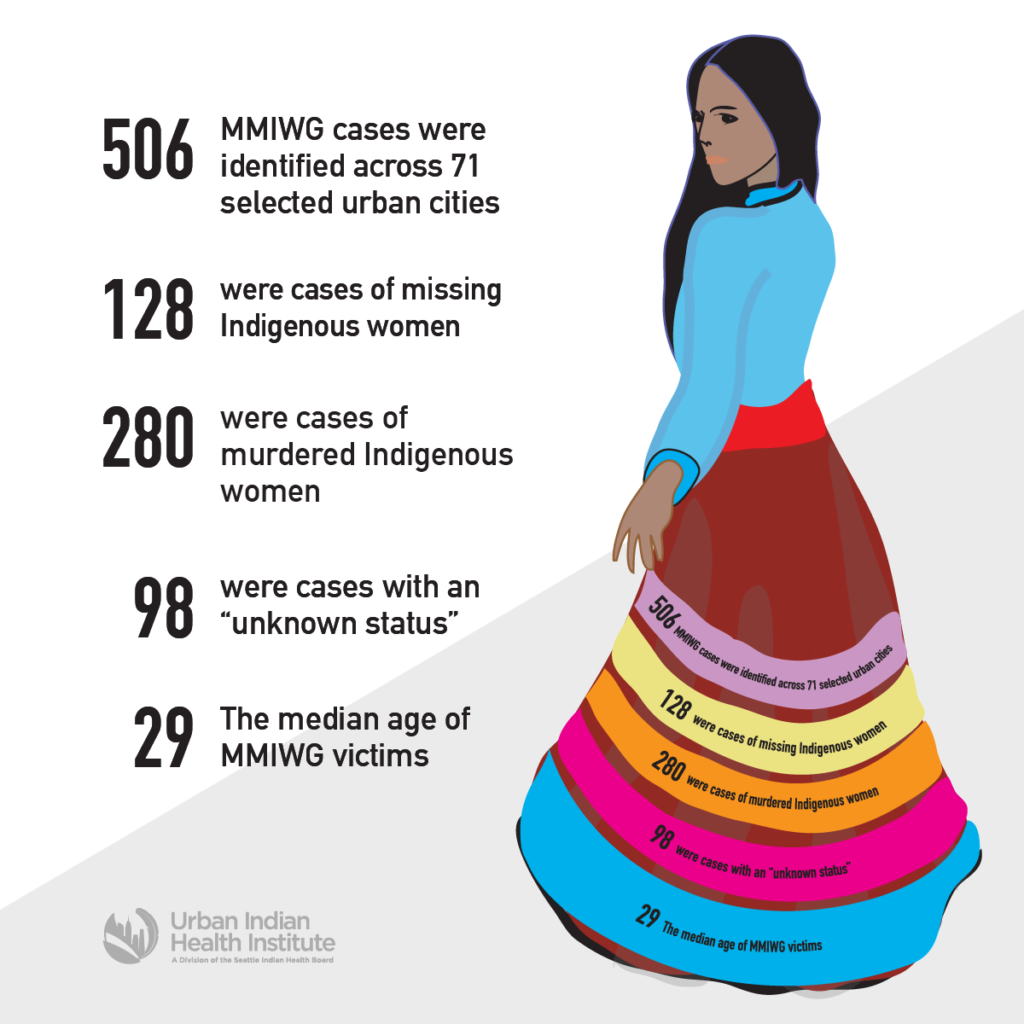

According to a 2016 study by the National Institute of Justice (NIJ), more than four out of five Indigenous women (84.3%) have experienced violence in their lifetime, with more than half (56.1%) experiencing sexual violence. On some reservations, Indigenous women are murdered at a rate ten times higher than the national average. A groundbreaking 2018 report by the Urban Indian Health Institute (UIHI) identified 5,712 cases of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls in 2016 alone, yet only 116 were logged in the U.S. Department of Justice’s federal missing persons database. These numbers, while horrifying, are widely considered to be vast undercounts due to inconsistent data collection, misclassification of cases, and jurisdictional complexities. The true scope of the crisis remains largely unknown, an abyss of uncounted lives.

The roots of the MMIW crisis are deeply embedded in the historical trauma inflicted upon Indigenous peoples. Centuries of colonization, forced assimilation, the residential school system, and the systematic dismantling of tribal governance have created conditions of extreme vulnerability. These historical policies led to intergenerational trauma, poverty, substance abuse, and a breakdown of traditional family structures, leaving communities ill-equipped to protect their most vulnerable members.

Furthermore, the very legal frameworks designed to provide justice often fail Indigenous victims. The "jurisdictional maze" is a critical impediment. On tribal lands, criminal jurisdiction is often fragmented. Tribal courts have limited authority over non-Native perpetrators, even when crimes occur on their own territory. If a non-Native person commits a crime against an Indigenous person on a reservation, the case often falls to federal authorities, who may lack the resources, understanding, or willingness to thoroughly investigate. State law enforcement agencies may also be involved, adding another layer of complexity. This patchwork of authority creates gaps where cases can fall through the cracks, investigations stall, and perpetrators walk free.

"The jurisdictional complexities are a nightmare," explains Deb Haaland, the first Native American U.S. Secretary of the Interior, whose department oversees tribal relations. "When a Native woman goes missing or is murdered, it’s often unclear who has the authority to investigate – tribal police, federal agents, or state law enforcement. This confusion leads to delays, miscommunication, and ultimately, justice denied." This bureaucratic labyrinth is a key reason why so many cases remain unsolved and why a sense of impunity often surrounds violence against Indigenous women.

Adding to this vulnerability is the proliferation of "man camps" – temporary housing for transient, often male, workers associated with resource extraction industries like oil, gas, and mining. These camps, frequently located near or on reservation borders, have been linked to significant increases in violent crime, including sexual assault, against Indigenous women in surrounding communities. The influx of a large, predominantly male, non-Native workforce into rural areas with limited law enforcement resources and pre-existing social vulnerabilities creates a dangerous environment where violence often goes unreported or unprosecuted.

Systemic failures extend beyond jurisdiction. Law enforcement agencies, both federal and local, have historically been criticized for their inadequate response to MMIW cases. This includes a lack of cultural competency, implicit bias against Indigenous victims, dismissiveness of reports, and a failure to allocate sufficient resources for investigations. Families often report being met with indifference, their pleas for help dismissed, and their loved ones categorized as runaways or addicts, rather than victims of serious crime. This deep-seated distrust in the justice system further exacerbates the problem, leading to underreporting and a sense of hopelessness within communities.

The media’s role has also been critically examined. For years, MMIW cases received scant attention from mainstream news outlets, a stark contrast to the widespread coverage given to missing non-Indigenous women. When cases were reported, they often perpetuated harmful stereotypes, focusing on victims’ perceived vulnerabilities rather than the crimes committed against them. This lack of visibility contributed to the public’s ignorance of the crisis and reinforced the idea that Indigenous lives hold less value. As one advocate poignantly stated, "Our women go missing in plain sight, but no one is looking."

The human cost of the MMIW crisis is immeasurable. Each missing or murdered woman leaves behind a devastated family and a traumatized community. The constant fear, the unanswered questions, and the lack of closure erode trust, perpetuating cycles of grief and intergenerational trauma. These women are not just statistics; they are vital members of their communities, keepers of culture, language, and tradition. Their loss diminishes everyone. The void left by a missing mother, a stolen daughter, or a murdered sister ripples through generations, affecting the social fabric, spiritual well-being, and cultural continuity of Indigenous nations.

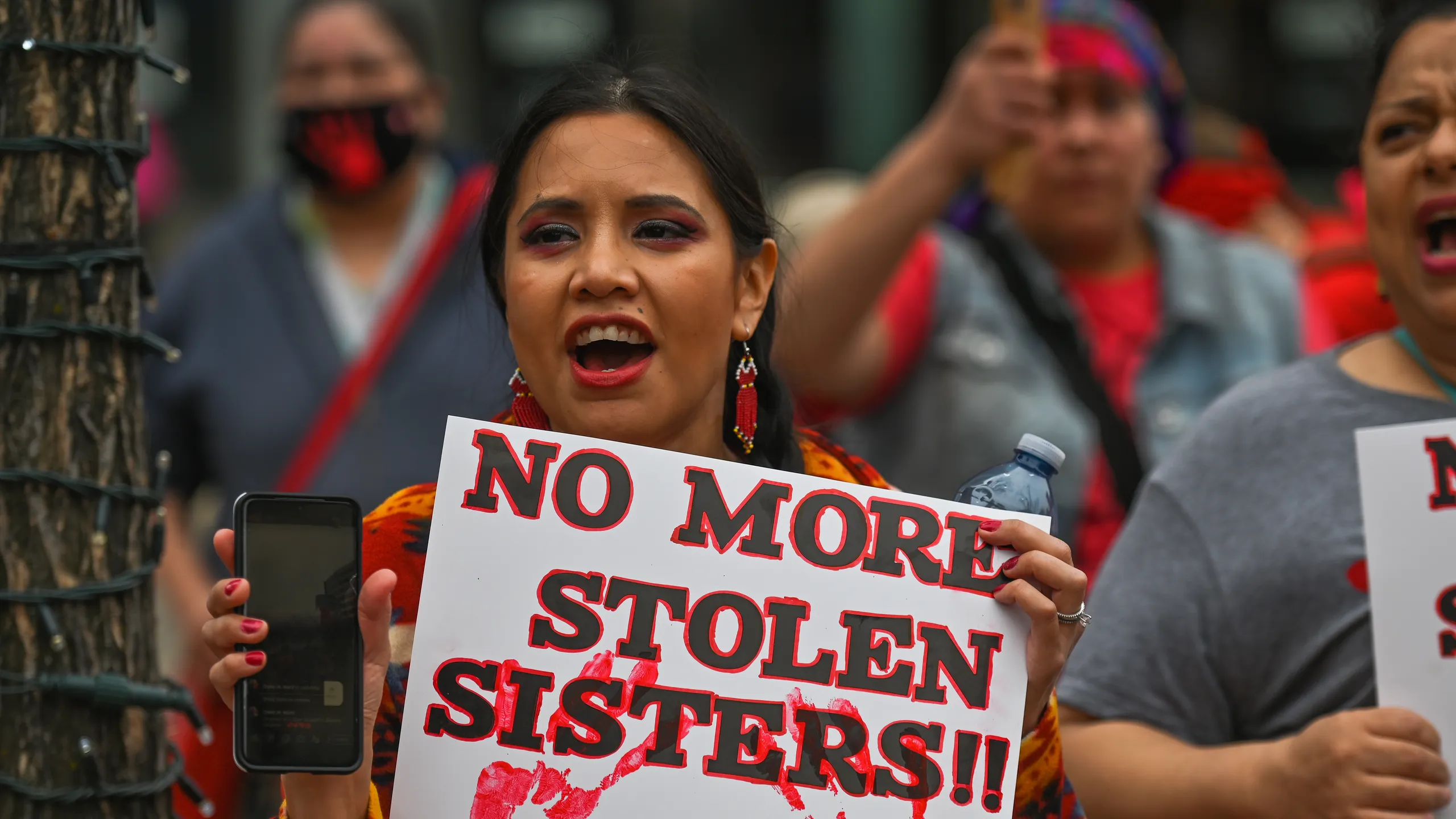

In the face of such overwhelming challenges, a powerful movement has emerged. Indigenous communities, families, and allies have taken up the mantle, organizing grassroots efforts to raise awareness, support victims’ families, and demand justice. The iconic red handprint over the mouth, symbolizing the silenced voices of Indigenous women, has become a potent international symbol of the MMIW movement. Social media campaigns, awareness walks, and advocacy efforts have brought the crisis into the public consciousness, forcing policymakers to confront what was once ignored.

These efforts have begun to yield results. In the United States, significant legislative steps have been taken. Savanna’s Act, signed into law in 2020, aims to improve data collection and coordination among law enforcement agencies in MMIW cases. Named after Savanna LaFontaine-Greywind, a pregnant 22-year-old Spirit Lake Nation citizen who was murdered in North Dakota, the act requires standardized protocols for responding to MMIW cases. The Not Invisible Act, also signed into law in 2020, established a joint commission of federal and non-federal experts to make recommendations to the Department of Justice and Department of Interior on how to combat the crisis. These acts, while not a panacea, represent crucial steps toward addressing the systemic failures that have allowed the crisis to persist.

Beyond legislation, there is a growing call for increased funding for tribal law enforcement, improved training on cultural sensitivity for all police officers, and greater collaboration between tribal, state, and federal agencies. Empowering tribal nations with greater jurisdictional authority over crimes committed on their lands is also seen as a vital step towards ensuring justice for their citizens. The movement emphasizes that true progress requires not only addressing the symptoms of the crisis but also dismantling the colonial structures and systemic racism that underpin it.

The crisis of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women is more than a tragic statistic; it is a profound human rights failure that demands immediate and sustained action. It is a stark reminder that justice is not blind when it comes to race and jurisdiction. Addressing this epidemic requires a holistic approach: acknowledging historical wrongs, investing in Indigenous communities, strengthening tribal sovereignty, reforming law enforcement practices, and ensuring that every missing Indigenous woman and girl receives the same urgency and attention as any other. Only then can the shadow begin to lift, and healing truly begin for the communities that have borne this unbearable burden for far too long.