Echoes on the Plains: The Enduring Spirit of Native American Tribes in Texas

By [Your Name/Journalist’s Pen Name]

Texas, a land of vast plains, rugged mountains, and meandering rivers, tells a story far older than its iconic Lone Star flag. It’s a narrative deeply etched by the footsteps of its first inhabitants – the diverse Native American tribes who thrived here for millennia. From the sophisticated agriculturalists of East Texas to the nomadic equestrian empires of the West, these indigenous peoples shaped the landscape, culture, and very destiny of what would become the 28th U.S. state. Their history in Texas is a complex tapestry woven with threads of vibrant culture, fierce resistance, devastating loss, and remarkable resilience.

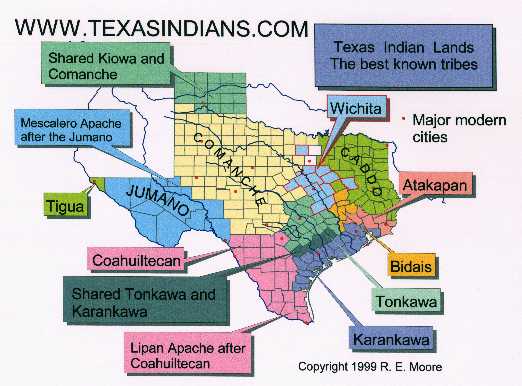

For centuries before European contact, Texas was a mosaic of distinct tribal nations. The Caddo, renowned for their advanced agricultural practices and complex social structures, built elaborate mound cities in the piney woods of East Texas, cultivating corn, beans, and squash. Their trade networks extended across the continent. To the south, along the Gulf Coast, lived the Karankawa and Coahuiltecan, nomadic hunter-gatherers who adapted ingeniously to the coastal environment, navigating their dugout canoes and relying on the abundant marine life.

The central and western plains were dominated by powerful equestrian tribes: the Comanche, Apache, and Wichita. The Comanche, arriving later but quickly asserting dominance, became the undisputed "Lords of the Plains." Their mastery of horsemanship and strategic warfare allowed them to control a vast empire known as "Comancheria," stretching from Kansas to northern Mexico. "Their power was absolute on the plains," notes historian S.C. Gwynne in Empire of the Summer Moon, detailing how the Comanche’s military prowess and economic might made them a formidable force, dictating terms to both other tribes and encroaching European powers.

The Dawn of Conflict and Catastrophe

The arrival of Europeans – first the Spanish in the 16th century, followed by the French, and later Anglo-Americans – irrevocably altered the lives of Texas’s native peoples. The Spanish introduced horses, which revolutionized life for plains tribes, but also brought devastating diseases like smallpox, measles, and influenza. Lacking immunity, entire villages were decimated. Historians estimate that disease wiped out up to 90% of some indigenous populations within a few generations.

The Spanish established missions and presidios, aiming to "civilize" and convert Native Americans to Catholicism and sedentary agricultural life. While some tribes, like the Coahuiltecan, sought refuge in missions from hostile neighbors or economic hardship, many resisted fiercely. The Comanche and Apache, in particular, viewed the Spanish as invaders, launching relentless raids on settlements and missions. This period marked the beginning of centuries of conflict over land, resources, and sovereignty.

With Mexican independence in 1821 and the subsequent Anglo-American colonization of Texas, the pressure on Native American lands intensified. Stephen F. Austin, known as the "Father of Texas," initially sought to negotiate treaties, but the sheer volume of American settlers pushing westward made peaceful coexistence increasingly difficult. The Republic of Texas, established in 1836, ushered in a new era of aggressive expansion.

Mirabeau B. Lamar, the second president of the Republic of Texas, epitomized this hardened stance. Unlike his predecessor Sam Houston, who advocated for diplomacy and treaties, Lamar pursued a policy of "total expulsion" of Native Americans from Texas. His administration launched military campaigns that drove many tribes, including the Cherokee who had settled peacefully in East Texas, across the Red River into Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). The infamous "Cherokee War" of 1839 saw the expulsion of the Cherokee, despite their leader Chief Bowles (Duwali) holding a valid land treaty with Sam Houston.

The Vanishing Act: Tribes Erased and Relocated

By the mid-19th century, with Texas now a U.S. state, the "Indian Wars" escalated. The U.S. Army, often aided by Texas Rangers, waged relentless campaigns against the remaining free-ranging tribes. The buffalo, central to the economy and culture of the plains tribes, were systematically hunted to near extinction, a deliberate strategy to break Native American resistance. The iconic figure of Quanah Parker, the last war chief of the Comanche and son of a captured Anglo settler, Cynthia Ann Parker, symbolizes this era. He led his people in fierce resistance for years before finally surrendering in 1875, marking the end of the Comanche’s long reign on the plains.

Most Texas tribes were eventually removed to reservations in Oklahoma. The Caddo, Wichita, Tonkawa, and most Apache bands found themselves dispossessed of their ancestral lands, forced to adapt to new environments and policies far from their homes. The Karankawa and Coahuiltecan, already decimated by disease and conflict, largely disappeared as distinct cultural groups, assimilated into the broader Hispanic population or succumbing to the harsh realities of displacement. Texas became unique among Western states for having almost no federally recognized Indian reservations within its borders.

The Resurgence: Three Sovereign Nations Endure

Despite this devastating history of removal and attempted erasure, a remarkable story of survival and resurgence emerged. Today, three federally recognized Native American tribes call Texas home, each with a unique and compelling narrative of perseverance:

-

The Ysleta del Sur Pueblo (Tigua): Located in El Paso, the Tigua people are the oldest continuous inhabitants of Texas. Their journey to Texas began not with forced removal from Texas, but to it. In 1680, during the Pueblo Revolt against Spanish rule in New Mexico, loyal Pueblo people, including the Tigua, fled south with the Spanish colonists to what is now Ysleta, Texas. They maintained their distinct Pueblo culture, language (Tiwa), and traditions for centuries, often overlooked by the state. After a long fight, they finally achieved federal recognition in 1987. "Our history is deeply rooted in this land, a testament to our ancestors’ resilience," states a tribal elder, emphasizing their connection to the ancient Pueblo heritage.

-

The Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas: Nestled in the Big Thicket region of East Texas, the Alabama-Coushatta have a history of peaceful coexistence and remarkable adaptation. Migrating from what is now Alabama and Georgia in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, they settled in East Texas, maintaining neutrality during the Texas Revolution and earning the respect of figures like Sam Houston. Unlike most other tribes, they were never forcibly removed from Texas. Instead, the state of Texas set aside land for them in 1854, making them the state’s first Indian reservation. They operated under state jurisdiction for decades before achieving federal recognition in 1987. Their reservation, located near Livingston, is a vibrant community focused on cultural preservation, economic development, and environmental stewardship.

-

The Kickapoo Traditional Tribe of Texas: Perhaps the most unique story belongs to the Kickapoo. Originating in the Great Lakes region, a band of Kickapoo moved south in the 19th century, eventually establishing a dual existence across the U.S.-Mexico border near Eagle Pass. For generations, they maintained their traditional ways, often living outside mainstream society and resisting assimilation. Their remote location and ability to move freely across the border allowed them to preserve much of their language (an Algonquian dialect) and ceremonies. They were the last of the three tribes to gain federal recognition in 1983, largely due to their unique transnational status. Today, the Kickapoo Traditional Tribe of Texas operates a successful casino and other enterprises, using these ventures to fund tribal services and cultural programs.

Beyond Recognition: The Ongoing Journey

While the stories of the Tigua, Alabama-Coushatta, and Kickapoo are triumphs of survival, they represent only a fraction of the indigenous legacy in Texas. Many descendants of other historical Texas tribes, like the Lipan Apache, Tonkawa, and Comanche, continue to live in the state, working tirelessly to reclaim their heritage, revitalize languages, and educate the public about their ancestors’ contributions and struggles. They face ongoing challenges related to cultural preservation, land rights, and the fight against historical erasure.

The legacy of Native American tribes in Texas is not confined to history books. It lives in the names of rivers (Sabine, Nueces, Wichita), cities (Nacogdoches, Comanche, Waco), and the very land itself. It resonates in the enduring spirit of the three federally recognized tribes and in the ongoing efforts of unrecognized groups to assert their identity and rights.

Understanding this deep history is crucial for a complete picture of Texas. It reminds us that the state was not an empty frontier, but a homeland, a battleground, and ultimately, a place where indigenous cultures, despite immense pressures, continue to echo on the plains, reminding us of their enduring presence and profound contributions to the rich tapestry of Texas. Their journey from ancient dominion to near disappearance and finally to a powerful resurgence serves as a testament to the indomitable human spirit and the unbreakable bond between people and their ancestral lands.