My Dinner with Samuel Adams: An Evening at the Cradle of Liberty

BOSTON, Massachusetts Bay Colony – The summons arrived, not with the fanfare of a royal decree, but with the quiet urgency of a whispered secret. A folded parchment, delivered by a solemn-faced young man, bore a simple invitation: "Mr. Adams requests your presence this eve at the Green Dragon Tavern, for a matter of pressing import." My heart quickened. Samuel Adams. The very name was a lightning rod in these tumultuous times, a beacon for some, a menace for others. As a nascent journalist, keen to chronicle the pulse of this rebellious colony, the opportunity to sit with the architect of its discontent was too invaluable to refuse.

It was a blustery evening in late autumn of 1774, the kind that carried the salty tang of the harbor and the scent of woodsmoke through the narrow, cobbled streets of Boston. Tensions, thick as the fog that often blanketed the town, hung heavy in the air. The Boston Tea Party, barely a year prior, still resonated like a thunderclap, and the British response – the Coercive Acts, or "Intolerable Acts" as the colonists defiantly called them – had only stoked the fires of defiance. Soldiers in their scarlet coats patrolled with an air of arrogant authority, their presence a constant, grating reminder of imperial oversight.

The Green Dragon Tavern, nestled in the North End, was more than just an alehouse; it was the unofficial parliament of the Revolution. Known as the "Cradle of Liberty," its low-ceilinged rooms had witnessed countless clandestine meetings, fiery debates, and the forging of revolutionary resolve. As I pushed open the heavy wooden door, a wave of warmth, mingled with the aroma of roasted meat, stale ale, and damp wool, washed over me. The air was thick with the murmur of voices, the clatter of tankards, and the occasional burst of raucous laughter. But beneath the convivial din, there was an undercurrent of serious purpose, a sense of men gathered not merely for drink, but for destiny.

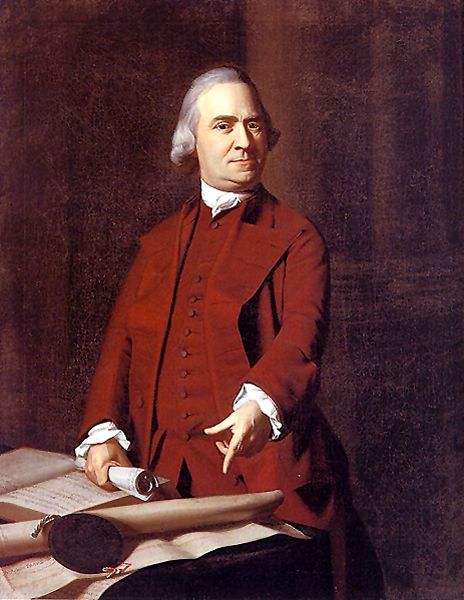

I spotted him immediately, not because he commanded attention with a booming voice or an imposing stature, but because he was precisely where I expected him to be: tucked away in a dimly lit corner booth, away from the boisterous main room. Samuel Adams. He was not the towering figure I might have imagined, nor the charismatic orator that some of his contemporaries, like John Hancock, were. Instead, he was a man of modest height, dressed in plain, unadorned clothes that spoke of frugality rather than fashion. His periwig, if he wore one, was certainly not powdered, and his face, though marked by the passage of fifty-two years, was sharp and intelligent.

What struck me most were his eyes. They were a piercing blue, watchful and intense, betraying a mind constantly at work, perpetually dissecting, strategizing, and envisioning. There was an almost puritanical austerity about him, a solemn dedication that seemed to consume his very being. As I approached, he offered a slight, almost imperceptible nod, indicating the seat opposite him. "You are prompt, Mr. [Your Name]," he said, his voice a low, gravelly tone, devoid of affectation. "A quality I much appreciate in these uncertain times."

The table between us was simple, set with pewter plates and tankards. A steaming bowl of beef stew, thick with root vegetables, sat at its center, alongside a loaf of crusty bread. The meal, like the man, was unpretentious, hearty, and functional. "Eat, Mr. [Your Name]," he urged, gesturing with a calloused hand. "A full belly clears the mind, and we have much to discuss."

Our initial conversation was cautious, a dance of probing questions and measured answers. I, the eager chronicler, sought to understand the man who had, more than any other, relentlessly stoked the embers of colonial discontent into a raging inferno. He, the seasoned revolutionary, seemed to be assessing my resolve, my understanding of the stakes.

"Mr. Adams," I began, scooping a generous portion of stew onto my plate, "many call you the chief instigator of this unrest. They say you seek only to sow discord with the Crown."

He took a slow sip of his ale, his gaze fixed on some distant point beyond the tavern walls. "Discord?" he mused, a faint, almost imperceptible flicker of a smile touching his lips. "Perhaps. But one must first define what discord truly is. Is it discord to demand the ancient rights of Englishmen? Is it discord to resist the encroachment of tyranny upon a free people?" He paused, then turned his piercing gaze directly upon me. "No, Mr. [Your Name]. We seek not discord, but liberty. We seek to restore the harmony that has been shattered by a Parliament that believes itself above the very laws it purports to uphold."

His words were not fiery oratory, but rather the quiet, unwavering conviction of a man who had pondered these principles for decades. He spoke of natural rights, of self-governance, and of the fundamental injustice of taxation without representation. "The power to tax," he asserted, leaning slightly forward, his voice gaining a quiet intensity, "is the power to destroy. If we allow Parliament to take our property without our consent, what then remains of our freedom? We become no more than slaves, subject to the whims of masters across an ocean."

It was a sentiment I had heard before, but from Adams’s lips, it carried an almost sacred weight. He wasn’t merely repeating a slogan; he believed it, with every fiber of his being. He wasn’t a man driven by ambition or personal gain; his own life, perpetually teetering on the edge of financial ruin, was testament to that. He was driven by an unshakeable adherence to principle, a puritanical zeal for what he perceived as God-given liberty.

Our conversation turned to the methods of resistance. Adams, I learned, was a master of organization and propaganda. He spoke with pride of the Committees of Correspondence, the network he had tirelessly built, connecting towns and colonies, ensuring that news of British transgressions spread like wildfire. "Information, Mr. [Your Name]," he explained, "is the lifeblood of revolution. Without it, the people remain ignorant, complacent. We must educate them, awaken them to the chains being forged for them."

He detailed his use of pseudonymous essays in newspapers, shaping public opinion, dissecting ministerial policies with surgical precision. "The pen," he declared, "is a mighty sword in this conflict. It can pierce the armor of indifference and ignite the flame of patriotism where none existed before." It became clear that Adams understood the power of public opinion perhaps better than any other revolutionary figure. He knew that the war would not be won solely on battlefields, but in the minds and hearts of ordinary citizens.

As the evening wore on, and the tavern emptied around us, Adams’s focus never wavered. He spoke of the increasing likelihood of open conflict, not with relish, but with a grim determination. "The British," he stated, his voice now lower, more serious, "have made their choice. They seek to subdue us by force, to crush our spirit. We have but one choice in return: to resist, to stand firm, even if it means the ultimate sacrifice."

I ventured to ask about the personal cost, the risk of treason. He met my gaze squarely. "The liberties of our country, the freedom of our civil constitution," he said, his voice resonating with an almost prophetic certainty, "are worth defending at all hazards. It is a debt we owe to our posterity, and to the God who gave us these rights. If we are not prepared to die for them, we shall surely lose them."

He wasn’t a man given to grand pronouncements or emotional displays, but in that moment, the depth of his conviction was palpable. It was not a call for reckless abandon, but a somber acceptance of the dire necessity of the moment. He seemed to embody the spirit of the oft-quoted maxim (though not his own words, they resonated with his philosophy): "It does not require a majority to prevail, but rather an irate, tireless minority keen to set brushfires of freedom in the minds of men." Adams was that tireless minority, relentless in his pursuit of liberty.

As the embers in the tavern’s hearth faded to a dull glow, and the silence of the late hour settled around us, Adams rose. His movements were deliberate, unhurried. "The hour grows late, Mr. [Your Name]," he said, "and much work remains to be done. For both of us." He extended a hand, his grip firm and dry. "Remember what you have witnessed here tonight. Remember the cause for which we strive. The eyes of the world, and indeed, of future generations, are upon us."

Stepping back out into the cold Boston night, the air felt sharper, the distant sounds of the sentries’ boots on the cobblestones more ominous. Yet, I also felt a profound sense of clarity. My dinner with Samuel Adams was not a meal of pleasantries, but a communion with the very soul of the burgeoning revolution. He was not a man of charisma in the conventional sense, but a formidable force of unwavering principle and relentless action.

Samuel Adams, the "Penman of the Revolution," was no orator like Patrick Henry, no philosopher like Jefferson, no general like Washington, nor a statesman like Franklin. He was, fundamentally, an agitator, an organizer, a tireless advocate who understood the power of ideas and the necessity of popular mobilization. He was the vital, often overlooked, cog in the revolutionary machine, the man who laid the groundwork for the Declaration of Independence by systematically dismantling the psychological hold of the British Crown over the colonial mind.

That night, in the humble setting of the Green Dragon Tavern, I had not merely shared a meal with a historical figure; I had touched the very essence of American liberty, distilled through the unwavering resolve of a man who truly believed that freedom was not given, but eternally fought for. His quiet intensity, his deep conviction, and his unyielding dedication to principle left an indelible mark, reaffirming my own understanding that the seeds of revolution were not sown by grand gestures, but by the relentless, principled efforts of individuals like Samuel Adams. And as the dawn of independence broke over the horizon, it was men like him, tirelessly working in the shadows, who had ensured that when the call to arms came, the American people were ready to answer.