Beyond ‘Native American’: Exploring the Diverse World of Canada’s Indigenous Peoples

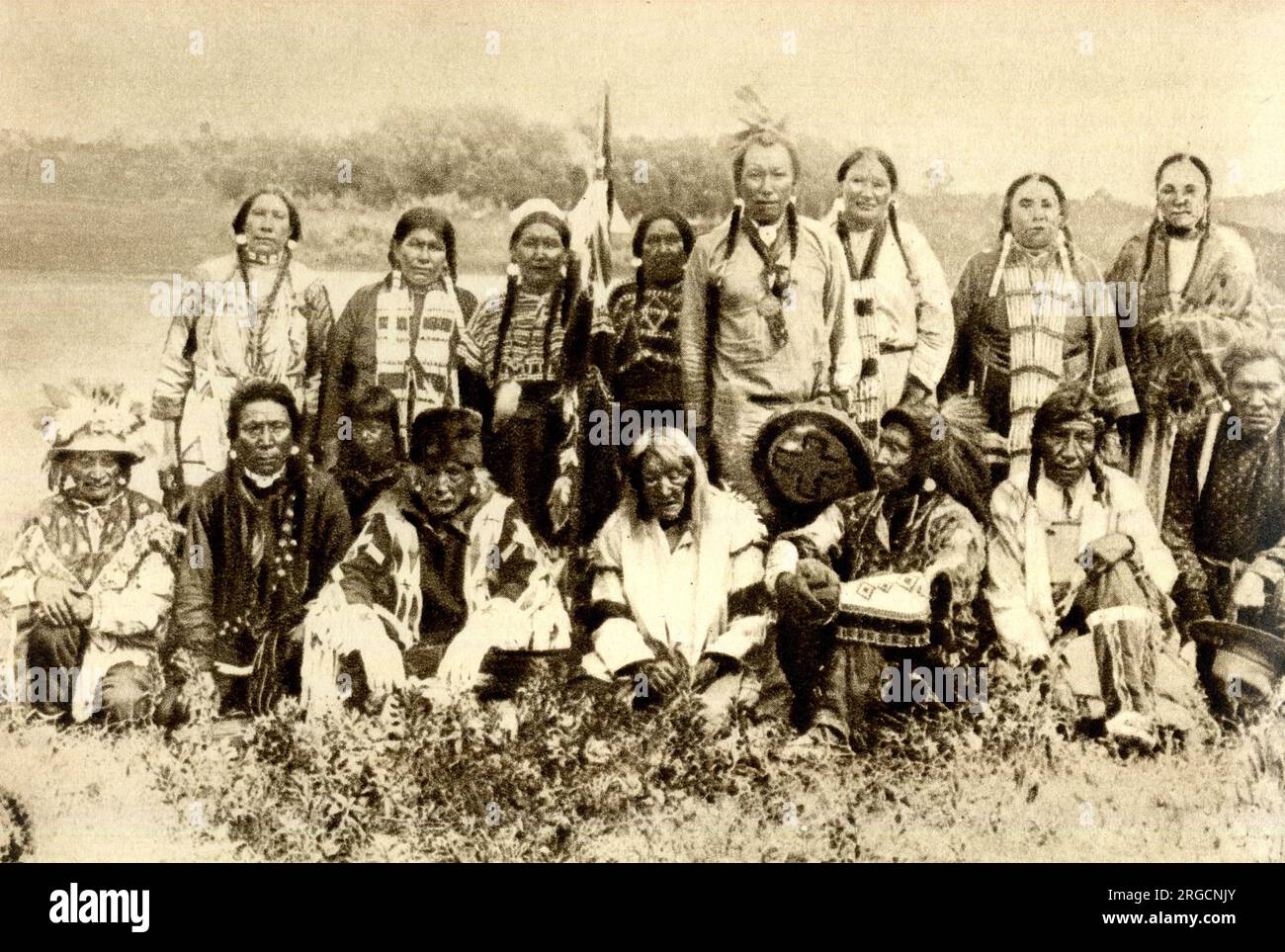

When one speaks of "Native American tribes," images of the vast plains or desert Southwest of the United States often come to mind – the Sioux, the Navajo, the Apache. However, across the northern border, in Canada, the landscape of Indigenous identity is distinct, deeply rich, and far more nuanced than the general term "Native American" can convey. While sharing a common thread of pre-colonial inhabitation and subsequent colonial experience with their counterparts to the south, the Indigenous peoples of Canada prefer to be identified by terms that reflect their unique histories, cultures, and legal relationships with the Canadian state: First Nations, Inuit, and Métis.

This distinction is not merely semantic; it speaks to the very heart of identity, sovereignty, and the ongoing journey toward reconciliation. To understand the vibrant and complex tapestry of Canada’s Indigenous communities is to embark on a journey through millennia of history, profound cultural diversity, systemic injustices, and remarkable resilience.

The Name Game: Deciphering Terminology

The primary reason "Native American" is generally avoided in Canada is due to self-identification and the historical and legal context of the country.

-

First Nations: This is the most common term used to describe the diverse Aboriginal peoples in Canada who are not Inuit or Métis. There are over 630 distinct First Nations communities across Canada, speaking more than 50 different Indigenous languages. Each First Nation has its own unique history, culture, governance, and traditional territories. Examples include the Haida of the Pacific Northwest, the Cree of the Prairies and Subarctic, the Anishinaabe (Ojibwe) of the Great Lakes region, and the Mohawk of the Iroquois Confederacy in the East. The term "First Nations" collectively recognizes these distinct nations as the original peoples of the land, asserting their inherent rights and sovereignty.

-

Inuit: The Inuit are the Indigenous people of the Arctic regions of Canada, Alaska, Greenland, and Siberia. In Canada, their traditional territory, known as Inuit Nunangat, encompasses vast areas of the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, northern Quebec (Nunavik), and Labrador (Nunatsiavut). Culturally and linguistically distinct from First Nations, the Inuit have adapted to the harsh Arctic environment for thousands of years, developing unique traditions, hunting practices, and an intricate knowledge of their land. The creation of Nunavut in 1999, a vast territory governed primarily by Inuit, stands as a landmark achievement in self-determination.

-

Métis: The Métis are a distinct Indigenous people whose origins lie in the intermarriage of European fur traders (primarily French and Scottish) and First Nations women (often Cree, Ojibwe, or Saulteaux) in the 18th and 19th centuries, primarily in the Red River Valley of what is now Manitoba. They developed a unique culture, language (Michif), and a strong sense of nationhood, playing a pivotal role in the development of Western Canada. The Métis Nation has a distinct history of self-governance and resistance, notably led by Louis Riel, and continues to advocate for their rights and recognition as a distinct Indigenous people.

These three groups – First Nations, Inuit, and Métis – are collectively referred to as "Indigenous Peoples" or "Aboriginal Peoples" in Canada. The choice of terminology reflects a deep respect for self-determination and cultural specificity, a critical aspect of reconciliation.

A Tapestry of Nations: Diversity and Traditional Territories

The sheer diversity of First Nations in Canada is staggering. From the ancient cedar longhouses of the Kwakwaka’wakw on the Pacific coast, whose intricate art and potlatch ceremonies are renowned, to the nomadic hunting traditions of the Dene in the Subarctic, or the agricultural prowess and political sophistication of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) in the East, each nation possesses a unique worldview, language, and system of governance.

The concept of "traditional territories" is paramount. Long before the arrival of Europeans, Indigenous nations lived according to their own laws, customs, and spiritual beliefs, managing their lands and resources sustainably. These territories often spanned vast areas, connecting communities through intricate trade networks and alliances. The imposition of colonial boundaries and the creation of "reserves" (parcels of land set aside for First Nations, often small and remote) drastically altered these traditional relationships with the land, leading to significant social and economic challenges that persist today.

A Shadowed Past: Colonialism and Its Enduring Legacy

The arrival of European explorers and settlers in what is now Canada irrevocably changed the course of Indigenous history. Initially, relationships were often based on trade and mutual assistance, particularly during the fur trade era. However, as European settlement intensified, the balance of power shifted dramatically.

The Canadian government, through a series of policies and legislation, systematically sought to assert control over Indigenous lands, resources, and lives. The most impactful of these was the Indian Act of 1876, which remains in force today, albeit with numerous amendments. This highly paternalistic and assimilationist legislation defined who was "Indian," dictated how First Nations could govern themselves, controlled their land and resources, and suppressed their cultural practices. It created the "reserve system" and imposed a band council system that often undermined traditional governance structures.

However, no single policy inflicted more profound and lasting trauma than the residential school system. For over a century, from the 1870s until the last school closed in 1996, more than 150,000 Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their families and communities and placed in church-run, government-funded residential schools. The stated goal was to "kill the Indian in the child" – to strip children of their Indigenous languages, cultures, and spiritual beliefs and assimilate them into dominant Canadian society.

The reality was horrific. Children suffered widespread physical, emotional, and sexual abuse. They were denied contact with their families, forbidden to speak their languages, and taught to be ashamed of their heritage. The intergenerational trauma resulting from these schools continues to impact Indigenous families and communities today, contributing to disproportionately high rates of poverty, substance abuse, mental health issues, and incarceration.

As Justice Murray Sinclair, former chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC), famously stated: "We have described for you a cultural genocide. We have described for you how the institutions of the country were used to destroy a culture and a way of life."

Beyond residential schools, other policies like the Sixties Scoop, where Indigenous children were taken from their families by child welfare services and adopted into non-Indigenous homes, and the ongoing crisis of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG), further underscore the systemic discrimination and violence faced by Indigenous peoples in Canada.

The Path to Reconciliation and Self-Determination

Despite the immense challenges and historical injustices, Indigenous peoples in Canada have demonstrated extraordinary resilience and a tenacious commitment to revitalizing their cultures, languages, and political autonomy.

The late 20th and early 21st centuries have seen significant strides in Indigenous rights and reconciliation efforts. Key milestones include:

- The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP, 1996): This comprehensive report documented the historical injustices and made wide-ranging recommendations for addressing them, laying much of the groundwork for future policy.

- The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC, 2008-2015): Established to document the impacts of the residential school system, the TRC released 94 Calls to Action, urging all levels of government and Canadian society to embark on a journey of reconciliation. These calls cover areas from child welfare and education to justice and health, and are a roadmap for systemic change.

- The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP): Adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2007, UNDRIP affirms the collective and individual rights of Indigenous peoples. Canada initially voted against it but fully endorsed it in 2016 and passed legislation in 2021 to implement it. This means Canadian laws must be consistent with the Declaration.

- Modern Treaties and Self-Governance Agreements: Beyond historical treaties, modern treaties (often called Comprehensive Land Claims Agreements) and self-governance agreements have been negotiated across the country. These agreements recognize Indigenous title, rights, and jurisdiction over land and resources, and establish frameworks for Indigenous self-government. A prime example is the Nisga’a Final Agreement in British Columbia, which came into effect in 2000, granting the Nisga’a Nation control over their land, resources, and governance.

- Cultural Revitalization: There is a powerful resurgence of Indigenous languages, traditional art forms, ceremonies, and knowledge systems. Communities are establishing language immersion programs, revitalizing traditional governance models, and celebrating their heritage with renewed pride. The global popularity of Indigenous artists, musicians, and storytellers from Canada is a testament to this vibrant cultural revival.

Enduring Challenges and Future Prospects

While significant progress has been made, the journey towards true reconciliation is far from over. Indigenous peoples in Canada continue to face disproportionate challenges, including:

- Socioeconomic Disparities: Higher rates of poverty, lower educational attainment, poorer health outcomes, and inadequate housing persist in many Indigenous communities, particularly on reserves.

- Systemic Racism: Indigenous peoples frequently encounter racism and discrimination within the healthcare, justice, and education systems.

- Resource Development Conflicts: Tensions often arise between Indigenous land rights and resource extraction projects (e.g., pipelines, mining), highlighting the ongoing need for meaningful consultation and consent.

- Access to Justice: Overrepresentation of Indigenous peoples in the criminal justice system remains a critical issue, driven by systemic factors and historical injustices.

Yet, the narrative is not solely one of hardship. Indigenous communities are also at the forefront of innovation and leadership. From establishing successful Indigenous-led businesses and economic development corporations that provide jobs and prosperity, to advocating for environmental protection and sustainable practices, Indigenous peoples are actively shaping Canada’s future. The increasing number of Indigenous leaders, artists, academics, and politicians is a powerful indicator of this growing influence and self-determination.

In conclusion, to ask about "Native American tribes in Canada" is to open a door to a profound and complex understanding of identity, history, and resilience. It reveals not a monolithic "Native American" presence, but a mosaic of vibrant and distinct nations – First Nations, Inuit, and Métis – each with their own unique stories, challenges, and aspirations. Canada’s future, and its ability to live up to its ideals of justice and equality, hinges on its commitment to meaningful reconciliation, respecting the inherent rights and self-determination of its original peoples, and recognizing the invaluable contributions they make to the rich tapestry of the nation. The journey is long, but the commitment to walking it together, with respect and understanding, is growing stronger.