Echoes of the Homeland: The Enduring Cultural Tapestry of the Nez Perce

In the vast, verdant landscapes where the Clearwater, Snake, and Salmon Rivers converge, a people known as the Nimiipuu, or "The People," have thrived for millennia. More commonly recognized as the Nez Perce, their name, meaning "pierced nose" in French, was an erroneous descriptor given by early European explorers, though some members of the tribe did practice nose piercing. Far more fitting is their own designation, Nimiipuu, which speaks to their deep, inherent connection to the land they call home – a connection that forms the very bedrock of their rich and resilient culture.

To understand the Nez Perce is to embark on a journey through a cultural tapestry woven with threads of profound spirituality, innovative adaptation, and an unwavering bond with the natural world. From their sophisticated subsistence strategies to their unique horse culture, their intricate artistry, and their enduring oral traditions, the Nimiipuu narrative is one of survival, wisdom, and an unyielding spirit that continues to flourish despite centuries of profound challenges.

The Land as the First Teacher: Seasonal Rounds and Subsistence

For the Nimiipuu, the land was not merely territory; it was a living entity, a generous provider, and the primary source of their identity and wisdom. Their traditional way of life was dictated by the rhythm of the seasons, a carefully orchestrated "seasonal round" that moved them across their ancestral lands in what is now parts of Idaho, Oregon, and Washington. This nomadic or semi-nomadic existence was not aimless wandering but a strategic and sustainable method of harvesting the diverse bounty of the Plateau region.

Central to their diet and culture were two pillars: salmon and camas. The annual salmon runs, particularly of Chinook and sockeye, were celebrated with reverence and meticulous preparation. Nimiipuu fishers, employing sophisticated weirs, traps, and spears, would harvest vast quantities of fish. The salmon was not just food; it was a sacred gift, a life-giver. The First Salmon Ceremony, a ritual of profound respect and gratitude, marked the beginning of the fishing season. This ceremony ensured the fish would return each year, reminding the people of their interconnectedness with all living things. As contemporary Nez Perce elder Frank B. Halfmoon once stated, "The salmon is our brother. It comes up the river to feed us, and we must honor it." The dried salmon, processed and stored, provided vital protein through the long winter months.

Equally significant was the camas root (Camassia quamash), a starchy, onion-like bulb that grew in vast meadows, transforming them into a sea of purple blossoms in spring. The gathering of camas was primarily the work of women, who used specially designed digging sticks. This was a communal activity, fostering social bonds and shared knowledge. The bulbs were then slow-roasted in earthen ovens for days, a process that converted complex carbohydrates into digestible sugars, making them sweet and nutritious. Like salmon, camas was dried and stored, forming another crucial winter staple. The Nez Perce managed these camas meadows meticulously, often burning off old growth to encourage new, healthier crops, demonstrating an early understanding of sustainable land management.

Beyond salmon and camas, the Nimiipuu diet was incredibly diverse, including deer, elk, bear, various birds, berries (huckleberries, serviceberries), and other roots. Hunting was a communal activity, requiring skill, patience, and a deep knowledge of animal behavior. Every part of the animal was utilized – meat for food, hides for clothing and shelter, bones and antlers for tools, and sinew for thread.

The Horse Culture: A Revolution on Four Legs

The arrival of the horse in the early 18th century profoundly transformed Nez Perce culture, elevating them to a position of prominence among Plateau tribes. The Nimiipuu quickly became master horse breeders, developing the distinctive Appaloosa, famed for its spotted coat, intelligence, and endurance. This was not merely the acquisition of an animal; it was a revolution in their way of life.

Horses facilitated more extensive hunting expeditions, allowing the Nez Perce to travel to the Great Plains to hunt buffalo, expanding their food sources and trade networks. They became expert riders, their horsemanship a source of immense pride and strategic advantage. Horses also became a measure of wealth and status, influencing social structures and inter-tribal relations. The Appaloosa, in particular, became an extension of the Nimiipuu spirit, a symbol of their freedom and mastery over their environment. "Without our horses," it was often said, "we would not be the Nimiipuu." The Appaloosa, today recognized globally, stands as a living testament to Nez Perce ingenuity and their deep bond with these majestic animals.

Spiritual Worldview: Harmony with the Cosmos

The Nimiipuu spiritual worldview is deeply animistic, rooted in the belief that all living things – animals, plants, rivers, mountains – possess a spirit and are interconnected. The Creator, often referred to as Wéeyet (or a similar concept), is the ultimate source of all life and power. This power, or wéyekin, could be sought through vision quests, typically undertaken by young people in solitude in sacred places. During these quests, individuals would seek guidance and a guardian spirit, often an animal, that would offer protection, wisdom, and special abilities throughout their lives. Dreams were also considered vital conduits for spiritual messages and insights.

Storytelling was a cornerstone of their spiritual and educational practices. Elders, revered for their wisdom and knowledge, passed down oral histories, myths, legends, and moral teachings through intricate narratives. These stories explained the origins of the world, the behavior of animals, the proper way to live, and the history of the Nimiipuu people. They were not merely entertainment but vital cultural instruction, reinforcing values like generosity, humility, courage, and respect for all creation. The Coyote stories, for instance, often played the role of a trickster figure, teaching lessons through his follies.

Ceremonies and rituals, such as the First Foods Feasts (celebrating the first salmon, camas, and berries), reinforced their spiritual connection to the land and its bounty. These were moments of communal gathering, gratitude, and reaffirmation of their cultural identity.

Social Fabric and Governance: Consensus and Community

Nez Perce society was largely egalitarian, emphasizing consensus, individual autonomy, and communal responsibility. Leadership was not about absolute power but about influence, wisdom, and the ability to unite the community. Chiefs, like the renowned Chief Joseph (Hinmatóowyalahtq̓it or "Thunder Rolling Down the Mountain"), were respected advisors, strategists, and spokespeople rather than rulers. Decisions were made through extensive discussion and agreement among elders and influential members of the band.

The family and the band (a localized group of families) were the primary social units. Extended families lived together, fostering a strong sense of kinship and mutual support. Children were raised communally, taught by elders, parents, and the natural world itself. Respect for elders, who held the accumulated wisdom of generations, was paramount. Generosity (wéwookiye), especially towards those in need, was a highly valued trait, reflecting the communal spirit necessary for survival and prosperity.

Art, Craft, and Expression: Beauty in Utility

Nez Perce artistry is a vibrant testament to their ingenuity and aesthetic sensibilities. Their crafts were not merely decorative but deeply functional, imbued with spiritual meaning and cultural significance.

Basketry was a highly developed art form, with two main types: twined and coiled. The twined baskets, often made from bear grass, corn husks, and other natural fibers, were incredibly durable and used for gathering, cooking (using hot rocks to boil water inside), and storage. They featured intricate geometric patterns and often incorporated natural dyes. Coiled baskets, though less common, were also made.

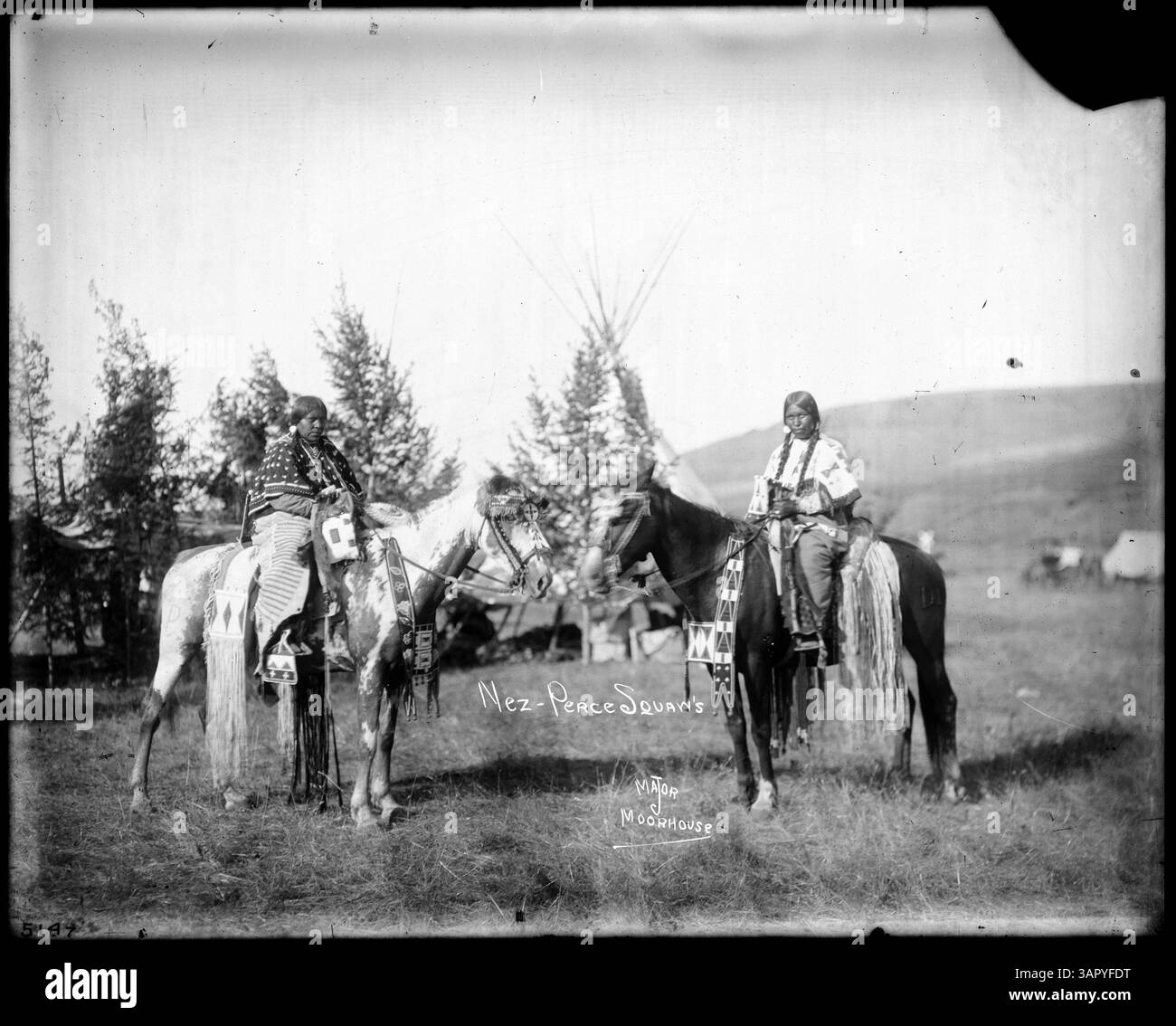

Beadwork, particularly after the introduction of glass beads through trade, became another prominent art form. Nez Perce beadwork is characterized by its meticulous detail, vibrant colors, and distinctive designs, often depicting floral motifs or abstract patterns. These beads adorned clothing (made from tanned deer and elk hides), bags, horse regalia, and ceremonial items, reflecting both individual artistic expression and communal identity.

Clothing, typically made from finely tanned buckskin, was often adorned with fringes, porcupine quills, shells, and beads. Functionality was key, but beauty was never sacrificed. Music, expressed through drumming, singing, and flutes, also played a vital role in ceremonies, social gatherings, and personal expression.

Resilience and Modernity: The Enduring Spirit

The tragic events of the 1877 Nez Perce War, a desperate attempt to avoid forced removal from their ancestral lands, marked a devastating chapter in their history. Chief Joseph’s famous surrender speech, "From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever," echoed the profound loss but also the enduring spirit of his people. The subsequent forced relocation and the erosion of traditional ways tested the Nimiipuu to their core.

Yet, despite immense pressures, the Nez Perce people have demonstrated remarkable resilience. Today, the Nez Perce Tribe is a federally recognized sovereign nation, centered on the Nez Perce Reservation in Lapwai, Idaho. They are actively engaged in revitalizing their language (Sahaptin), which is critically endangered but being taught to younger generations. Cultural education programs, traditional arts workshops, and annual powwows serve to preserve and celebrate their heritage. Efforts are also underway to restore salmon populations, reclaim ancestral lands, and manage natural resources in a way that aligns with their traditional ecological knowledge.

The Nimiipuu continue to draw strength from their ancestors, their land, and their profound cultural practices. Their story is a powerful reminder that culture is not static; it is a living, breathing entity that adapts, evolves, and endures. The echoes of their ancient homeland, the wisdom of their elders, and the spirit of the Appaloosa still resonate deeply within the Nez Perce people, guiding them as they navigate the complexities of the modern world while holding fast to the rich tapestry of their identity. They stand as a testament to the enduring power of culture, a beacon of resilience, and a living bridge between a profound past and a promising future.