Alaska’s Enduring Heartbeat: The Resilience of Its Native Peoples

Alaska, the Last Frontier, conjures images of majestic mountains, vast wilderness, and a rugged, untamed spirit. Yet, beneath this iconic landscape lies a profound human story, thousands of years in the making: that of Alaska’s Native peoples. Far from a monolithic entity, the Indigenous communities of Alaska represent an astonishing tapestry of cultures, languages, and traditions, each uniquely shaped by their ancestral lands and waters.

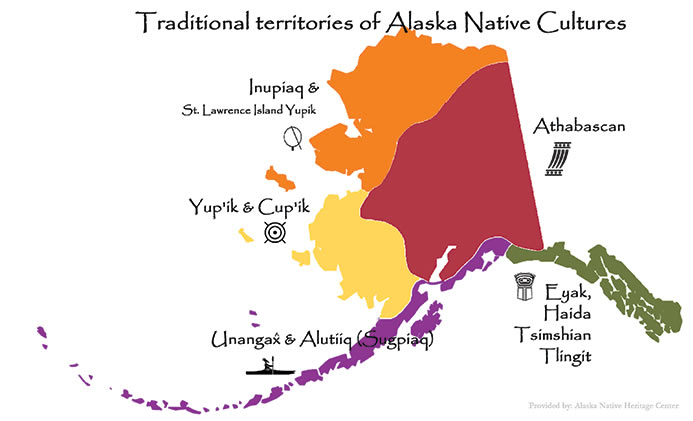

Often broadly referred to as "Native Americans," the preferred and more accurate term for the Indigenous inhabitants of Alaska is "Alaska Natives." This distinction is crucial, reflecting their unique history, land claims, and cultural identities, which differ significantly from those of Native American tribes in the Lower 48 states. From the icy shores of the Arctic to the temperate rainforests of the Southeast and the windswept Aleutian Islands, Alaska Native cultures are as diverse as the immense state itself, encompassing eleven major cultural groups and over 20 distinct languages.

A Tapestry of Cultures: Adapting to Extremes

The sheer geographic scale of Alaska has fostered incredible cultural diversity. In the Arctic and Subarctic regions, the Inupiaq and Yup’ik peoples, often grouped under the broader term Inuit, have mastered survival in some of the planet’s harshest environments. Their lives traditionally revolved around marine mammals – whales, seals, and walrus – hunted from open boats (umiaq) or through ice holes. Their intricate knowledge of sea ice, animal behavior, and the changing seasons is unparalleled, reflected in their rich oral traditions, dance, and spiritual practices. The Yup’ik, in particular, are renowned for their vibrant mask-making traditions, used in ceremonial dances to connect with the spirit world.

Moving inland, across the vast interior, reside the Athabascan peoples, including groups like the Gwich’in, Koyukon, Tanana, and Ahtna. Their cultures are centered around the great rivers and forests, relying on caribou, moose, fish (especially salmon), and trapping. They are known for their intricate beadwork, hide tanning, and a profound respect for the land as their provider. Their semi-nomadic lifestyle, dictated by the movements of game, contrasts sharply with the coastal communities.

Along the rugged southern coast and islands, including Kodiak and Prince William Sound, live the Alutiiq (Sugpiaq) and Unangax̂ (Aleut). These maritime peoples were master kayakers (qayaq builders) and highly skilled hunters of sea otters, seals, and fish, navigating the treacherous waters of the North Pacific. Their history is deeply intertwined with the earliest European contacts, particularly the Russian fur trade, which brought both new technologies and devastating disease.

In the lush, temperate rainforests of Southeast Alaska, the Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian peoples thrive. These groups are famous for their magnificent cedar longhouses, intricate totem poles that narrate family histories and legends, elaborate weaving (Chilkat blankets), and powerful ceremonial potlatches. Their societies are highly stratified, with complex clan systems and a deep reverence for the salmon, which forms the cornerstone of their traditional diet and economy.

A History Forged in Change and Resilience

For millennia, these cultures flourished, guided by traditional ecological knowledge passed down through generations. The arrival of Europeans, however, irrevocably altered their world. Russian fur traders, beginning in the mid-18th century, exploited the rich fur resources, particularly the sea otter, and often brutalized Native populations, especially the Unangax̂. Orthodox Christianity, introduced by Russian missionaries, was also widely adopted, and remains a significant cultural force in many communities today.

The purchase of Alaska by the United States from Russia in 1867 ushered in a new era of Americanization. This period saw the establishment of boarding schools, often run by religious institutions, where Alaska Native children were forcibly removed from their families, forbidden to speak their languages, and punished for practicing their cultural traditions. This traumatic experience, intended to "kill the Indian to save the man," resulted in profound intergenerational trauma, language loss, and the erosion of cultural identity that communities are still working to heal from today.

The 20th century brought further transformations. The discovery of oil in Prudhoe Bay in the late 1960s became a pivotal moment. The proposed Trans-Alaska Pipeline route crossed vast Native lands, leading to the urgent need to settle aboriginal land claims. This culminated in the landmark Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) of 1971.

ANCSA was revolutionary, extinguishing aboriginal claims to most of Alaska in exchange for 44 million acres of land and nearly $1 billion. Critically, it did not create reservations (as in the Lower 48) but instead established 13 regional Alaska Native corporations and over 200 village corporations. These corporations were granted the land and capital, tasked with managing resources and generating economic benefits for their Alaska Native shareholders.

ANCSA: A Double-Edged Legacy

ANCSA’s impact is complex and often debated. On one hand, it provided Alaska Natives with an unprecedented land base and significant economic power, enabling self-determination and investment in their communities. Many corporations have become major economic players in Alaska, providing jobs, scholarships, and services to their shareholders.

However, ANCSA also imposed a Western corporate model onto Indigenous societies, often leading to internal divisions between shareholders and traditional tribal governments. It blurred the lines between cultural identity and economic enterprise, and the corporate structure sometimes struggled to reconcile profit motives with traditional values of communal land use and subsistence. Unlike federally recognized tribes in the Lower 48, Alaska Native tribes were left without a formal "reservation" land base, complicating issues of sovereignty and jurisdiction. "ANCSA was a monumental compromise," notes Willie Hensley, an Inupiaq elder and key architect of the Act. "We gained control of our land and a place at the table, but we also had to adapt to a very different way of doing business."

Contemporary Challenges: Climate, Health, and Identity

Today, Alaska Native communities face a confluence of pressing challenges. Perhaps the most existential threat is climate change. Alaska is warming at twice the rate of the rest of the world, leading to rapidly thawing permafrost, coastal erosion, and unpredictable ice conditions. Villages built on permafrost are sinking, and coastal communities are literally washing into the sea, forcing difficult and costly decisions about relocation. "Our ice is changing, our hunting grounds are moving, and our homes are disappearing," says Esau Sinnok, an Inupiaq climate advocate from Shishmaref, a village on the brink of being lost to erosion. "This isn’t just about environmental policy; it’s about our way of life, our identity, and our very existence."

Beyond environmental shifts, Alaska Native communities grapple with significant social and health disparities. Historical trauma from colonization, boarding schools, and cultural suppression contributes to higher rates of suicide, substance abuse, and chronic health conditions. Access to quality healthcare, education, and economic opportunities remains a challenge in many remote villages.

Language loss is another critical concern. Of the over 20 distinct Alaska Native languages once spoken, many are now critically endangered, with only a handful of fluent elders remaining. The loss of language is not merely the loss of words; it’s the erosion of unique ways of understanding the world, traditional knowledge, and cultural identity.

Resilience and Revitalization: Forging a Future

Despite these formidable challenges, the story of Alaska Natives is one of remarkable resilience and vibrant revitalization. There is a powerful resurgence of cultural pride and self-determination across the state.

Language immersion programs, often spearheaded by community members and elders, are working tirelessly to teach younger generations their ancestral tongues. Traditional arts, such as weaving, carving, and storytelling, are experiencing a renaissance, celebrated in cultural centers and museums. Ceremonial practices and traditional dances are being revived, strengthening community bonds and connecting youth to their heritage.

Tribal governments, separate from the ANCSA corporations, are asserting their inherent sovereignty, working to address social issues, protect subsistence rights, and advocate for their communities at state and federal levels. They are building partnerships, developing sustainable economies, and embracing modern technologies while holding fast to ancient wisdom.

Alaska Natives are also at the forefront of advocating for climate justice, sharing their Traditional Ecological Knowledge with the scientific community and global leaders. Their deep understanding of the Arctic environment offers invaluable insights into adapting to and mitigating climate change.

In conclusion, the Alaska Native peoples are not a relic of the past but a vibrant, living presence, deeply woven into the fabric of Alaska. Their journey—marked by profound connection to the land, historical trauma, and innovative adaptation—speaks to the enduring power of culture and the indomitable human spirit. As Alaska navigates the complexities of the 21st century, the voices, wisdom, and resilience of its Native peoples will undoubtedly continue to shape its future, ensuring that the heartbeat of Alaska continues to resonate with the echoes of its first inhabitants.