Bones of Contention, Seeds of Reconciliation: NAGPRA’s Transformative Power

For generations, the bones of Native American ancestors lay not in sacred ground, but in museum drawers. Their funerary objects, tools, and sacred regalia, intended for passage into the spirit world, were instead cataloged and displayed behind glass, silent testaments to a history of conquest and cultural appropriation. This deeply unsettling reality, a lingering wound from centuries of colonialism, began to find its healing balm with the passage of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) in 1990.

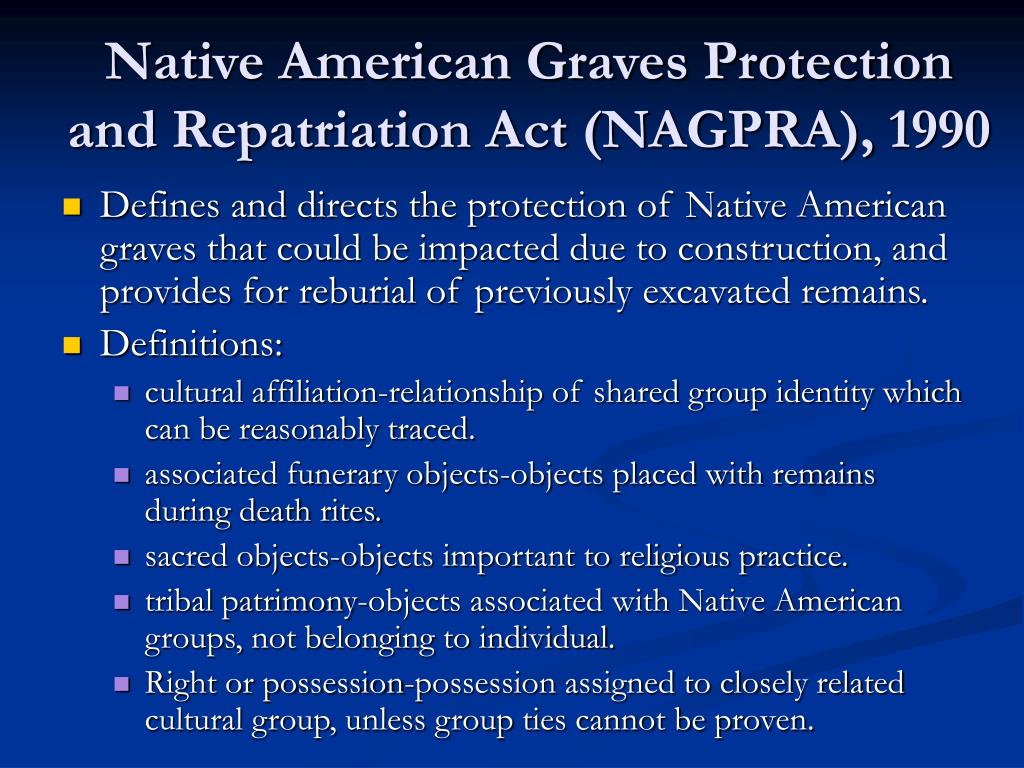

NAGPRA, a landmark piece of federal legislation, fundamentally shifted the paradigm of ownership and stewardship over Native American human remains and cultural items. It mandated that federal agencies and museums receiving federal funds inventory their collections and, upon request, repatriate these items to lineal descendants, culturally affiliated Native American tribes, or Native Hawaiian organizations. More than just a legal framework, NAGPRA has become a powerful, albeit often arduous, vehicle for justice, reconciliation, and the restoration of dignity to America’s Indigenous peoples.

A Legacy Unearthed: The Pre-NAGPRA Landscape

To understand the profound necessity of NAGPRA, one must grasp the historical context it sought to rectify. For much of the 19th and 20th centuries, archaeological and anthropological practices, often intertwined with a colonial mindset, prioritized scientific collection over respect for Indigenous cultures. Grave sites were routinely excavated without tribal consent, human remains were considered "specimens" for study, and sacred objects were seized or purchased under duress, then proudly exhibited in institutions across the country and the world.

Estimates suggest that by the late 1980s, over 200,000 Native American human remains were housed in federal repositories and museums. The Smithsonian Institution alone held an estimated 18,600 sets of human remains, with countless more funerary objects, sacred artifacts, and objects of cultural patrimony. This vast accumulation was not merely academic; it was deeply dehumanizing. For Native communities, the ancestors’ bones were not just biological material; they were relatives, their spirits denied proper rest, their journeys to the afterlife interrupted. The removal of sacred objects severed vital spiritual connections, impacting ceremonies, traditional knowledge, and cultural continuity.

"Our ancestors were being treated like curiosities, like scientific objects," remarked Walter Echo-Hawk, a Pawnee attorney and a key figure in the legal efforts leading up to NAGPRA. "Their sacred resting places desecrated, their spirits restless. This was not just a legal issue; it was a spiritual crisis."

Growing activism from Native American communities throughout the 20th century, coupled with increasing public awareness and evolving ethical standards within the museum and academic communities, created the momentum for legislative change. Years of lobbying, protests, and emotional testimony culminated in the passage of NAGPRA, signed into law by President George H.W. Bush on November 16, 1990.

The Law’s Core Pillars: A Framework for Return

At its heart, NAGPRA addresses five distinct categories of cultural items:

- Human Remains: The physical remains of Native American individuals.

- Associated Funerary Objects: Objects placed with human remains at the time of burial or death.

- Unassociated Funerary Objects: Objects separated from human remains but clearly made for burial or as part of a death rite.

- Sacred Objects: Items needed for the practice of traditional Native American religions.

- Objects of Cultural Patrimony: Items with ongoing historical, traditional, or cultural importance central to a Native American group, which cannot be alienated by any individual.

The law requires museums and federal agencies to:

- Inventory: Compile detailed inventories of human remains and associated funerary objects.

- Summarize: Create summaries of unassociated funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony.

- Consult: Engage in good-faith consultation with lineal descendants and Native American tribes or Native Hawaiian organizations to determine cultural affiliation.

- Repatriate: Upon receiving a valid claim and demonstrating cultural affiliation, return these items.

- Protect: Prohibit the trafficking of Native American human remains and cultural items. It also establishes procedures for the intentional excavation or inadvertent discovery of Native American cultural items on federal or tribal lands.

A crucial component of NAGPRA is the NAGPRA Review Committee, a seven-member advisory body that monitors the implementation of the law, mediates disputes, and makes recommendations to Congress. This committee plays a vital role in navigating the complex landscape of cultural affiliation and competing claims.

Transformative Impact: Healing and Reconciliation

The impact of NAGPRA has been profound, extending far beyond mere legal compliance. It has fostered a radical shift in the relationship between Native American tribes and institutions that once held their heritage captive.

One of the most high-profile cases illustrating NAGPRA’s power was the repatriation of the "Ancient One," also known as Kennewick Man. Discovered in 1996, these 9,000-year-old remains became the subject of a contentious legal battle between scientists, who sought to study them for insights into early American populations, and a coalition of Columbia River Basin tribes, who asserted their cultural affiliation and right to rebury their ancestor. After decades of legal wrangling, scientific studies, and legislative intervention, the Ancient One was finally repatriated to the tribes in 2017 and reburied in a secret location, bringing a measure of closure to a deeply painful chapter.

While not all repatriations garner such media attention, thousands of ancestral remains and hundreds of thousands of cultural objects have been returned to their rightful communities. As of 2023, the National Park Service, which oversees NAGPRA, reported that over 200,000 sets of human remains and millions of associated funerary objects had been inventoried, with tens of thousands of remains and hundreds of thousands of objects either repatriated or available for repatriation.

For tribal nations, each repatriation is a moment of profound spiritual and cultural healing. "When our ancestors come home, it’s like a missing piece of our soul returns," shared a representative from the Pawnee Nation during a repatriation ceremony. "It strengthens our identity, reconnects us to our traditions, and affirms our inherent sovereignty." This process allows for proper reburial ceremonies, the reincorporation of sacred objects into spiritual practices, and the revitalization of traditional knowledge systems that were suppressed or lost.

Museums and universities, initially resistant in some cases, have largely adapted, transforming their roles from possessors to partners. Many institutions now actively collaborate with tribes, developing ethical guidelines for future research, and engaging in respectful consultation processes. This shift has led to a more nuanced understanding of Indigenous cultures and a greater appreciation for the importance of cultural heritage protection.

Challenges and the Road Ahead

Despite its successes, NAGPRA’s implementation has not been without significant challenges. The process is often slow, complex, and resource-intensive for both tribes and institutions.

- Pace of Repatriation: While substantial progress has been made, tens of thousands of human remains and countless objects remain in institutional collections, often due to lack of funding, unclear cultural affiliation, or ongoing disputes. The sheer volume of items, coupled with the meticulous research and consultation required, means that repatriation is an ongoing, multi-generational endeavor.

- Funding: Tribes often lack the resources for extensive archival research, travel for consultations, and proper reburial ceremonies. Similarly, museums, particularly smaller ones, may struggle with the costs associated with inventorying, storage, and the repatriation process itself.

- "Culturally Unidentifiable" Remains: One of the most contentious issues revolves around human remains that cannot be definitively linked to a modern-day federally recognized tribe. While regulations have evolved to encourage the repatriation of these remains to Indigenous groups with a strong geographical or cultural connection, they remain a significant portion of unreturned ancestors, perpetuating a painful limbo for many communities.

- Definition Disputes: The interpretation of terms like "sacred objects" and "objects of cultural patrimony" can lead to disagreements, requiring mediation or legal intervention.

- International Scope: NAGPRA only applies to federal agencies and institutions receiving federal funds within the United States. Vast collections of Native American cultural heritage remain in museums and private hands abroad, outside the scope of U.S. law, presenting a new frontier for repatriation efforts.

- Ongoing Looting: Despite NAGPRA’s prohibitions, the illicit trade in Native American artifacts continues, driven by a lucrative black market that undermines the spirit of the law and desecrates ancestral lands.

Looking forward, the journey of repatriation under NAGPRA continues. Advocates emphasize the need for sustained federal funding, clearer guidelines for "culturally unidentifiable" remains, and increased education for both the public and institutions about the law’s intent and importance. There’s also a growing movement for more collaborative archaeology, where tribes are partners from the outset, guiding research and ensuring cultural sensitivity.

NAGPRA is more than a law; it is a living testament to resilience, a commitment to righting historical wrongs, and a powerful tool for cultural revitalization. It acknowledges that the past is not merely history to be studied, but a living presence that shapes the present and informs the future. As Native American ancestors and their sacred belongings continue their journey home, each return marks another step towards healing, reconciliation, and a more just and respectful relationship between all peoples on this land. The dust of museum shelves is slowly giving way to the dignity of reburial, ensuring that the spirits of the past can finally rest, and the cultures of the present can flourish.