Echoes in the Red Clay: Unearthing Georgia’s Native American Past

Georgia, the "Peach State," is a land steeped in history, its red clay soil holding centuries of stories. Yet, for many who call it home today, the vibrant, complex history of the Native American nations who once thrived here remains largely unseen, or worse, forgotten. Unlike states in the American West, where federally recognized tribes maintain sovereign lands and a visible presence, Georgia has no such tribes. This absence is not a natural occurrence but a stark testament to one of the most tragic chapters in American history: the forced removal of indigenous peoples.

To understand Georgia, one must first understand the profound Native American legacy etched into its very landscape, from the names of rivers and towns to the ancient mounds that dot the countryside. This article seeks to unearth that history, exploring the rich cultures that flourished here, the forces that led to their displacement, and the enduring echoes that persist today.

A Deep Rooted Presence: Thousands of Years of History

Long before European contact, what we now call Georgia was home to diverse and sophisticated indigenous societies. For over 12,000 years, Native peoples adapted to its varied landscapes, from the Appalachian mountains in the north to the coastal plains in the south. The earliest inhabitants were nomadic hunter-gatherers, but over millennia, their societies evolved, leading to the development of complex agricultural communities.

The Mississippian culture, flourishing from roughly 800 to 1600 CE, left the most impressive physical legacy. These were the mound builders, whose monumental earthworks served as ceremonial centers, burial sites, and platforms for elite residences. Sites like Etowah Mounds near Cartersville and Ocmulgee Mounds in Macon are powerful reminders of these highly organized societies, showcasing intricate social structures, extensive trade networks, and a rich spiritual life. The scale of these constructions suggests a population far greater and more advanced than often portrayed in popular history.

The Great Nations: Cherokee and Muscogee (Creek)

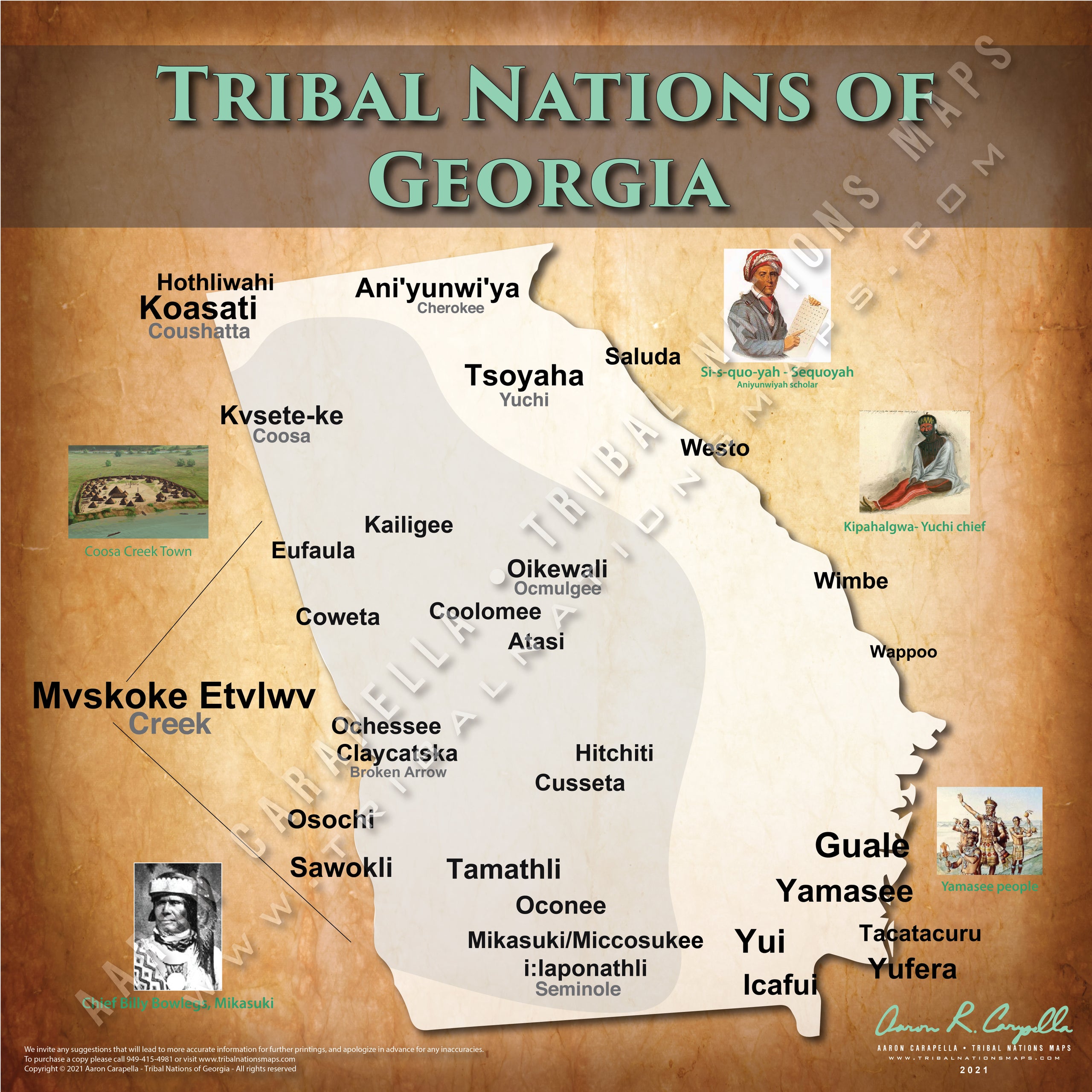

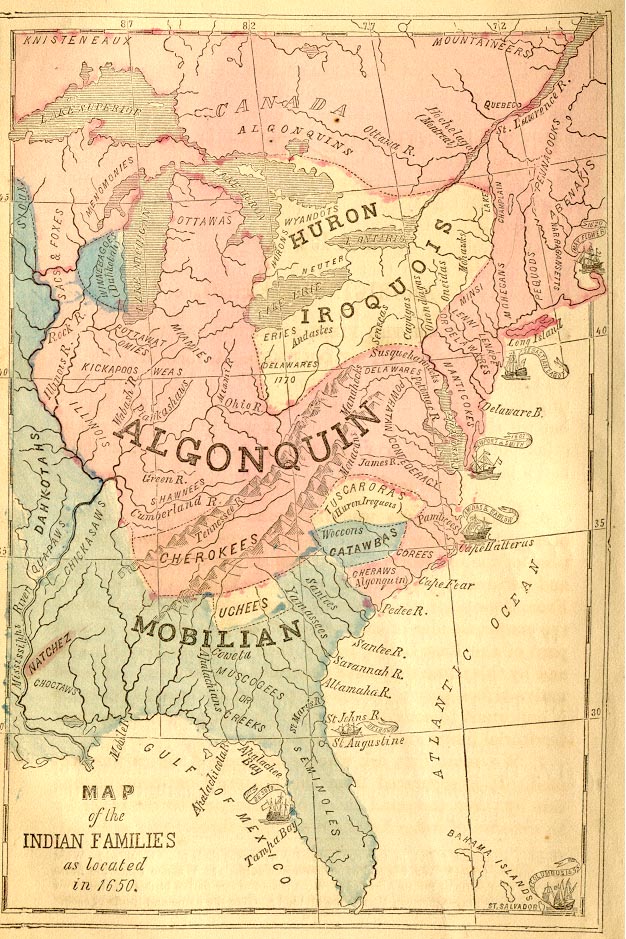

By the time European explorers arrived in the 16th century, two dominant Native American nations had emerged as the primary inhabitants of Georgia: the Cherokee in the mountainous north and the Muscogee, often referred to as the Creek Confederacy, across the central and southern regions.

The Cherokee, known to themselves as the Aniyvwiya (Principle People), were a highly adaptable and strategically positioned nation. Their territory spanned parts of modern-day Georgia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Alabama. Their towns, often situated along rivers, were self-governing, but united by a common language (Iroquoian) and cultural identity. They were skilled farmers, hunters, and craftspeople, renowned for their intricate basketry and pottery.

The Muscogee (Creek) Confederacy was a sprawling, powerful alliance of diverse towns and linguistic groups (primarily Muskogean). They called themselves "Muscogee" and were organized into a sophisticated political and social system, often divided into "White Towns" (peace) and "Red Towns" (war). Their confederacy was a testament to political ingenuity, allowing disparate groups to coexist and collectively defend their vast territories, which stretched across Georgia, Alabama, and parts of Florida. The Muscogee were central to the economic and political landscape of the Southeast, engaging in extensive trade with both other Native nations and, later, European powers.

European Arrival and the Shifting Sands of Power

The arrival of Europeans brought profound and devastating changes. Hernando de Soto’s expedition in 1540, searching for gold, was the first significant European contact, bringing not only violence but also diseases against which Native populations had no immunity. Smallpox, measles, and influenza decimated communities, weakening the very fabric of indigenous societies.

Over the next two centuries, as Spanish, British, and later American interests clashed over control of the Southeast, Native American nations found themselves caught in a precarious balance. They became adept at playing one European power against another, leveraging their strategic positions and military strength to protect their lands and sovereignty. Trade, particularly in deerskins, became vital, but it also integrated Native economies into a colonial system, creating new dependencies.

The "Civilized Tribes" and the Inevitable Conflict

By the early 19th century, the newly formed United States began to exert increasing pressure on Native lands. Driven by a burgeoning population, the cotton boom, and the insatiable demand for land, American settlers encroached steadily. In response, many Native nations, particularly the Cherokee and Creek, adopted aspects of American culture in an attempt to coexist and preserve their sovereignty. They were among the "Five Civilized Tribes" (along with the Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Seminole), a term ironically coined by Americans to describe their perceived progress towards "civilization."

The Cherokee, in particular, embraced these changes with remarkable zeal. They developed a written constitution, established a republican form of government, founded schools, adopted farming techniques, and even published their own newspaper, the "Cherokee Phoenix," using a syllabary invented by Sequoyah. This syllabary, developed in the 1820s, allowed the Cherokee to read and write in their own language, becoming one of the few indigenous peoples to create a fully functional writing system. It was a powerful symbol of their modernity and resilience.

Despite these efforts, and despite treaties affirming their land rights, the state of Georgia’s appetite for Native land grew insatiable, fueled by the discovery of gold in Cherokee territory in 1828 (near present-day Dahlonega). The Gold Rush ignited a fervor that made any form of coexistence seem impossible to Georgian politicians and settlers.

The Indian Removal Act and the Trail of Tears

The stage was set for the ultimate betrayal. President Andrew Jackson, a veteran of wars against Native Americans and a staunch advocate for "Indian Removal," signed the Indian Removal Act into law in 1830. This act authorized the forced relocation of Native Americans from their ancestral lands in the southeastern United States to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma).

The Cherokee fought back through legal means, leading to the landmark Supreme Court case Worcester v. Georgia (1832). Chief Justice John Marshall ruled in favor of the Cherokee, stating that Georgia had no jurisdiction over Cherokee lands and that the Cherokee Nation was a "distinct community, occupying its own territory… in which the laws of Georgia can have no force." Famously, President Jackson reportedly defied the ruling, declaring, "John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it."

Despite the Supreme Court victory, a small faction of the Cherokee, known as the Treaty Party (led by Elias Boudinot and Major Ridge), believing resistance was futile, signed the Treaty of New Echota in 1835 without the consent of the majority of the Cherokee Nation or its principal chief, John Ross. This illegitimate treaty ceded all Cherokee lands east of the Mississippi in exchange for land in Indian Territory and monetary compensation.

The vast majority of the Cherokee Nation refused to recognize the treaty. Nevertheless, it provided the legal pretext for their removal. In the brutal winter of 1838-1839, under the command of General Winfield Scott, approximately 16,000 Cherokee men, women, and children were forcibly rounded up from their homes in Georgia and other southeastern states and marched more than a thousand miles west. This forced migration, often undertaken on foot with minimal provisions, became known as the Trail of Tears. Over 4,000 Cherokee perished from disease, starvation, and exposure along the way.

The Muscogee (Creek) Nation had faced a similar fate earlier. Following the Creek War of 1813-1814 and the Treaty of Fort Jackson (1814), where Andrew Jackson seized vast tracts of Creek land, and further land cessions orchestrated by figures like William McIntosh (who was later executed by his own people for ceding tribal lands without authorization), the majority of the Muscogee were also forcibly removed to Indian Territory in the 1830s.

The Void and the Echoes Today

The forced removal left a profound void in Georgia. The land, once teeming with vibrant indigenous cultures, was now open for white settlement and the expansion of the cotton kingdom and slavery. The narrative of an "empty" wilderness ready for American civilization took hold, effectively erasing the memory of the Native American presence from public consciousness for generations.

Today, there are no federally recognized Native American tribes in Georgia. This does not mean, however, that Native American history or people are absent. Many geographic names – Chattahoochee, Oconee, Savannah, Tallulah – are enduring linguistic legacies of the indigenous languages spoken here. Historical markers and state parks like New Echota Historic Site (the capital of the Cherokee Nation before removal) and the aforementioned mound sites serve as somber reminders of a rich past.

Furthermore, while no federally recognized tribes exist within Georgia’s borders, thousands of individuals with Native American ancestry live in the state. Many are descendants of those who managed to evade removal, or who returned later, or are part of the broader Native American diaspora from tribes across the continent. These individuals and their families often work tirelessly to preserve their heritage, language, and traditions, often through community organizations, cultural centers, and educational initiatives. Pow-wows and cultural events are held regularly, providing spaces for intertribal connection and the sharing of traditions.

Remembering and Reconciling

The story of Native American tribes in Georgia is a complex and often painful one, a testament to resilience in the face of immense injustice. It challenges the romanticized narratives of American expansion and forces us to confront the moral costs of nation-building.

As Dr. Gregory D. Smithers, a historian of Native American history, notes, "The history of Native Americans in Georgia isn’t just about what was lost, but about what endures. It’s about the spirit of people who, despite forced removal and cultural suppression, continue to reclaim their heritage and remind us of the deep roots they have in this land."

For Georgia to truly understand itself, it must acknowledge this foundational history. By visiting ancient mound sites, learning about the Cherokee Syllabary, or simply reflecting on the indigenous names that pepper the map, Georgians can begin to unearth the echoes of the past. It is a vital step toward a more complete understanding of American history and a necessary act of remembrance for the nations whose vibrant cultures once defined the landscape of the Peach State. The red clay remembers, and so, too, must we.