Echoes in the Prairie: Unearthing Illinois’ Native American Heritage

SPRINGFIELD, IL – The name "Illinois" itself whispers of its ancient past. Derived from "Illiniwek," meaning "people of the Illini," or simply "men" in the Algonquian language, it serves as a subtle yet persistent reminder that this land, now defined by sprawling cities, vast farmlands, and bustling highways, was once the vibrant heartland of diverse and sophisticated Native American civilizations. Their stories, often overshadowed by subsequent colonial narratives, are etched into the very soil, waiting to be rediscovered.

For centuries before European contact, the Illinois landscape was a mosaic of tribal territories, each with unique cultures, languages, and lifeways. From the monumental earthworks of Cahokia to the semi-nomadic hunting grounds of the Kickapoo, the spiritual connections and societal structures of these Indigenous peoples shaped the land long before settlers envisioned a state. Today, while no federally recognized tribes reside within Illinois’ borders, their legacy is far from erased. It persists in archaeological sites, place names, and the ongoing efforts of descendants to reclaim and revitalize their heritage.

The Dawn of Civilization: Cahokia Mounds

To truly understand Illinois’ Indigenous history, one must begin not with European explorers, but with the colossal urban center that predated them by centuries: Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site, a UNESCO World Heritage site just outside modern-day Collinsville. Around 1050 CE, this area blossomed into the largest pre-Columbian city north of Mexico, a sprawling metropolis that once housed an estimated 10,000 to 20,000 people, and perhaps up to 40,000 at its peak.

"Cahokia represents an extraordinary level of societal complexity, urban planning, and agricultural prowess," explains Dr. Tim Pauketat, an archaeologist and professor at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, whose work has extensively focused on the site. "It was a major trade hub, a political and religious center, with monumental architecture like Monks Mound, which is larger at its base than the Great Pyramid of Giza." This massive earthen platform, reaching 100 feet in height, once supported a grand temple or the residence of a powerful leader, overlooking a meticulously planned city with plazas, residential areas, and sophisticated astronomical alignments, such as "Woodhenge," a series of timber circles used to track solstices and equinoxes.

The people of Cahokia, part of the Mississippian culture, were master farmers, cultivating vast fields of maize, squash, and beans, which supported their dense population. Their influence spread across the Midwest, evident in the shared ceramic styles, iconography, and mound-building traditions found far from Cahokia itself. Yet, by the 14th century, Cahokia experienced a gradual decline and eventual abandonment, the reasons for which are still debated among scholars, ranging from environmental degradation and resource depletion to internal strife or shifting political dynamics. Its fall, however, did not signify an end to Indigenous life in Illinois, but rather a transformation, paving the way for new tribal configurations.

The Illiniwek Confederacy: Guardians of the Prairies

By the time French explorers Jacques Marquette and Louis Joliet paddled down the Mississippi River in 1673, the dominant power in the region was the Illiniwek Confederacy. This alliance of several Algonquian-speaking tribes – including the Kaskaskia, Cahokia (a distinct tribe from the ancient city’s inhabitants), Peoria, Michigamea, Moingwena, and Tamaroa – controlled a vast territory stretching across much of present-day Illinois, parts of Iowa, Missouri, and Arkansas.

"The Illiniwek were highly organized, living in large, semi-permanent villages along major rivers like the Illinois and Mississippi," notes Dr. Susan Schanck, an ethnohistorian specializing in Native American cultures of the Great Lakes region. "They were expert hunters, particularly of bison and deer, but also practiced extensive agriculture, growing corn, beans, and squash. Their social structures were complex, with clear leadership roles, spiritual traditions, and a deep understanding of their environment."

The arrival of the French marked a pivotal moment. Unlike the British, who primarily sought land for settlement, the French were initially interested in trade and alliances, particularly for furs. The Illiniwek, eager for European goods like tools, firearms, and textiles, formed a complex, often fragile, relationship with the newcomers. Father Marquette described the Kaskaskia as "a very numerous nation, divided into several villages" and noted their "hospitable" nature. This early interaction established a fur trade network that, while bringing new technologies, also introduced devastating European diseases like smallpox and measles, to which Native populations had no immunity. These epidemics decimated Illiniwek numbers, weakening their confederacy and making them more vulnerable to encroachment.

A Shifting Tide: Conflict and Displacement

As the 18th century progressed, the balance of power in Illinois shifted dramatically. The French and Indian War (1754-1763) saw France cede its North American territories to Great Britain. With the American Revolution, British influence waned, and the newly formed United States began its relentless westward expansion. This period was marked by escalating conflict, broken treaties, and the systematic dispossession of Native lands.

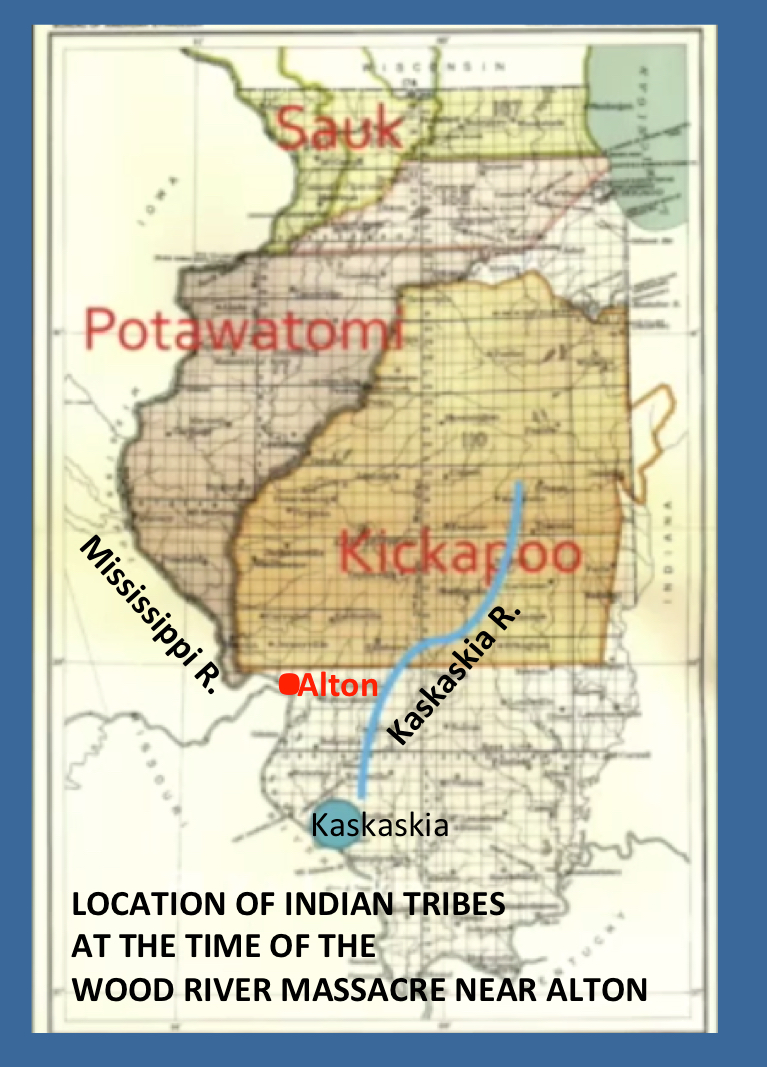

The Illiniwek, already weakened by disease and inter-tribal warfare exacerbated by the fur trade, found themselves caught between powerful forces. Tribes from the east, displaced by American settlement, began migrating into Illinois, including the Potawatomi, Kickapoo, Sauk (Sac), and Meskwaki (Fox). These tribes, often with different political agendas and alliances, further complicated the landscape.

The early 19th century witnessed a rapid succession of treaties, often signed under duress or with leaders who did not represent the full consensus of their people. The Treaty of St. Louis (1804), for instance, saw the Sauk and Fox cede vast tracts of land in Illinois and Missouri, a treaty many tribal members disputed, claiming their representatives had been coerced or lacked proper authority. This simmering resentment would eventually boil over.

The Black Hawk War: A Tragic Last Stand

The Black Hawk War of 1832 stands as a tragic testament to the futility of Native resistance against overwhelming American expansion. Led by the Sauk warrior Black Hawk, a coalition of Sauk, Fox, and Kickapoo people, including women, children, and elders, attempted to return to their ancestral lands near their village of Saukenuk (present-day Rock Island, Illinois) after being forcibly removed west of the Mississippi River. Black Hawk sought to plant corn and live peacefully, but American settlers and the militia saw their return as an invasion.

"The Black Hawk War wasn’t just a battle for land; it was a fight for a way of life, for cultural survival," states Dr. John Red Cloud, a descendant of a Black Hawk War participant and a Native American studies scholar. "Black Hawk believed they had a right to their homes, to their sacred burial grounds, and to the land that sustained them for generations."

The conflict was brutal and short-lived. Despite initial successes, Black Hawk’s band, outnumbered and outgunned, was relentlessly pursued. The war culminated in the horrific Bad Axe Massacre on August 2, 1832, where hundreds of Sauk and Fox, including women and children attempting to flee across the Mississippi River, were slaughtered by American forces. Black Hawk himself was captured, and the remaining Indigenous populations in Illinois were swiftly removed. His poignant surrender speech, delivered later, encapsulated the despair: "I fought hard for my people… The white men are bad schoolmasters; they have taught us nothing but trouble."

The "Empty Land" Myth and Enduring Legacies

Following the Black Hawk War and the Indian Removal Act of 1830, virtually all Native American tribes were forcibly removed from Illinois, primarily to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) and Kansas. This created the enduring, yet false, narrative that Illinois was an "empty" land, ripe for settlement, its Indigenous past conveniently erased.

"The idea of an ’empty’ or ‘virgin’ wilderness was a convenient fiction that justified manifest destiny and dispossession," explains Dr. Rebecca Tsosie, a legal scholar specializing in Indigenous peoples’ rights. "It ignored millennia of human habitation, sophisticated land management, and deep cultural connections to the environment."

Yet, the legacy of Illinois’ Native American tribes persists. Their descendants, now primarily residing in Oklahoma, Kansas, and other states, maintain vibrant cultures, often through federally recognized entities like the Peoria Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma (descendants of the Illiniwek), the Sac and Fox Nation (Oklahoma and Kansas), the Kickapoo Tribe of Oklahoma, and the Citizen Potawatomi Nation. These tribes, despite the trauma of forced removal, have actively worked to preserve their languages, traditions, and governance structures.

In Illinois itself, efforts are underway to acknowledge and educate. Museums like the Illinois State Museum and the Field Museum in Chicago house extensive collections of Native American artifacts, striving to present a more accurate and nuanced history. Universities are increasingly incorporating Indigenous perspectives into their curricula and promoting land acknowledgements to recognize the original inhabitants of the land. Public awareness campaigns aim to dispel myths and highlight the ongoing contributions of Native peoples.

The echoes of the prairie’s original inhabitants are not merely historical footnotes. They are a living testament to resilience, cultural endurance, and an unbroken connection to the land. As Illinois continues to grow and evolve, recognizing and honoring its deep Indigenous roots is not just an act of historical correction, but a vital step towards a more complete and just understanding of its identity. The whispers of the Illiniwek, the silent mounds of Cahokia, and the tragic lessons of the Black Hawk War serve as powerful reminders that Illinois’ story is inextricably woven with the rich, complex, and enduring heritage of its first peoples.