A Silent Crisis: The Stark Reality of Native American Healthcare Disparities

By [Your Name/Journalist Name]

In the vast, diverse tapestry of the United States, a profound paradox persists, often hidden in plain sight. For the nation’s First Peoples – Native Americans and Alaska Natives – access to adequate healthcare is not a given right, but a persistent struggle, marked by chronic underfunding, systemic neglect, and devastating health outcomes. The statistics tell a harrowing tale, painting a picture of disparities so stark they underscore a foundational broken promise, a modern-day crisis echoing centuries of injustice.

From the rolling plains of the Great Plains to the rugged peaks of the Southwest and the remote villages of Alaska, Indigenous communities face health challenges disproportionately higher than any other demographic group in the U.S. Their life expectancy is significantly lower, and they bear an overwhelming burden of preventable chronic diseases, mental health crises, and substance abuse. This isn’t merely a medical problem; it’s a societal one, deeply rooted in history, poverty, and a healthcare system struggling under the weight of chronic underinvestment.

A Legacy of Broken Promises: The Historical Context

To understand the current healthcare crisis, one must look back. The relationship between the U.S. government and Native American tribes is largely defined by treaties – agreements that often promised healthcare, education, and other services in exchange for vast tracts of ancestral lands. These promises, however, have been consistently underfunded or outright ignored.

The primary federal agency responsible for fulfilling these treaty obligations is the Indian Health Service (IHS), established in 1955. The IHS operates hospitals and clinics, and contracts with tribal organizations to provide care. Yet, it has been perpetually starved of resources. As one former IHS director famously stated, "IHS is not a health care system, it’s a payer of last resort." This chronic underfunding is the bedrock of many current disparities.

The Stark Numbers: A Picture of Disparity

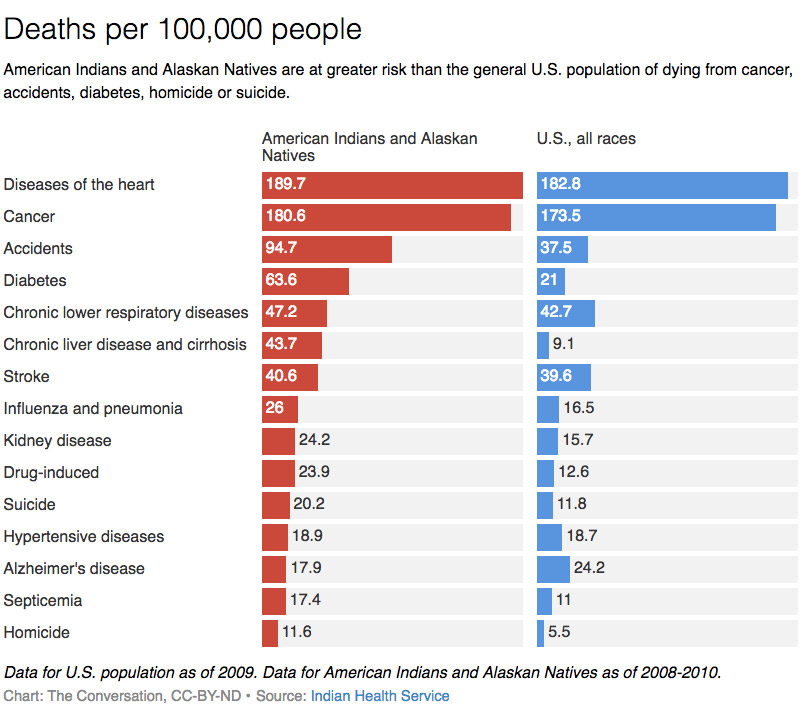

The numbers speak for themselves, revealing a systemic failure to provide equitable care:

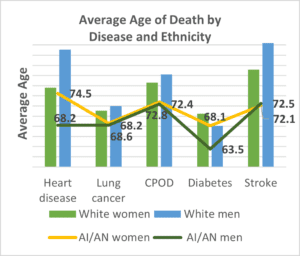

- Life Expectancy: Native Americans have a life expectancy that is 5.5 years lower than the U.S. all-races average. While the national average hovers around 78 years, for Native Americans, it’s closer to 72.

- Chronic Diseases:

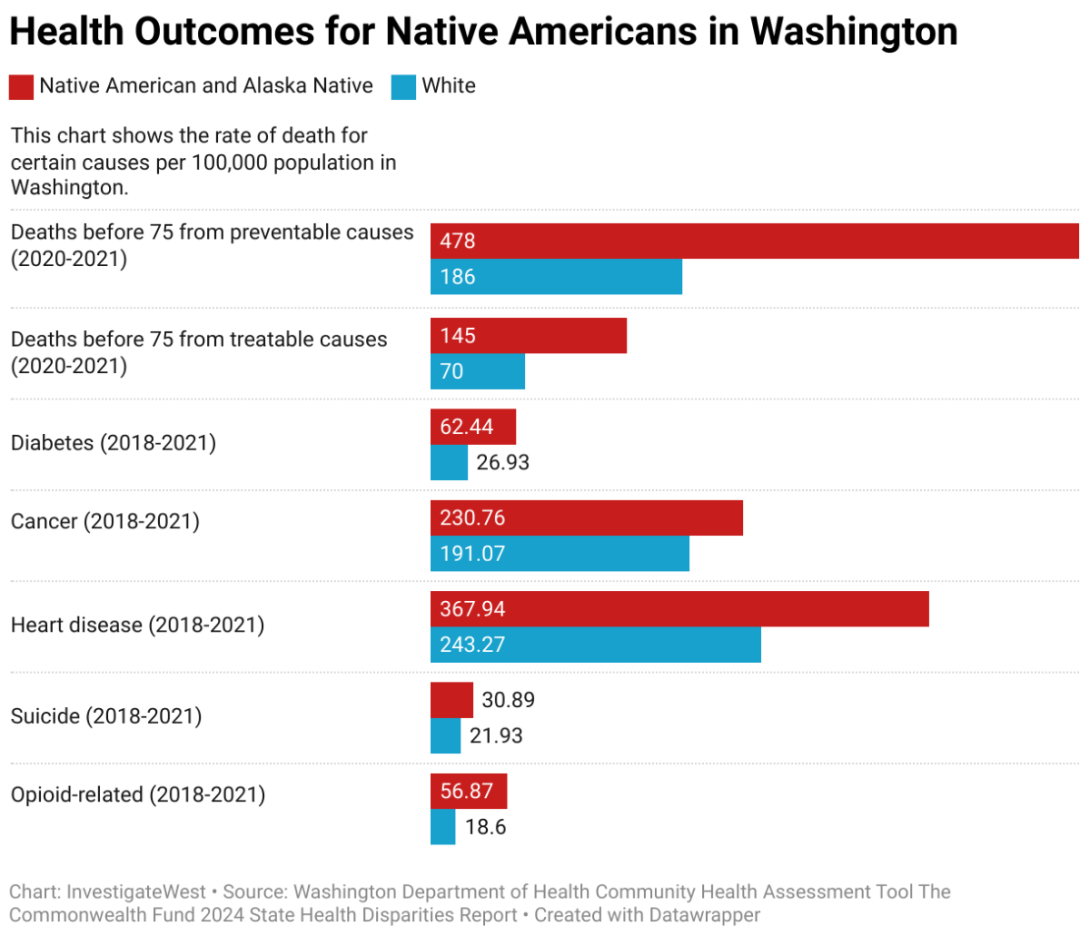

- Diabetes: Native Americans are 2 to 3 times more likely to be diagnosed with diabetes than non-Hispanic whites. For some tribes, the prevalence is even higher. This isn’t just a genetic predisposition; it’s linked to forced dietary changes, lack of access to healthy foods, and poverty.

- Heart Disease: Mortality rates from heart disease are significantly higher, particularly among younger Native American adults, often due to lack of early intervention and management.

- Tuberculosis: The incidence of tuberculosis among Native Americans is 600% higher than the national average.

- Chronic Liver Disease and Cirrhosis: Mortality rates from these conditions are 368% higher than the U.S. all-races average, largely driven by higher rates of alcohol abuse.

- Mental Health and Substance Abuse:

- Suicide: Suicide is the second leading cause of death for Native Americans aged 10-34, and the overall suicide rate for Native American youth is 1.5 times higher than the national average. This reflects the profound impact of historical trauma, discrimination, and lack of mental health resources.

- Substance Use Disorders: Rates of alcohol and drug abuse are elevated, often a coping mechanism for the deep-seated trauma and despair stemming from generations of systemic oppression, poverty, and cultural dislocation. Opioid overdose deaths have also seen a disturbing rise in many communities.

- Infant Mortality: The infant mortality rate for Native Americans is 20% higher than the national average, pointing to inadequate prenatal care, poor maternal health, and socioeconomic factors.

- Unintentional Injuries: Deaths due to unintentional injuries, including motor vehicle accidents and accidental poisonings (often drug-related), are 173% higher for Native Americans compared to all races.

The Underfunded Lifeline: The Indian Health Service

The most damning statistic regarding Native American healthcare often revolves around funding. The IHS is chronically and severely underfunded. Per capita, federal spending on healthcare for Native Americans through the IHS is a mere fraction of what is spent on other federal healthcare beneficiaries.

Consider this striking comparison: In recent years, the per capita spending for healthcare through the IHS has hovered around $4,078 per person. In stark contrast, federal spending on healthcare for federal prisoners is over $8,000 per person, for Medicare beneficiaries over $13,000, and for veterans over $14,000. This dramatic disparity illustrates a clear prioritization—or lack thereof—of the health of Native American communities.

This underfunding translates directly into limited access to care, long wait times for appointments, dilapidated facilities, a chronic shortage of healthcare providers (doctors, nurses, mental health professionals), and a severe lack of specialized services like cancer treatment or dialysis. Many tribal members must travel hundreds of miles, often across challenging terrain, to access even basic medical care.

Beyond the Clinic Walls: Social Determinants of Health

Healthcare disparities are not solely a product of clinic-level issues. They are deeply intertwined with the social determinants of health – the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age. For many Native American communities, these conditions are dire:

- Poverty: Native Americans experience the highest poverty rate of any racial group in the U.S. Poverty limits access to nutritious food, safe housing, and transportation to healthcare facilities.

- Food Insecurity: Many reservations are "food deserts," lacking grocery stores with fresh, healthy options, forcing reliance on processed, unhealthy foods that contribute to chronic diseases.

- Housing: Overcrowded and substandard housing contributes to the spread of infectious diseases like tuberculosis and respiratory illnesses.

- Education: Lower educational attainment can impact health literacy and employment opportunities, further exacerbating poverty.

- Infrastructure: Lack of clean water, proper sanitation, and reliable electricity in some remote communities directly impacts health and hygiene.

COVID-19: An Exacerbating Force

The COVID-19 pandemic laid bare and intensified these existing disparities. While some tribes implemented highly effective, proactive measures to protect their communities, Native Americans as a whole faced disproportionate risks. Data revealed that Native Americans were:

- 1.7 times more likely to be hospitalized with COVID-19 than white individuals.

- 2.1 times more likely to die from COVID-19 for certain age groups.

These higher rates were attributed to underlying health conditions (diabetes, heart disease), overcrowded housing, limited access to healthcare facilities, and the essential worker status of many tribal members. The pandemic served as a stark, immediate illustration of how decades of systemic neglect can turn a public health crisis into a catastrophe for vulnerable populations.

Resilience and the Path Forward: Sovereignty in Health

Despite these grim statistics, the narrative of Native American health is not one solely of despair. It is also a powerful story of resilience, self-determination, and a renewed commitment to tribal sovereignty. Many tribal nations are taking proactive steps to reclaim control over their health systems, integrating traditional healing practices with Western medicine, developing community-led health initiatives, and advocating fiercely for their rights.

Tribally-operated healthcare facilities, though often under-resourced, demonstrate incredible innovation and dedication. They are often more culturally competent, understanding the unique historical trauma and social contexts that impact their patients. They are working to address mental health with culturally appropriate counseling, tackle food insecurity with traditional food programs, and promote physical activity through community wellness initiatives.

The path forward requires a fundamental shift in approach:

- Consistent and Adequate Funding: The U.S. government must honor its treaty obligations by fully funding the IHS to parity with other federal healthcare systems. This means not just incremental increases, but a significant, sustained investment.

- Infrastructure Development: Investing in critical infrastructure on reservations – from clean water and sanitation to broadband internet – is essential for improving overall health.

- Culturally Competent Care: Training more Native American healthcare providers and integrating cultural competency into all aspects of care are vital for building trust and ensuring effective treatment.

- Addressing Social Determinants: Holistic approaches that tackle poverty, food insecurity, housing, and education are crucial for long-term health improvements.

- Tribal Self-Determination: Empowering tribes to design and manage their own healthcare systems, respecting their unique needs and traditions, is paramount.

The healthcare disparities faced by Native Americans are not merely statistics on a page; they represent a profound human cost, a daily struggle for millions of people who have been historically marginalized and underserved. Addressing this silent crisis is not just a matter of public health policy; it is a moral imperative, a step towards healing historical wounds, and an essential affirmation of justice for the First Peoples of this land. The time for promises without provision is over; the time for genuine investment and equity is now.