Echoes in the Ozarks: The Enduring Spirit of Native American Tribes in Arkansas

Arkansas, often dubbed "The Natural State," is celebrated for its rugged mountains, fertile delta lands, and winding rivers. But beneath the surface of its picturesque landscapes and modern development lies a rich, complex, and often painful history – one deeply intertwined with the Native American tribes who called this land home for millennia. Long before European settlers carved out farms and towns, sophisticated indigenous societies thrived here, leaving behind a legacy that, while sometimes obscured, continues to resonate in the very fabric of the state.

This is not merely a tale of the past; it is a story of resilience, forced removal, and the enduring spirit of nations whose ancestral ties to Arkansas remain potent, even if their physical presence was brutally curtailed. From ancient mound builders to the sovereign nations fighting for self-determination today, the narrative of Native Americans in Arkansas is a crucial chapter in the larger American story.

A Land of Ancient Civilizations: The First Arkansans

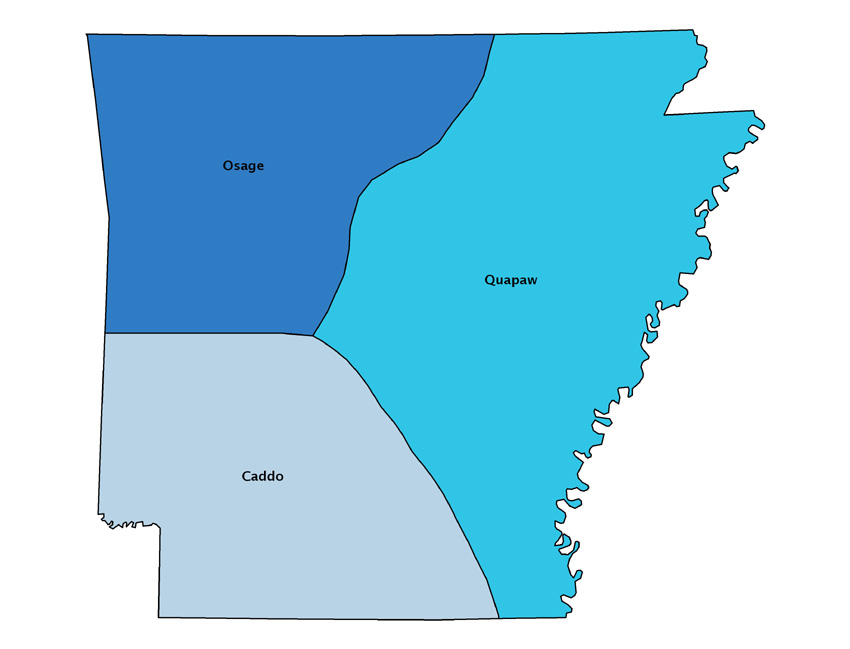

For over 12,000 years, diverse indigenous peoples inhabited what is now Arkansas. Their societies were complex, their cultures vibrant, and their connection to the land profound. Among the most prominent were the Quapaw, the Caddo, and the Osage.

The Quapaw, or "Akansea" as they were known by the Algonquian-speaking tribes further north (a name that eventually evolved into "Arkansas"), lived primarily in the rich delta lands along the Arkansas River. They were skilled farmers, cultivating corn, beans, and squash, and adept hunters and fishers. Their villages were well-organized, their social structures intricate, and their pottery renowned for its beauty and craftsmanship. They maintained complex trade networks and alliances with neighboring tribes.

To the south and west, along the Red River and its tributaries, lived the Caddo. Their confederacies spanned across what is now southwestern Arkansas, Louisiana, Texas, and Oklahoma. The Caddo were also accomplished agriculturalists, known for their distinctive conical grass houses and sophisticated pottery. They were expert traders, controlling vital trade routes and acting as intermediaries between tribes of the Plains and the Southeast. Their spiritual beliefs were deeply connected to the earth, and their ceremonies honored the cycles of nature.

Further north, in the Ozark and Ouachita Mountains and extending into the plains of Missouri and Kansas, were the formidable Osage. These powerful hunters and warriors controlled vast territories, renowned for their strategic prowess and their mastery of the buffalo hunt. Their semi-nomadic lifestyle allowed them to exploit different ecosystems, living in permanent villages during planting and harvest seasons, and then moving onto the plains for their seasonal hunts. The Osage were characterized by a strong sense of identity, a disciplined social order, and a deep spiritual connection to the "Great Mystery."

Beyond these major groups, the state also saw the presence of other tribes, including elements of the Tunica, Koroa, and others, often interacting, trading, and sometimes warring with their neighbors. A powerful testament to these sophisticated societies is Toltec Mounds State Park near Scott, Arkansas. While not built by the Toltec people of Mesoamerica, the name refers to the grand scale of the site. From about 650 to 1050 CE, this was a major ceremonial and political center of the Plum Bayou culture, a Mississippian-era society. The impressive earthen mounds, including a large platform mound and a ceremonial plaza, stand as silent sentinels, reminding us of the advanced astronomical knowledge and communal organization of these early inhabitants. As Dr. George Sabo III, an archaeologist at the University of Arkansas, noted, "The Toltec Mounds site represents a monumental achievement of early Arkansas peoples, demonstrating their complex social structures and deep understanding of their environment."

The Shadow of Contact: Disease, Diplomacy, and Dispossession

The arrival of Europeans in the 16th century marked a profound turning point. Hernando de Soto’s brutal expedition in the 1540s brought not only violence but also devastating diseases like smallpox, to which Native Americans had no immunity. Entire villages were decimated, disrupting social structures and weakening tribal populations long before permanent European settlements were established.

The French were the first to establish a lasting presence, founding Arkansas Post in 1686. This remote trading outpost became a nexus of interaction, commerce, and diplomacy between the French and the Quapaw. For a time, the relationship was largely one of mutual benefit, with the Quapaw serving as crucial allies and trading partners for the French. They exchanged furs, food, and knowledge for European goods like tools, firearms, and textiles. However, even these seemingly beneficial relationships introduced new dependencies and vulnerabilities, as tribal economies became integrated into the global fur trade.

As European powers – first France, then Spain, then the United States – vied for control of the continent, Native American tribes found themselves caught in a geopolitical struggle. Promises made in treaties were systematically broken, and the concept of land ownership, foreign to most indigenous cultures, became a tool of dispossession.

The Era of Removal: A Trail of Tears and Broken Promises

The 19th century brought an era of unparalleled displacement. With the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the United States acquired vast new territories, including Arkansas, and with them, the "Indian Problem." The prevailing sentiment, fueled by westward expansion and racial prejudice, was that Native Americans were obstacles to progress and should be removed from their ancestral lands.

The Indian Removal Act of 1830, championed by President Andrew Jackson, formalized this policy. While often associated with the Cherokee Nation’s infamous "Trail of Tears," the act impacted numerous tribes across the Southeast, including those in Arkansas.

The Quapaw, despite their long history of cooperation with the French and Americans, were among the first to face forced removal. Through a series of treaties in the 1820s, they were compelled to cede nearly all of their traditional lands in Arkansas. Many were forcibly relocated to a small reservation in Louisiana, suffering immense hardships, disease, and starvation. "The forced removal was a catastrophic event for our people," says a representative voice from the Quapaw Nation. "Our ancestors endured unimaginable suffering, but their spirit of survival laid the foundation for us today." Many later returned to a new reservation in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma), a fraction of their original domain.

The Osage, too, faced immense pressure. Having ceded large tracts of land in Missouri, Kansas, and northern Arkansas through a series of treaties, they were eventually confined to a reservation in Indian Territory. Their vast hunting grounds in the Ozarks and beyond were lost forever.

While the Caddo had already been pushed west into Texas, their connection to Arkansas was severed. The infamous "Trail of Tears" of the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole nations also passed through Arkansas, as tens of thousands of people were forcibly marched across the state, leaving a devastating trail of sickness, death, and profound sorrow. The memory of these forced marches is etched into the landscape and the collective consciousness of these nations.

The Enduring Connection: From Removal to Revival

Yet, the story does not end with forced removal. The vibrant cultures and identities of these tribes were not extinguished. Though their ancestral lands in Arkansas were taken, their connection to them remains. Today, the descendants of the Quapaw, Caddo, and Osage, among others, live predominantly in Oklahoma, where their tribal governments are sovereign nations, actively working to preserve their heritage and build a future for their people.

The Quapaw Nation, headquartered in Quapaw, Oklahoma, is a powerful example of resilience and economic self-sufficiency. Leveraging their sovereignty, they have diversified their economy, notably through the development of successful enterprises like the Downstream Casino Resort, which generates revenue for tribal services, education, and cultural programs. They maintain a strong cultural identity, working to revive their language (Osage-Quapaw), preserve their traditional ceremonies, and educate their youth about their rich history, including their deep ties to Arkansas. "Our roots are in Arkansas," states a Quapaw Nation elder, "and though we were forced away, that connection is forever in our blood and in our stories. We remember our ancestors and we honor their sacrifices by continuing to thrive."

The Osage Nation, now based in Pawhuska, Oklahoma, also continues to thrive, having famously benefited from oil discovered on their reservation lands. They have invested heavily in cultural preservation, language immersion programs, and educational initiatives, ensuring that the Osage way of life endures for future generations. Similarly, the Caddo Nation of Oklahoma, while smaller in number, is dedicated to revitalizing its language, preserving its ancestral knowledge, and celebrating its unique cultural identity, acknowledging its historical presence in Arkansas.

Remembering and Reclaiming the Narrative

For many Arkansans, the Native American presence in the state’s history is often overlooked or relegated to a distant past. However, efforts are underway to reclaim and highlight this crucial narrative. Historical markers, museum exhibits, and educational programs are slowly beginning to shed light on the vibrant pre-Columbian societies and the devastating impact of removal.

Understanding this history is not just about acknowledging past injustices; it’s about recognizing the enduring strength and contributions of Native American peoples. It’s about seeing the landscape not just as "natural," but as deeply imbued with thousands of years of human habitation, spiritual significance, and cultural legacy.

As the sun sets over the Arkansas River, it casts long shadows over lands that once belonged to the Quapaw. The wind whispers through the ancient trees of the Ozarks, carrying echoes of Osage hunters. And the fertile soil of the delta holds the memories of Caddo farmers. The Native American story in Arkansas is one of profound loss, but also of incredible survival and unwavering spirit. It is a story that demands to be heard, understood, and respected, ensuring that the echoes of the past guide us toward a more inclusive and just future.