Beyond the Prairies: Iowa’s Enduring Native American Legacy

Iowa, often painted with strokes of amber waves of grain and bustling agricultural landscapes, holds a deeper, older story etched into its very soil – a narrative of resilience, displacement, and enduring heritage belonging to its First Nations. While the state is now primarily known for its cornfields and the Hawkeye football team, long before European settlers arrived, this fertile land between the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers was the ancestral home to a vibrant tapestry of Native American tribes. Their history, though often overlooked in mainstream accounts, is crucial to understanding Iowa’s true identity.

The story of Native Americans in Iowa is not merely one of ancient history; it is a living testament to survival against immense odds, a struggle for sovereignty, and a vibrant cultural resurgence. From the earliest mound builders to the unique self-purchase of land by the Meskwaki Nation, and the lingering echoes of tribes forced westward, Iowa’s Indigenous past and present are intertwined in a compelling saga.

The Original Inhabitants: A Land of Abundance

Thousands of years before European contact, Iowa’s landscape was a rich mosaic of prairies, forests, and wetlands, crisscrossed by mighty rivers. This environment supported diverse Indigenous cultures. Early inhabitants, known as the Mound Builders, left behind intricate effigy mounds, particularly visible at Effigy Mounds National Monument in northeastern Iowa. These sacred earthworks, often shaped like animals, served as burial sites and ceremonial grounds, offering a glimpse into the sophisticated spiritual and social lives of ancient peoples.

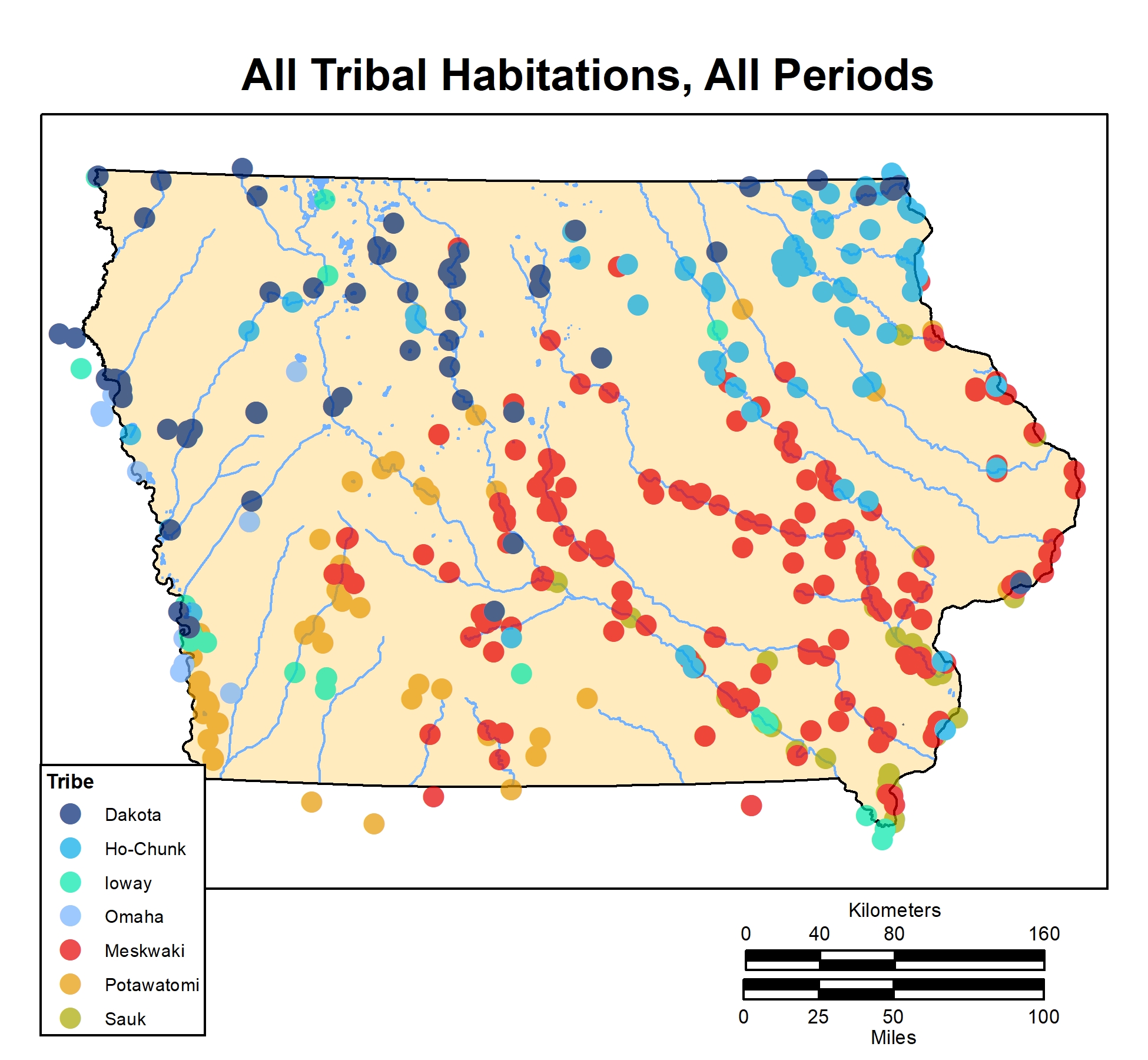

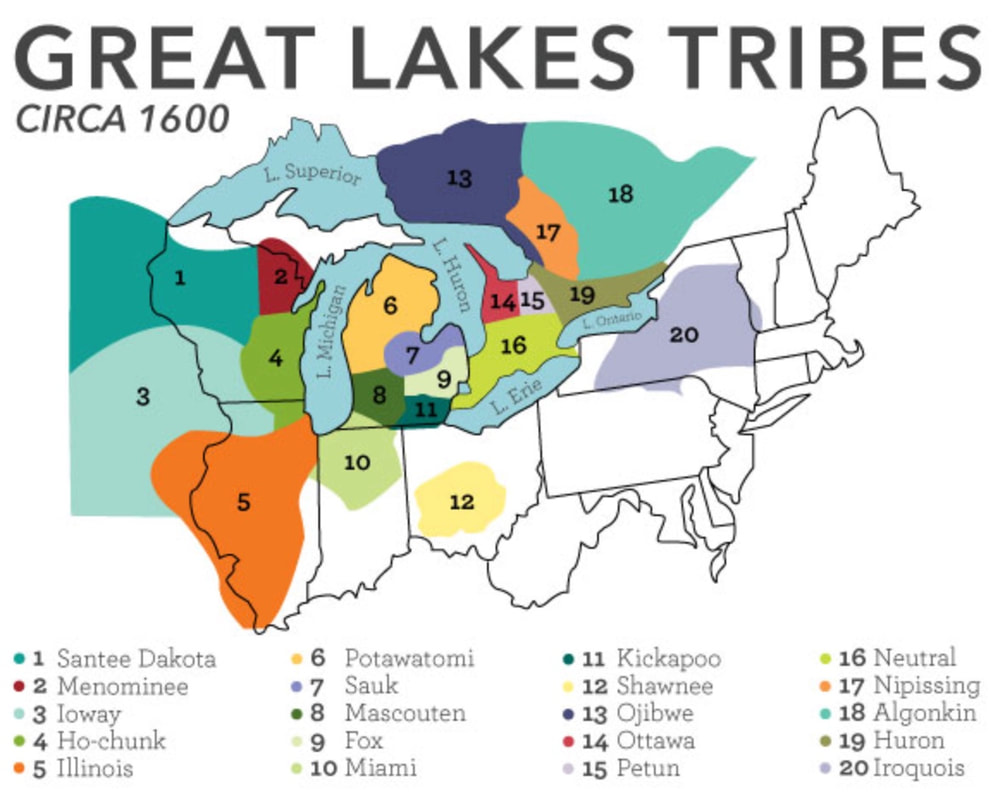

By the 17th century, when French explorers Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet traversed the Mississippi River, numerous distinct tribes inhabited what would become Iowa. Among the most prominent were the Ioway (or Iowa) people, who gave the state its name, the Sac (Sauk) and Fox (Meskwaki) nations, the Potawatomi, the Omaha, the Otoe, the Missouri, and various bands of the Dakota Sioux in the western and northern regions.

Each tribe possessed a unique language, social structure, and way of life, adapted to the specific resources of their territories. The Sac and Fox, for instance, were known for their agricultural prowess, cultivating corn, beans, and squash, while also engaging in extensive hunting and trapping. The Dakota Sioux, on the other hand, were more nomadic, following buffalo herds across the plains. Despite their differences, all shared a deep spiritual connection to the land, viewing it not as property to be owned but as a sacred trust to be stewarded.

The Era of Treaties and Dispossession

The 19th century brought an era of relentless pressure and profound change for Iowa’s Native populations. Following the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the United States government embarked on an aggressive policy of westward expansion, fueled by the concept of "Manifest Destiny." This expansion invariably led to conflicts over land and resources.

The primary tool for acquiring Native lands was the treaty, often negotiated under duress, with promises that were rarely kept. Between 1830 and 1851, a series of treaties systematically dispossessed tribes of their ancestral territories in Iowa. The Sac and Fox, in particular, were forced to cede vast tracts of land, moving progressively westward. Their resistance culminated in the tragic Black Hawk War of 1832, a desperate attempt by Sac leader Black Hawk to reclaim ancestral lands in Illinois and Iowa. The conflict ended in a decisive defeat for Black Hawk’s band, leading to further land cessions and their eventual forced removal across the Mississippi.

"The treaty process was designed to dispossess us," explains Dr. Lori A. Fuller, a historian specializing in Native American history. "It was rarely a negotiation between equals. Tribes were often pressured, deceived, or faced with impossible choices: cede land or face military might."

Other tribes met similar fates. The Ioway, Omaha, Otoe, and Missouri peoples were pushed into reservations in Nebraska, Kansas, and Oklahoma. The Dakota Sioux, after conflicts like the Spirit Lake Massacre in 1857, were largely confined to reservations in the Dakotas and Minnesota. By the mid-1800s, it seemed as though Iowa would be entirely devoid of its Indigenous inhabitants, fulfilling the government’s removal policy.

The Meskwaki Exception: A Story of Self-Determination

Amidst this widespread displacement, one tribe achieved a remarkable feat of self-determination: the Meskwaki Nation, also known as the Sac and Fox of the Mississippi in Iowa. Unlike other tribes who were forcibly removed to reservations far from their homelands, the Meskwaki took a unique and unprecedented step.

In 1857, utilizing funds from annuities owed to them by treaty and from selling their personal belongings, the Meskwaki collectively purchased 80 acres of land near the Iowa River in Tama County. This act was revolutionary. It was the first time a Native American tribe had purchased land from the U.S. government, rather than being granted a reservation. This land, known as the Meskwaki Settlement, became a refuge for those who refused to abandon their ancestral territory and cultural identity.

"Our ancestors had the foresight and the courage to say, ‘We will not be moved further. We will stay here, on our own terms,’" states a Meskwaki elder, reflecting on their history. "That act of buying back our land is the foundation of our sovereignty today. It’s who we are."

The Meskwaki Settlement grew over time, as the tribe continued to purchase adjacent lands, eventually encompassing thousands of acres. This independent ownership allowed the Meskwaki to maintain a stronger connection to their traditions, language, and governance structure, resisting assimilation efforts more effectively than many other tribes.

Contemporary Life: Resilience and Revitalization

Today, the narrative of Native Americans in Iowa is one of ongoing revitalization and determination. While the Meskwaki Nation is the only federally recognized tribe with a land base in Iowa, the state is also home to thousands of individuals from various tribal nations, including descendants of the Ioway, Potawatomi, and Sioux, whose ancestors once roamed these lands.

The Meskwaki Nation, with a population of over 1,400 members on their settlement, stands as a beacon of Indigenous sovereignty. They operate their own tribal government, schools, police force, and health services. A significant driver of their economic self-sufficiency is the Meskwaki Bingo Casino Hotel, which opened in 1992. Gaming revenue has allowed the tribe to invest in infrastructure, education, and cultural preservation programs, creating opportunities for their community.

"The casino is not just about gambling; it’s about our future," explains a tribal council member. "It provides jobs, funds our essential services, and allows us to reclaim our self-determination. It’s a tool for our sovereignty."

Cultural preservation is a paramount focus for the Meskwaki. The Meskwaki language, an Algonquian dialect, is actively taught to younger generations through immersion programs to ensure its survival. Traditional ceremonies, storytelling, and the annual Meskwaki Powwow – a vibrant celebration of dance, music, and community – serve as vital platforms for transmitting cultural knowledge and pride.

However, challenges persist. Like many Native American communities across the U.S., the Meskwaki and other Indigenous peoples in Iowa face disparities in health outcomes, education, and economic opportunity, often stemming from generations of historical trauma, systemic discrimination, and underfunding. Issues such as diabetes, substance abuse, and access to quality healthcare remain pressing concerns.

Looking Forward: Acknowledgment and Understanding

The story of Native Americans in Iowa is far from over. It is a dynamic, evolving narrative of people who have survived immense historical injustices and continue to thrive. Acknowledging this complex history – the pre-contact flourishing, the devastating impact of removal, and the remarkable acts of resistance and reclamation – is essential for all Iowans.

Educational initiatives are slowly working to incorporate more accurate and comprehensive Native American history into school curricula. Events like the annual Native American Powwow at the University of Iowa and community programs aim to foster greater understanding and appreciation of Indigenous cultures.

The enduring presence and contributions of Native American tribes in Iowa serve as a powerful reminder that history is not static. It is a living force that shapes the present and informs the future. By recognizing and honoring the rich heritage and ongoing resilience of Iowa’s First Nations, the state can move towards a more inclusive and truthful understanding of its own identity, fostering respect and collaboration for generations to come. The voices of Iowa’s original inhabitants echo across the prairies, a testament to an unbreakable spirit and an enduring legacy.