Guardians of the Great Lakes: The Enduring Legacy of Michigan’s Native American Tribes

By [Your Name/Journalist’s Name]

Michigan, a state synonymous with its iconic Great Lakes and vast forests, holds a history far deeper and more complex than its industrial past or tourism brochures often suggest. Beneath the surface of its modern identity lies the vibrant, enduring legacy of its first inhabitants – the Native American tribes whose roots stretch back millennia. These are not just figures from history books; they are sovereign nations, resilient communities, and vital contributors to the state’s cultural, economic, and environmental fabric, their voices echoing across generations, reminding us that they are still here, still thriving.

For centuries before European contact, the lands now known as Michigan were home to the Anishinaabek, or the "original people," a collective term for the Ojibwe (Chippewa), Odawa (Ottawa), and Potawatomi nations. These three distinct but closely related tribes formed the historic Council of Three Fires, a powerful political and cultural alliance that governed vast territories around the Great Lakes. Their lives were intrinsically woven with the natural world, their cultures rich with oral traditions, intricate social structures, and sustainable practices for hunting, fishing, gathering, and agriculture. They were stewards of the land, understanding the delicate balance of ecosystems long before the concept was articulated in modern science.

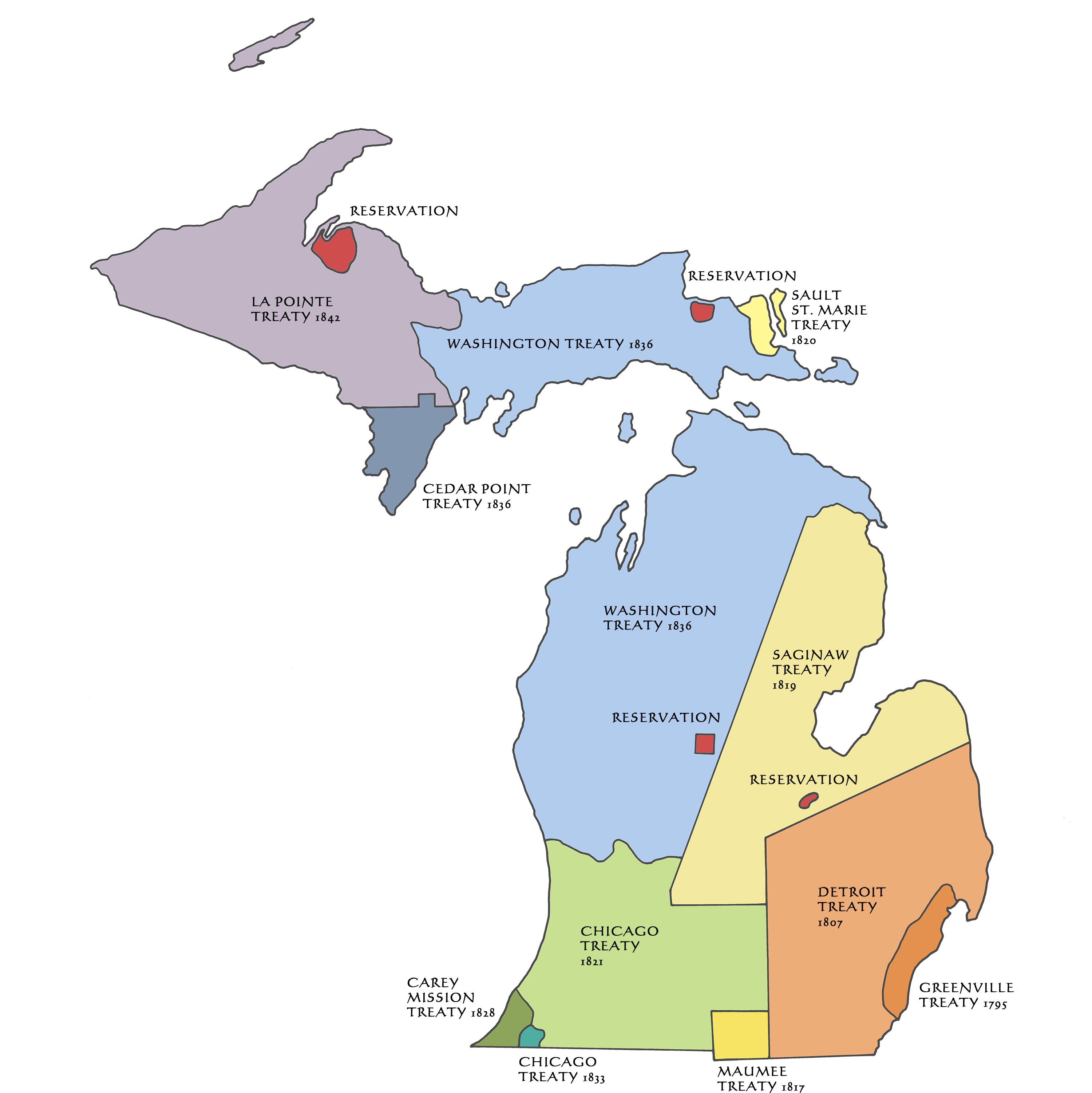

The arrival of European fur traders, missionaries, and eventually settlers brought profound and often devastating changes. Alliances were formed, trade flourished, but so too did disease, conflict, and the relentless pressure for land. Treaties, often signed under duress or through deception, systematically dispossessed tribes of their ancestral territories. The Treaty of Washington in 1836, for instance, ceded an estimated 13.8 million acres of land in Michigan to the U.S. government, leaving tribes with small, fragmented reservations. The infamous "Trail of Death" saw the forced removal of Potawatomi people from Michigan and Indiana to Kansas in 1838, a brutal chapter in American history that claimed hundreds of lives.

Yet, despite these traumatic experiences and concerted efforts at assimilation, Michigan’s Native American communities demonstrated remarkable resilience. Many refused to leave their homelands, adapting to new circumstances while fiercely guarding their cultural heritage. They persevered through periods of governmental neglect, the termination era of the mid-20th century which sought to dismantle tribal governments, and the ongoing struggle against stereotypes and systemic discrimination.

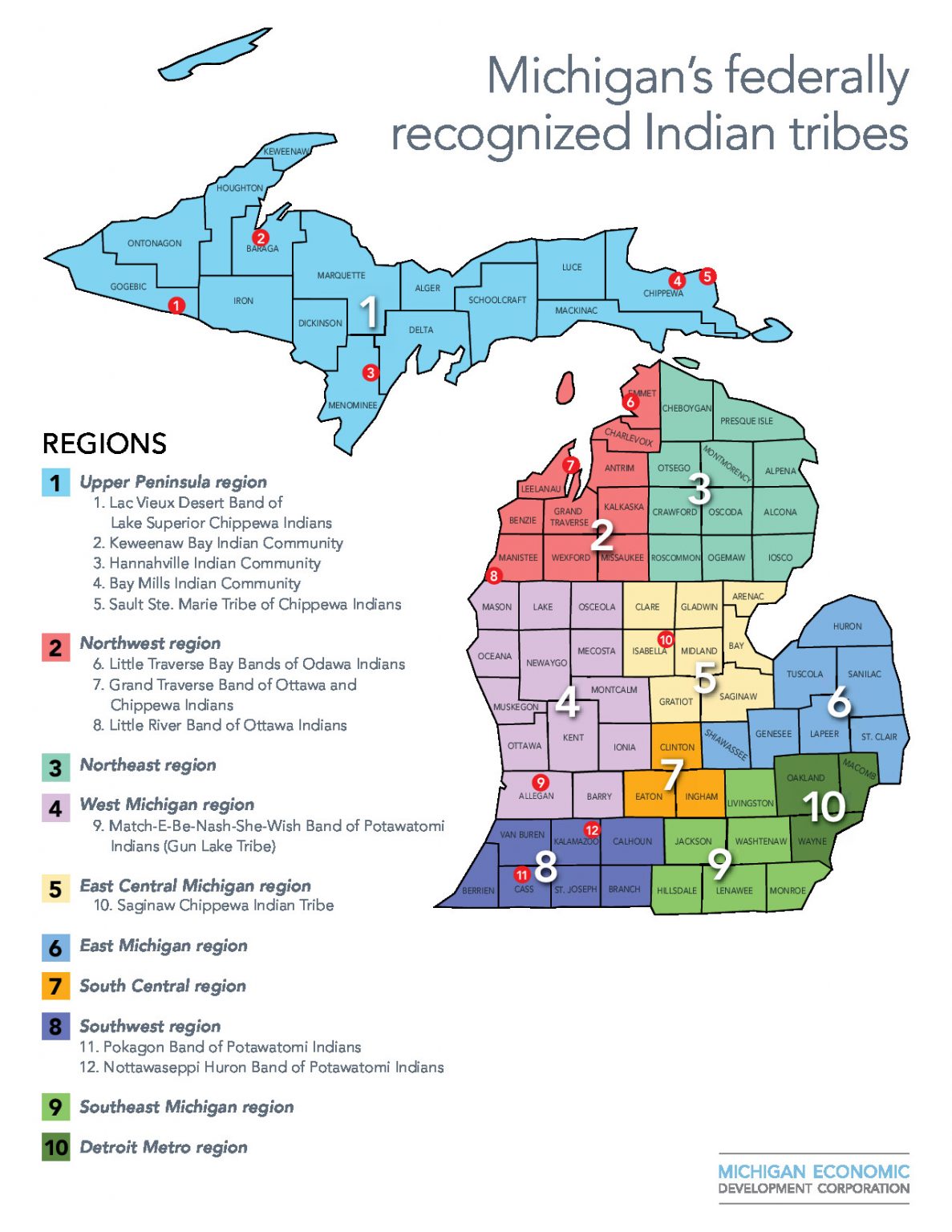

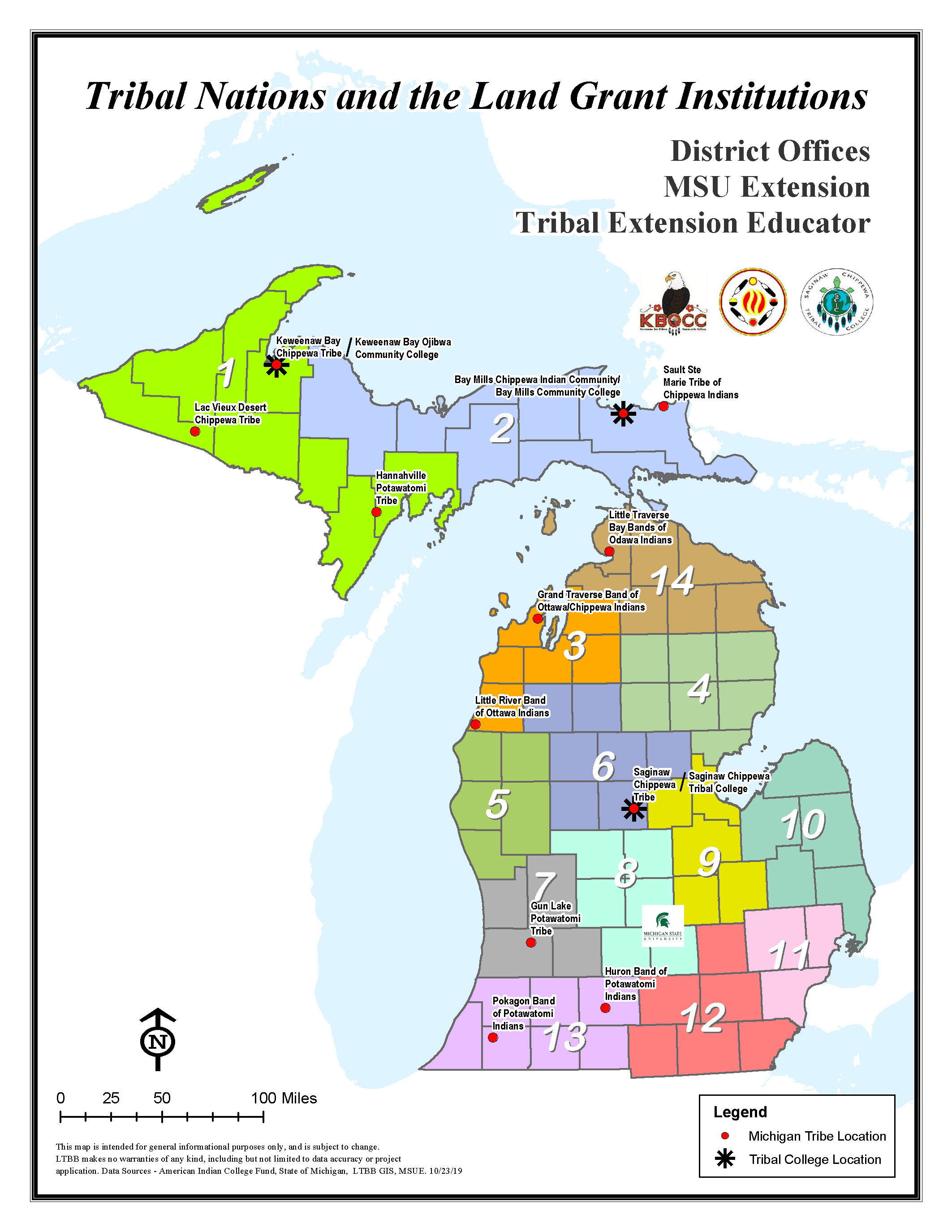

Today, Michigan is home to 12 federally recognized Native American tribes, each a sovereign nation with its own government, laws, and distinct cultural practices. These include:

- Bay Mills Indian Community

- Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians

- Hannahville Indian Community

- Keweenaw Bay Indian Community

- Lac Vieux Desert Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians

- Little River Band of Ottawa Indians

- Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians

- Match-E-Be-Nash-She-Wish Band of Pottawatomi Indians (Gun Lake Tribe)

- Nottawaseppi Huron Band of Potawatomi

- Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians

- Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe of Michigan

- Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians

The concept of sovereignty is central to understanding these tribes. It means they possess the inherent right to self-governance, to determine their own membership, to establish their own laws, and to operate their own judicial systems. This is not a right granted by the state or federal government, but one that pre-dates the formation of the United States itself. As Aaron Payment, former Chairman of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians, one of the largest tribes in Michigan, once articulated, "Sovereignty is about self-determination. It’s about being able to make decisions for our people, by our people, to preserve our culture and ensure a better future."

A significant turning point for many tribes came with the advent of tribal gaming. While often misunderstood as simple casinos, these enterprises are far more than just entertainment venues. They are powerful economic engines, a direct result of tribal sovereignty, enabling tribes to generate revenue independent of federal or state appropriations. The economic impact is profound: tribal governments in Michigan collectively employ thousands of people, both Native and non-Native, and contribute billions of dollars annually to the state’s economy through wages, taxes, and purchases.

Beyond the gaming floor, these revenues are reinvested directly into tribal communities. They fund essential services that often fill gaps left by inadequate state or federal funding, including:

- Healthcare: Operating clinics, addressing health disparities, and providing access to medical and dental care.

- Education: Funding schools, scholarships for higher education, language immersion programs, and cultural preservation initiatives.

- Infrastructure: Building housing, roads, water treatment facilities, and community centers.

- Social Services: Programs for elders, youth, mental health, and addiction recovery.

- Economic Diversification: Investing in non-gaming businesses like hotels, resorts, agriculture, and manufacturing, ensuring long-term sustainability.

For instance, the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians, based in Dowagiac, has used its economic success not only to provide extensive services for its citizens but also to reacquire ancestral lands, strengthening their connection to the past and providing a foundation for future generations. The Little River Band of Ottawa Indians near Manistee has similarly diversified its economy and actively works on environmental protection, a core tenet of Anishinaabek philosophy.

Cultural revitalization is a vibrant and ongoing effort within Michigan’s tribes. After generations of suppression, there is a powerful resurgence of interest in language, traditions, and ceremonies. Anishinaabemowin (the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi language) is being taught in tribal schools and community centers, recognized as a critical link to identity and knowledge. Powwows, vibrant celebrations of dance, song, and community, are held throughout the year, open to the public and serving as powerful expressions of cultural pride and continuity. Traditional arts, such as quillwork, beadwork, and birchbark crafting, are being preserved and passed down.

Environmental stewardship remains a cornerstone of tribal identity. Many tribes are actively involved in protecting Michigan’s natural resources, advocating for clean water, healthy forests, and sustainable fishing practices. They often lead efforts to restore native habitats and manage natural resources in ways that reflect their traditional ecological knowledge, often partnering with state and federal agencies to achieve these goals. Their deep spiritual connection to the land and water—often summarized by the phrase "Nibi is Life" (Water is Life)—drives their advocacy for environmental justice.

Despite their significant progress and contributions, Michigan’s Native American tribes continue to face challenges. Historical trauma, including the lingering effects of forced assimilation, poverty, and discrimination, contributes to disproportionate rates of certain health conditions and social issues. Misconceptions and a lack of public awareness about tribal sovereignty, history, and contemporary life also persist. Many Michiganders are unaware that these vibrant, self-governing nations exist within their state, let alone the depth of their contributions.

Educating the broader public is crucial. Efforts are underway in many tribal communities and by organizations like the Michigan Indian Education Council to ensure that Native American history is accurately and comprehensively taught in schools, moving beyond simplistic narratives to embrace the complexity, resilience, and ongoing contributions of Indigenous peoples. This includes acknowledging the land on which we live and work, recognizing the Indigenous peoples who have stewarded it for millennia.

As Michigan looks to its future, the enduring presence and sovereignty of its Native American tribes are not just historical footnotes but living realities. They represent a testament to an unbreakable spirit, a commitment to cultural preservation, and a powerful model of self-determination. Their voices, their wisdom, and their deep connection to the land and water are invaluable assets for the entire state. Understanding and respecting their legacy is not merely an act of historical acknowledgment, but an essential step toward a more just, equitable, and culturally rich Michigan for all. The guardians of the Great Lakes are still here, and their story continues to unfold, vibrant and resilient as the waters that define their ancient homelands.