Echoes of the Ancestors: Exploring Native American Funeral Rites and Beliefs

Death, the ultimate equalizer, is a universal experience, yet its interpretation and the rituals surrounding it vary profoundly across cultures. For the myriad of Indigenous nations of North America, the transition from life to the spirit world is not an end but a profound transformation, deeply interwoven with their holistic worldview, reverence for nature, and an enduring connection to their ancestors. Far from a monolithic set of practices, Native American funeral rites and beliefs are as diverse and rich as the hundreds of distinct nations themselves, each with unique traditions, but often united by core philosophical tenets.

This article delves into the profound and diverse funeral rites and beliefs of Native Americans, exploring the underlying spiritual philosophies, the intricate ceremonies that guide the departed, and the enduring resilience of these traditions in the face of historical adversity.

The Interconnected Web: Core Beliefs

At the heart of most Native American spiritual traditions lies the concept of interconnectedness – that all living things, the earth, the sky, and the spirit world are part of a single, interdependent web. This philosophy, often encapsulated in the Lakota phrase "Mitakuye Oyasin" ("All My Relations"), extends to the understanding of death. Death is not seen as a finality, but rather a cyclical movement, a return to the source, or a journey to another realm of existence.

The spirit is generally believed to be immortal, capable of continuing its journey beyond the physical body. This journey often involves a period of transition, during which the spirit may linger near loved ones, travel to a specific spiritual homeland, or ascend to the stars. The purpose of many funeral rites is to assist the deceased’s spirit on this journey, to ensure its peaceful passage, and to protect the living from any potential negative influences of a restless spirit.

The Sacred Journey: Preparing for Transition

The rituals surrounding death typically begin immediately after a person’s passing, focusing on preparing the body and guiding the spirit. These preparations vary widely:

- Cleansing and Dressing: The body is often ritually cleansed, sometimes with sacred herbs or water, and dressed in traditional attire or special burial garments. Personal effects, symbolic items like feathers, beads, or tobacco, might be placed with the deceased to aid their journey or signify their status. For some Plains tribes, a favorite horse might even be sacrificed to accompany the deceased.

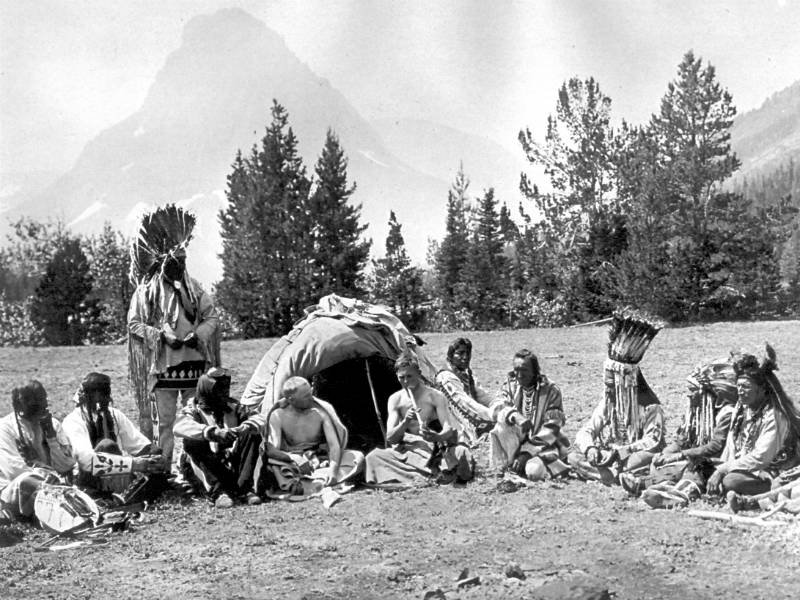

- Vigils and Wakes: Many nations hold extended wakes or vigils, lasting several days and nights. These are not merely periods of mourning but communal gatherings where family and friends share stories, sing sacred songs, pray, and offer comfort. These gatherings reinforce community bonds and allow for collective grieving and support. The Navajo, for instance, hold a four-day ceremony to guide the spirit and ensure it does not linger, involving specific songs and prayers.

Diverse Dispositions: From Earth to Sky

The method of disposing of the body is highly culturally specific, reflecting the relationship with the land and the spirit world.

- Earth Burial: The most prevalent form, earth burial, emphasizes the return of the body to Mother Earth, completing the natural cycle. Graves are often shallow, and the body might be placed in a fetal position, symbolizing rebirth, or facing a specific direction, like the rising sun, signifying new beginnings or the path of the spirit. Sacred objects, food, or tools might be buried with the deceased to sustain them on their journey.

- Scaffold and Tree Burial: For many Plains tribes, like the Lakota and Cheyenne, scaffold or tree burial was practiced. The body, wrapped in blankets or hides, would be placed on a raised platform or in the branches of a tree. This elevated position was believed to bring the deceased closer to the Sky World and allow their spirit to easily depart. It also prevented desecration by animals and allowed for natural decomposition, with the bones later collected and buried.

- Cremation: While less common historically than burial, some tribes, particularly in the Pacific Northwest, practiced cremation. This was often seen as a way to quickly release the spirit from the body, preventing it from lingering. The ashes would then be scattered in sacred places or kept in special containers.

- Spirit Houses: Some tribes, such as the Ojibwe, constructed small "spirit houses" over graves, providing a symbolic dwelling for the deceased’s spirit and a place for offerings.

The Afterlife: A Place of Peace and Reunion

Beliefs about the afterlife vary, but they generally envision a place of peace, reunion, and continued existence.

- The Spirit Road: Many tribes believe in a "Spirit Road" or "Milky Way" that the deceased’s spirit travels to reach its final destination. For the Lakota, this is the "Wichankpe Oyate," the Star Nation, where ancestors reside.

- Reunion with Ancestors: A common and comforting belief is that the deceased will be reunited with their ancestors in the spirit world, a place of harmony and abundance. This reinforces the continuous lineage and the idea that the living are merely one part of a vast, ongoing family extending into the past and future.

- Continued Presence: Some traditions hold that the spirits of the deceased can remain connected to the living, offering guidance or protection, particularly during ceremonies or in times of need. However, other traditions, like some Navajo beliefs, emphasize the need for the spirit to move on completely, and certain precautions are taken to avoid the lingering presence of "ch’íídii" (ghosts).

Grief, Community, and Healing

Mourning periods are often structured and communal. Grief is seen as a natural process, but one that is managed with the support of the community.

- Communal Support: The community plays a vital role in supporting the grieving family, providing food, comfort, and participating in ceremonies. This collective burden-sharing underscores the importance of community in Indigenous societies.

- Ceremonial Mourning: Depending on the tribe, specific mourning rituals may involve cutting hair, wearing special clothing, or abstaining from certain activities for a prescribed period. For some, elaborate feasts or potlatches are held, not just to honor the dead, but also to redistribute wealth and demonstrate the family’s generosity, reinforcing social ties and status.

- Healing Ceremonies: After the initial mourning period, many tribes conduct ceremonies aimed at helping the living heal and re-enter daily life. These might involve purification rites, sweat lodge ceremonies, or specific dances and songs designed to bring closure and restore balance. The goal is not to forget the deceased, but to integrate their memory into the ongoing life of the community in a healthy way.

Enduring Wisdom in a Changing World

Centuries of colonization, forced assimilation, and the suppression of Indigenous cultures severely impacted traditional funeral rites. The imposition of Christian burial practices, the removal of children to boarding schools, and the prohibition of ceremonies led to the loss of many practices and the fragmentation of knowledge.

However, the resilience of Native American cultures is a powerful testament to their enduring spirit. Today, there is a powerful resurgence of interest in and revitalization of traditional funeral rites and beliefs. Tribal communities are actively reclaiming their ancestral practices, teaching younger generations the sacred songs, languages, and ceremonies associated with death.

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) of 1990 in the United States has been crucial in this revitalization, facilitating the return of ancestral remains and sacred objects from museums and institutions to their rightful tribal communities for reburial according to traditional customs. This act acknowledges the deep spiritual connection Indigenous peoples have to their ancestors and the land.

In conclusion, Native American funeral rites and beliefs offer a profound perspective on life, death, and the continuum of existence. They are more than mere rituals; they are intricate expressions of a worldview that honors interconnectedness, reveres nature, and acknowledges the immortal journey of the spirit. In a world grappling with mortality, the wisdom embedded in these ancient traditions — of communal support, spiritual passage, and the enduring bond between the living and the ancestors — resonates with timeless relevance, reminding us that even in death, life’s sacred cycle continues, echoing the wisdom of generations past into the future.