Echoes of the Wild: The Profound Legacy of Native American Traditional Hunting

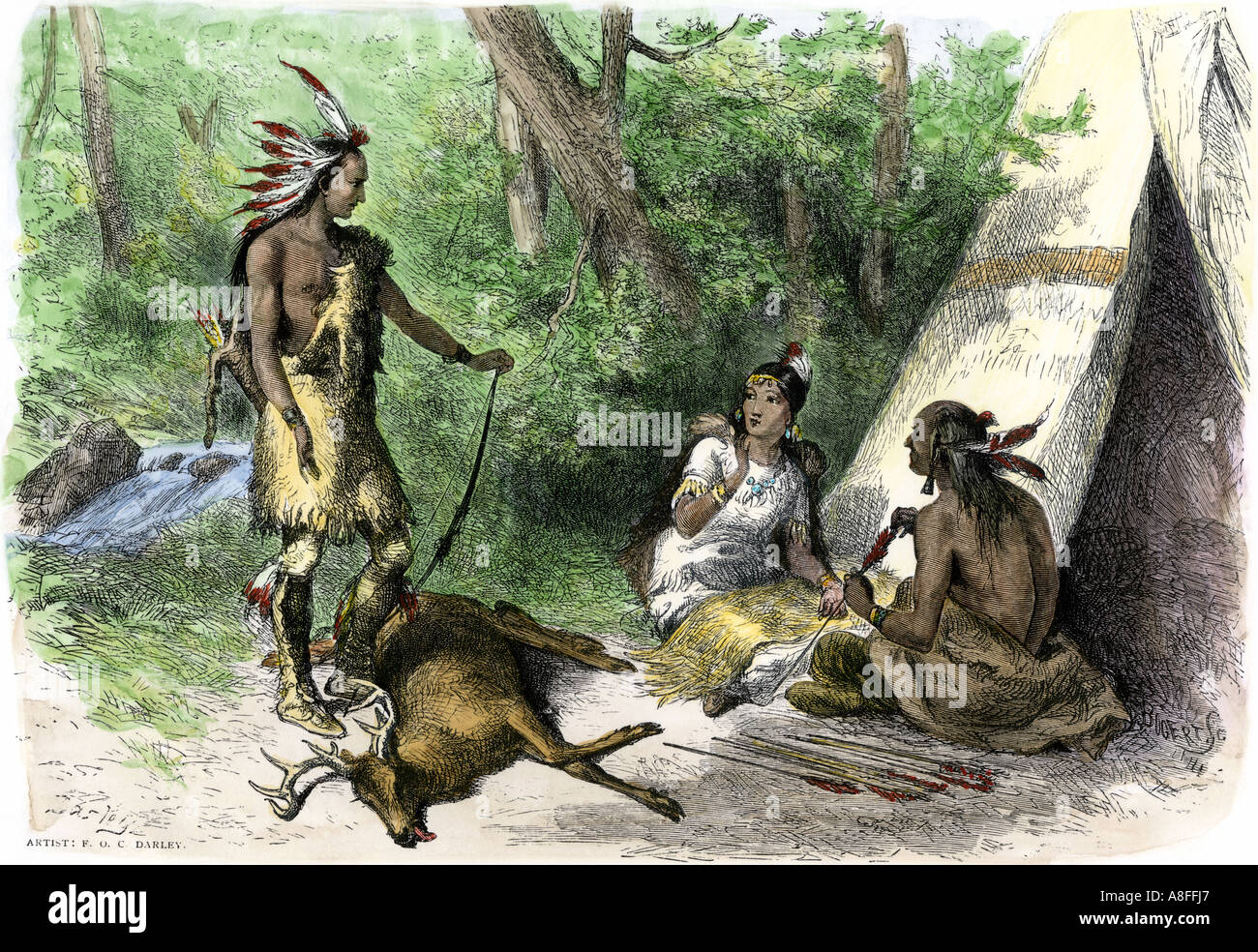

For millennia, long before the arrival of European settlers, the vast and varied landscapes of North America thrived with life. And intertwined with every ripple of river, every rustle of leaf, every thunder of hooves, were the Indigenous peoples whose very existence was predicated on an intimate, reciprocal relationship with the natural world. At the heart of this relationship lay traditional hunting practices – an intricate dance of survival, spirituality, and profound ecological wisdom that transcends the mere act of taking life for sustenance.

This was not simply about filling the belly; it was a way of life, a spiritual journey, a classroom for the young, and a testament to an unparalleled understanding of their environment. Native American hunting was a complex tapestry woven with threads of respect, sustainability, community, and an unshakeable belief in the interconnectedness of all living things.

A Philosophy of Reciprocity: More Than Just a Kill

To understand Native American hunting, one must first grasp the underlying philosophical framework. Unlike the European concept of dominion over nature, most Indigenous cultures viewed themselves as an integral part of the natural world, a thread in the great web of life. Animals were not simply resources; they were kin, teachers, and sacred beings.

"We do not inherit the earth from our ancestors; we borrow it from our children," is a sentiment often attributed to Native American wisdom, encapsulating their long-term perspective. This worldview fostered a deep sense of gratitude and reciprocity. A hunter would approach an animal with reverence, often offering prayers before and after a hunt, acknowledging the sacrifice the animal was making. The animal was seen as giving its life, not losing it, and this gift demanded respect and the responsible use of every part.

This spiritual connection manifested in various ways. Many tribes had specific ceremonies or rituals associated with hunting, designed to honor the animal’s spirit, ensure a successful hunt, and maintain balance with the natural world. For the Lakota, the Buffalo was more than just food; it was a sacred provider, embodying the generosity of the Great Spirit. Every part of the buffalo – meat, hide, bones, sinew, horns – was used, leaving virtually no waste. This practice wasn’t just practical; it was a deeply spiritual act of respect, ensuring that the animal’s sacrifice was not in vain.

Masters of the Land: Unparalleled Ecological Knowledge

The success of traditional Native American hunting rested on an astonishing depth of ecological knowledge. Hunters possessed an encyclopedic understanding of animal behavior, migration patterns, breeding cycles, preferred habitats, and even individual animal characteristics. They could read the land like a book – a broken twig, a disturbed stone, a faint scent on the wind – each clue telling a story of the creatures that moved through their territory.

Tracking was an art form passed down through generations. A skilled tracker could discern the species, age, sex, speed, and even the emotional state of an animal from its tracks. They understood the nuances of terrain, weather, and wind direction, using these elements to their advantage. For instance, knowing the prevailing winds was crucial for approaching prey undetected, as animals like deer and elk have an acute sense of smell.

Beyond individual animal knowledge, tribes also understood the broader ecosystem. They practiced what modern science now calls "conservation." They knew not to overhunt a specific species in a particular area, allowing populations to recover. They understood the concept of carrying capacity and the delicate balance of predator-prey relationships. Some tribes even used controlled burns to manage forests and grasslands, promoting new growth that attracted game animals and enhanced biodiversity. This was not a reactive conservation; it was an inherent, proactive stewardship, ensuring the health of the land for future generations.

Ingenious Tools and Techniques: A Testament to Human Ingenuity

Traditional Native American hunting tools, though often described as "primitive," were incredibly sophisticated and perfectly adapted to their environment.

The bow and arrow was perhaps the most iconic and widely used hunting tool. Made from materials like osage orange, hickory, or juniper wood, often reinforced with sinew for added power, these bows were marvels of engineering. Arrows, tipped with meticulously crafted flint, obsidian, or bone points, were designed for maximum penetration. The efficiency of the bow and arrow allowed for selective hunting, targeting specific animals without disturbing the wider herd.

Before the widespread adoption of the bow, the atlatl, or spear-thrower, was a primary hunting weapon for thousands of years. This simple yet effective device, essentially a lever that extended the arm, allowed a hunter to hurl a spear with much greater force and speed than by hand alone. Archaeological evidence suggests its use in hunting megafauna like mammoths and mastodons during the Paleo-Indian period.

Beyond individual weapons, Native Americans employed a variety of ingenious techniques:

- Communal Hunts: For large game like bison, communal hunts were common. The buffalo jump (like the famous Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump in Alberta, Canada) was a highly organized and dangerous technique where entire herds were stampeded over cliffs, providing vast amounts of food and resources for an entire community. This required immense planning, coordination, and an intimate understanding of bison behavior.

- Traps and Snares: Smaller game, birds, and fish were often caught using cleverly designed traps, snares made from plant fibers, and nets woven from natural materials.

- Disguise and Decoys: Hunters would often wear disguises, such as deer or wolf hides, to get closer to their prey. Decoys, crafted from wood or animal parts, were also used to lure animals within range.

- Fish Weirs: In areas rich with aquatic life, elaborate fish weirs – structures built across rivers or streams to funnel fish into traps – demonstrated advanced engineering and an understanding of hydrology.

The Fabric of Community: Sharing the Bounty

Hunting was rarely a solitary endeavor, and its success directly contributed to the social cohesion of the tribe. A successful hunt, especially of large game, meant food for everyone. The meat was distributed according to established social protocols, often with the most vulnerable members of the community – the elderly, the sick, and young children – receiving priority. This ensured that no one went hungry and reinforced bonds of reciprocity and mutual support.

Hunting expeditions were also significant rites of passage for young men, teaching them not only practical skills but also patience, discipline, spiritual reverence, and their responsibilities to the community. Elders would impart generations of knowledge, stories, and the sacred songs associated with the hunt, linking the present to the past and ensuring the continuity of cultural identity.

The Great Disruption: Impact of Colonization

The arrival of European settlers marked a catastrophic turning point for Native American traditional hunting practices. The introduction of firearms, while initially adopted by some tribes, fundamentally altered the balance. More devastating, however, was the systematic destruction of Indigenous lands and the deliberate annihilation of key game species, most notably the American bison.

The buffalo, which once numbered in the tens of millions, was central to the survival and spiritual life of many Plains tribes. Its decimation, driven by market demand for hides and, more sinisterly, as a military strategy to subjugate Native Americans by destroying their food source, led to widespread starvation and cultural collapse. From the 1830s to the 1880s, millions of bison were slaughtered, reducing the herds to a few hundred by the turn of the century. This act was not just an ecological disaster; it was an act of cultural genocide, severing the deep spiritual and economic ties Indigenous peoples had with their primary provider.

Furthermore, the imposition of reservation systems, the criminalization of traditional practices, and the forced assimilation policies aimed to strip Native Americans of their cultural identity, including their hunting traditions. Access to traditional hunting grounds was denied, and tribal sovereignty over their resources was undermined.

Resilience and Revival: Reclaiming a Sacred Heritage

Despite centuries of oppression and disruption, Native American traditional hunting practices have shown remarkable resilience. Today, many tribes are actively engaged in cultural revitalization efforts, including the reclamation of their hunting heritage. This involves:

- Restoring Land and Wildlife: Tribes are at the forefront of conservation efforts, working to restore traditional lands and reintroduce native species, including bison.

- Reclaiming Sovereignty: Legal battles continue to secure and uphold treaty rights that guarantee hunting and fishing rights on traditional territories. The landmark U.S. v. Washington (Boldt Decision) in 1974, for instance, affirmed tribal fishing rights, highlighting the ongoing struggle for recognition.

- Intergenerational Knowledge Transfer: Elders are actively teaching younger generations the ancient skills, spiritual protocols, and ecological wisdom associated with traditional hunting. Programs focused on teaching tracking, hide tanning, bow making, and traditional food preparation are vital to this revival.

- Adapting to Modern Challenges: While modern tools may be used, the underlying philosophy of respect, sustainability, and gratitude remains paramount. Challenges include navigating complex state and federal hunting regulations, gaining access to fragmented traditional lands, and countering stereotypes about Native American hunting.

The story of Native American traditional hunting is far more than a historical footnote; it is a living testament to humanity’s profound potential for coexistence with the natural world. It offers invaluable lessons for contemporary society struggling with environmental degradation, unsustainable consumption, and a disconnect from the sources of our sustenance. By understanding and respecting these ancient practices, we gain not only a deeper appreciation for Indigenous cultures but also a vital roadmap for a more sustainable, respectful, and interconnected future. The echoes of the wild, carried through generations, continue to speak of a wisdom we desperately need to hear.