New Netherland: America’s Forgotten Genesis of Diversity and Commerce

When the story of America’s colonial past is told, the narratives of Jamestown’s struggle for survival and Plymouth’s quest for religious freedom often take center stage. Yet, tucked away between these foundational myths lies a lesser-known but equally, if not more, influential chapter: New Netherland. A vibrant, chaotic, and remarkably diverse Dutch outpost, New Netherland – and its crown jewel, New Amsterdam – was not founded on piety or agricultural promise, but on the raw, unadulterated pursuit of profit. It was a commercial crucible, a pragmatic melting pot, and a precursor to the modern American metropolis, laying an indelible foundation for what would become the United States’ most iconic city: New York.

The tale begins not with a pilgrim’s prayer, but with a navigator’s quest for a shortcut to Asia. In 1609, the English explorer Henry Hudson, in the employ of the Dutch East India Company, sailed his ship, the Half Moon, into the magnificent estuary that now bears his name. While he didn’t find the Northwest Passage, he discovered something equally valuable: a vast wilderness teeming with beavers, whose pelts were highly prized in Europe for hat-making. This discovery ignited the imagination of Dutch merchants, leading to the establishment of trading posts and, by 1624, the formal colonization of New Netherland by the Dutch West India Company (DWIC).

Unlike its English counterparts, the DWIC was not primarily interested in creating a settled agrarian society or a haven for a specific religious sect. Its sole focus was the bottom line. This commercial imperative profoundly shaped the colony’s character. To maximize profits from the lucrative fur trade, the DWIC needed people, any people, to populate its outposts and process its goods. This open-door policy, radical for its time, meant that New Netherland quickly became a haven for a dizzying array of nationalities and faiths.

"No matter whether you are a German, a Frenchman, a Swede, a Pole, an Englishman, a Jew, or an Italian," declared one contemporary observer, "you are welcome as long as you can contribute to the prosperity of the colony." By the mid-17th century, the small settlement of New Amsterdam, perched on the southern tip of Manhattan Island, was a babel of languages. It was famously reported by Jesuit missionary Isaac Jogues in 1643 that eighteen different languages were spoken among the 400 or 500 inhabitants. This wasn’t merely tolerance; it was an economic necessity, a pragmatic embrace of diversity that would define the future metropolis.

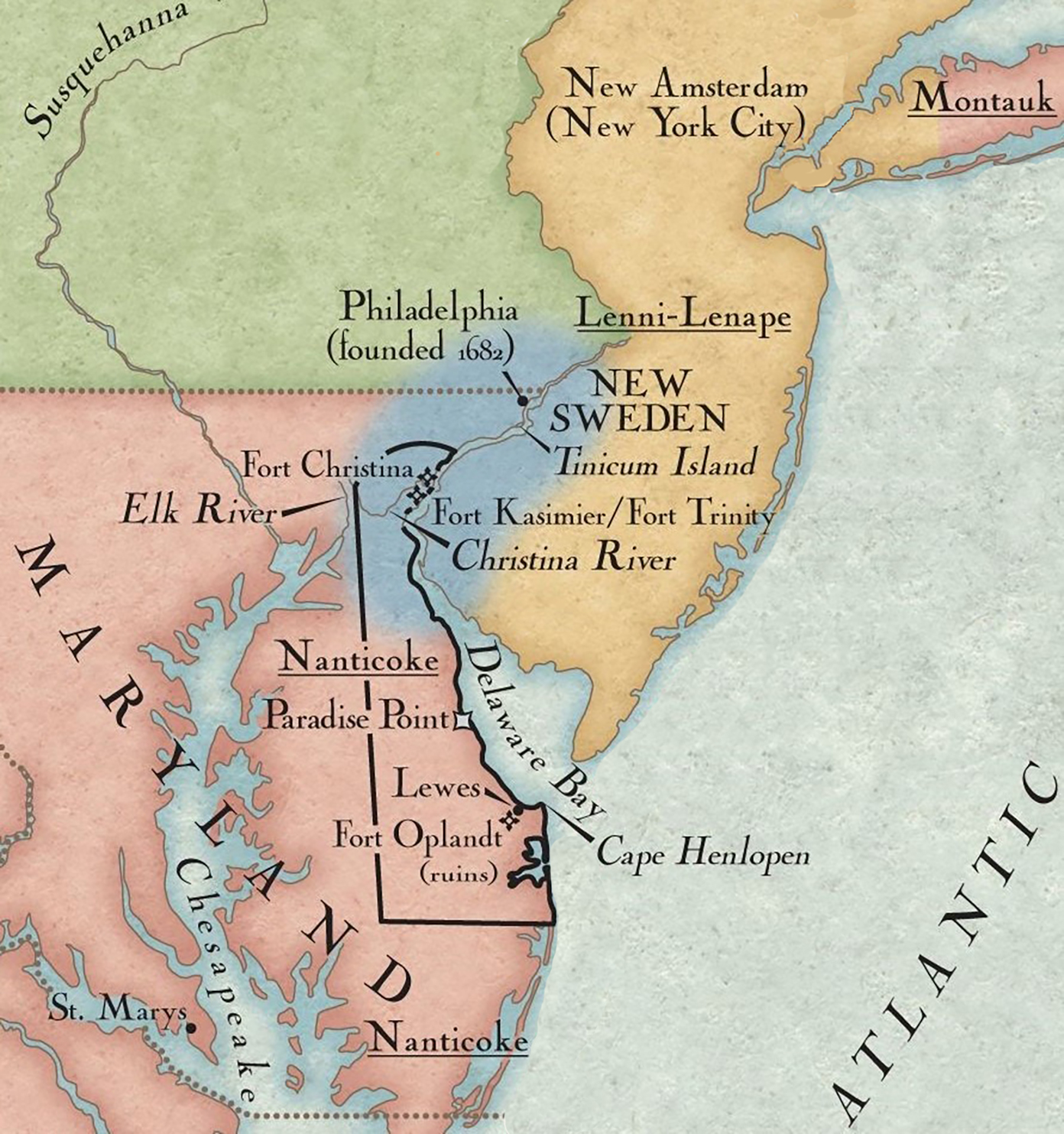

The colony’s polyglot population included not only Dutch and Walloons (French-speaking Protestants from the southern Netherlands), but also Scandinavians, Germans, English Puritans fleeing persecution in New England, and even the first Jewish refugees to arrive in North America in 1654. This mosaic of cultures, religions, and backgrounds fostered a dynamic, if sometimes contentious, society where individuals were judged less by their lineage or creed and more by their industry and ability to contribute to the colony’s commercial success.

However, New Netherland’s embrace of diversity had its dark underbelly. The DWIC, a major player in the transatlantic slave trade, brought the first enslaved Africans to the colony in 1626, just two years after its formal founding. These enslaved people, initially instrumental in building the infrastructure of New Amsterdam – clearing land, constructing roads, and building the famous wall that would give Wall Street its name – formed a significant and often brutalized segment of the population. While some were granted "half-freedom" (allowing them to work for wages after paying a tribute, but still tying their children to slavery), the institution of slavery was deeply ingrained in the colony’s economic fabric, a stark reminder that the pursuit of profit often came at a terrible human cost.

Life in New Netherland was far from idyllic. The DWIC’s primary allegiance was to its shareholders, not its settlers, leading to a largely absentee and often inept administration. The vast distances, harsh winters, and constant threat of conflict with various Native American tribes, whose lands the Dutch increasingly encroached upon, made for a challenging existence. The most devastating of these conflicts was Kieft’s War (1643-1645), ignited by the impulsive and brutal actions of Director-General Willem Kieft, who ordered the massacre of Wappinger refugees sheltering near Pavonia. This act of barbarism provoked a widespread uprising, nearly annihilating the colony and demonstrating the precariousness of Dutch claims.

It was into this volatile mix that Peter Stuyvesant, the most iconic figure of New Netherland, arrived in 1647. A one-legged, iron-willed veteran of military campaigns, Stuyvesant was sent by the DWIC to restore order and profitability to the struggling colony. He was, by all accounts, an autocrat with a penchant for strict rules and a deep-seated intolerance for anything that deviated from his Calvinist vision. He banned taverns from operating during church services, cracked down on smuggling, and attempted to suppress religious dissent, famously trying to expel the first Jewish settlers and later persecuting Quakers.

Yet, even Stuyvesant, for all his authoritarianism, was ultimately pragmatic. Overruled by the DWIC, which recognized the economic value of diverse populations, he grudgingly allowed the Jewish community to remain, albeit with restrictions. Under his stern hand, New Amsterdam blossomed. He fortified the city, established a rudimentary police force, and oversaw the construction of schools and hospitals. The colony expanded, its fur trade thrived, and its agricultural output increased. Stuyvesant’s legacy is a complex one: a dictatorial figure who, paradoxically, presided over a period of significant growth and consolidation, inadvertently reinforcing the colony’s diverse character through his company’s directives.

The end for New Netherland came not with a bang, but a strategic whimper. By the 1660s, the English, increasingly resentful of the Dutch presence that bisected their American colonies and controlled vital trade routes, decided to act. In 1664, a formidable English fleet, under the command of Colonel Richard Nicolls, sailed into New Amsterdam’s harbor and demanded its surrender. Stuyvesant, ever the stubborn soldier, initially vowed to fight, but without adequate fortifications, resources, or the support of his own citizens – many of whom saw little to gain from resisting a stronger power – he was ultimately compelled to surrender. The terms were remarkably lenient: Dutch residents were allowed to keep their property, practice their religion, and maintain their customs. New Netherland became New York, named in honor of the Duke of York, the future King James II.

Despite its relatively brief existence (just 40 years from formal colonization to English takeover), New Netherland’s impact reverberated for centuries. The English takeover, rather than erasing the Dutch influence, largely absorbed it. The pragmatic, commercial spirit of New Amsterdam lived on, defining the very character of New York City. The city’s grid plan, its real estate-driven economy, and its inherent embrace of global commerce all have roots in its Dutch origins.

The legacy is visible everywhere, if one knows where to look. "Wall Street" is a direct reference to the defensive palisade built by the Dutch to protect against English and Native American incursions. "Broadway" derives from "Breede Wegh," the widest thoroughfare in New Amsterdam. "Brooklyn" comes from Breukelen, "Harlem" from Haarlem, and "the Bowery" from Bouwerie, meaning farm. Even common American words like "stoop" (stoep), "cookie" (koekje), "boss" (baas), and "cruller" (kruller) are Dutch linguistic gifts. And perhaps most endearingly, the image of Santa Claus, or "Sinterklaas," was brought to America by Dutch settlers.

But beyond the linguistic and architectural relics, New Netherland left a more profound legacy: the blueprint for a truly diverse and commercially driven society. It demonstrated that people of different backgrounds could coexist, not necessarily out of altruism, but out of a shared economic interest. This practical pluralism, born of the demands of trade, foreshadowed the multicultural tapestry that America would become.

New Netherland may have been a commercial venture, often chaotic and imperfect, but it was also an experiment in urban living, a crucible where different cultures and ambitions collided and fused. Its story reminds us that the American ideal of a "melting pot" wasn’t born solely of idealistic dreams, but also from the rough-and-tumble realities of commerce. It was a place where fortunes were made, freedoms were tested, and the very idea of a global city took root. In a nation often defined by its grand narratives, New Netherland stands as a vital, if often overlooked, testament to the enduring power of diversity and the relentless pursuit of opportunity, forever shaping the soul of America’s greatest city.