The Epic Flight: Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce’s Desperate Bid for Freedom

By [Your Name/Journalist Alias]

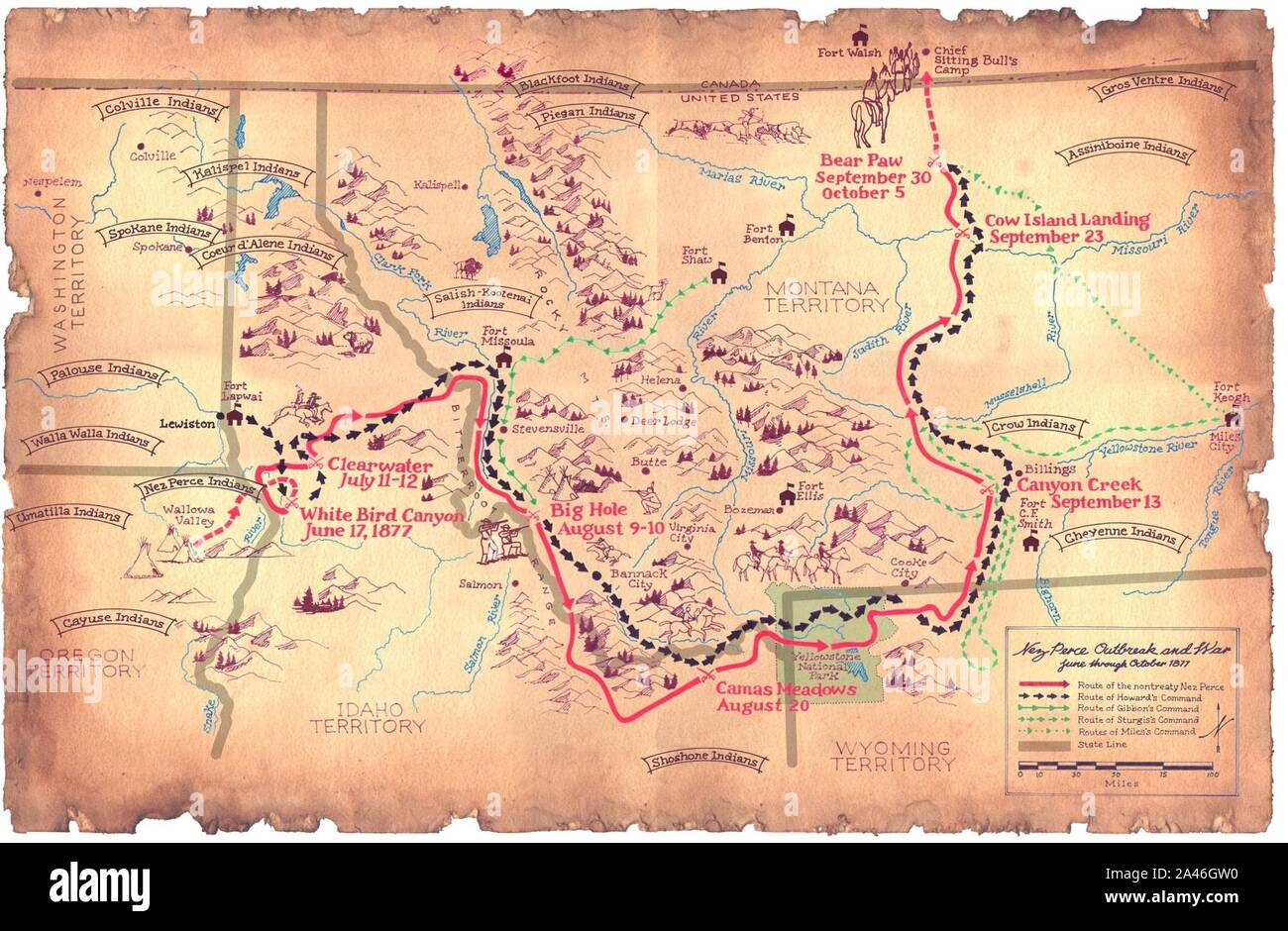

In the annals of American history, few sagas resonate with such profound tragedy, courage, and desperate resolve as the Nez Perce Flight of 1877. For 117 days, a small band of fewer than 800 Nimiipuu (as the Nez Perce call themselves), including women, children, and elders, outmaneuvered and outfought a U.S. Army more than 2,000 strong, traversing over 1,170 miles of rugged, unforgiving terrain across four states. Their odyssey, a desperate bid to preserve their way of life and escape forced relocation, stands as a testament to human endurance and a searing indictment of manifest destiny.

At its heart, the conflict was born of broken promises and unbridled expansion. For centuries, the Nez Perce had inhabited the fertile Wallowa Valley in northeastern Oregon, a land rich in game and sacred to their ancestors. The Treaty of 1855 had guaranteed them a vast reservation, but the discovery of gold in Idaho in the early 1860s shattered this peace. A subsequent "Thief Treaty" in 1863, signed by a minority of chiefs without the consent of the majority, drastically reduced their lands, ceding millions of acres, including the cherished Wallowa Valley, to the U.S. government.

The "non-treaty" Nez Perce, led by figures like Chief Joseph (Hinmatóowyalahtq̓it, or "Thunder Rolling Down the Mountain"), Chief Looking Glass, White Bird, Ollokot (Joseph’s brother), and Too-hul-hul-sote, steadfastly refused to recognize the fraudulent treaty. Joseph, known for his wisdom and eloquence, famously stated, "The earth is my mother. I will not sell the earth." For years, they resisted pressures to move, their peaceful defiance a thorn in the side of westward expansion.

The Ultimatum and the Inevitable Spark

The precarious peace shattered in the spring of 1877. General Oliver O. Howard, known as "Praying Howard" for his piety, was tasked with enforcing the removal order. He delivered an ultimatum: the Nez Perce must move to the Lapwai Reservation in Idaho within 30 days or face military force.

The decision was agonizing. The chiefs knew that resistance meant war and probable annihilation. Joseph, despite his deep love for his ancestral lands, initially advocated for peace, hoping to avoid bloodshed. "I would have given my life to stay," he later recounted. But as they gathered to move, a series of tragic events ignited the conflict. Hot-headed young warriors, fueled by grief and anger over past injustices—including the murder of a Nez Perce man and the theft of their horses—retaliated, killing several white settlers in what became known as the Salmon River Massacre.

This act, though condemned by the chiefs, sealed their fate. There was no turning back. The flight had begun.

The First Shots: White Bird Canyon

On June 17, 1877, near White Bird Canyon in Idaho, the Nez Perce encountered Captain David Perry’s U.S. cavalry. What followed was a stunning defeat for the Americans. The Nez Perce, though outnumbered, were master horsemen and intimate with the terrain. Utilizing a tactical ambush and superior marksmanship, they routed Perry’s troops, killing 34 soldiers without a single Nez Perce fatality.

The victory at White Bird Canyon, while boosting Nez Perce morale, also confirmed the U.S. Army’s resolve. General Howard, humiliated, began a relentless pursuit, determined to bring the "renegades" to justice.

The Battle of the Clearwater and the Strategic Shift

As Howard’s forces closed in, the Nez Perce continued their retreat, seeking safety. On July 11-12, they clashed again with Howard’s command at the Battle of the Clearwater. This time, the outcome was different. After a fierce, two-day engagement, the Nez Perce, facing superior firepower and numbers, were forced to withdraw, leaving behind their camp and many vital supplies. While not a decisive defeat, it signaled that holding ground against the army was no longer an option.

It was after Clearwater that the Nez Perce made a fateful decision: they would not head to Lapwai. Instead, they would embark on an audacious journey across the Bitterroot Mountains, aiming for Montana, hoping to find refuge with the Crow people, or failing that, to cross into Canada, the "Grandmother’s Country," where they believed they would be safe from U.S. pursuit. This marked the true beginning of their epic flight.

Through the Bitterroots: Lolo Pass and Beyond

The trek over the treacherous Lolo Pass was a monumental feat. The Nez Perce, with their women, children, and elderly, navigated dense forests, steep slopes, and swift rivers, carrying their entire lives with them. Their incredible mobility and knowledge of the land often left the heavily supplied U.S. Army trailing behind. At the eastern end of Lolo Pass, Montana volunteers attempted to block their passage at a makeshift fortification dubbed "Fort Fizzle." The Nez Perce simply bypassed it, negotiating with the locals and moving on, largely unmolested.

General Howard, meanwhile, was falling further behind. His men were exhausted, and his supply lines stretched thin. The Nez Perce, though suffering from the rigors of the journey, maintained their discipline and spirit. Their hope was that once in Montana, they might be left alone. This hope was tragically misplaced.

The Horror of Big Hole

On August 9, disaster struck. While camped in the Big Hole Valley, believing themselves safe, the Nez Perce were ambushed at dawn by Colonel John Gibbon’s command. The attack was devastating. Soldiers poured into the sleeping camp, firing indiscriminately into lodges. Scores of Nez Perce, particularly women and children, were killed in the initial onslaught.

"It was a terrible sight," remembered Yellow Wolf, a Nez Perce warrior. "Women and children screaming, trying to escape… Soldiers shooting them down like buffalo."

But the Nez Perce, despite the horror, rallied. Warriors, led by Chief Ollokot, fought back with incredible ferocity, turning the tide. They pinned Gibbon’s forces down, inflicting heavy casualties, including Gibbon himself, who was wounded. After a day of brutal fighting, the Nez Perce were forced to abandon their camp, but they had managed to escape, carrying their wounded and burying their dead. The Battle of the Big Hole was a Pyrrhic victory for the U.S. Army and a profound psychological blow for the Nez Perce, who lost a significant portion of their people, including their vital elderly leaders.

The Race to Canada: Yellowstone and Miles’s Pursuit

From Big Hole, the Nez Perce pressed eastward, their resolve hardened by loss. They traversed the newly established Yellowstone National Park, encountering and briefly interacting with bewildered tourists. Their pace was relentless, driven by the desperate hope of reaching the Canadian border, now only a few hundred miles away.

General Howard continued his pursuit, but another formidable force was now on their trail: Colonel Nelson Miles, commanding the Fifth Infantry from Fort Keogh in Montana. Miles, leading fresh troops and a detachment of Cheyenne scouts, aimed to cut off the Nez Perce before they could reach safety. On September 13, at Canyon Creek, Miles’s forces briefly engaged the Nez Perce, who again skillfully evaded a full-scale battle, losing many of their precious horses but escaping the trap.

The Nez Perce were now a mere 40 miles from the Canadian border. Exhausted, battered, and low on supplies, they finally paused to rest in the Bear Paw Mountains, believing they had outrun their pursuers.

The Final Stand: Bear Paw Mountains

On September 30, 1877, as snow began to fall, Miles’s cavalry launched a surprise attack on the Nez Perce camp in the Bear Paw Mountains. The attack was fierce, but the Nez Perce quickly dug in, creating defensive positions that allowed them to withstand the initial assault. A brutal siege ensued, lasting five days.

The conditions were horrific. The Nez Perce, freezing and starving, fought bravely. Many warriors, including Chief Ollokot, were killed. The toll on the women and children was immense. With each passing day, hope dwindled. The Canadian border was agonizingly close, but they could not break through Miles’s lines.

General Howard, having finally caught up, arrived on October 4. The combined U.S. forces made the situation untenable. With his people suffering, his brother dead, and no hope of escape, Chief Joseph made the most difficult decision of his life.

"I Will Fight No More Forever"

On October 5, 1877, Chief Joseph rode out to surrender to General Miles and General Howard. His words, delivered through an interpreter, have echoed through history, becoming one of the most poignant speeches of the American West:

"Tell General Howard I know his heart. What he told me before, I have in my heart. I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed. Looking Glass is dead. Too-hul-hul-sote is dead. The old men are all dead. It is the young men now who say yes or no. He who led the young men is dead. It is cold, and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food; no one knows where they are – perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children, and see how many of them I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs! I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever."

A Legacy of Broken Promises and Enduring Spirit

Joseph’s surrender was conditional: his people would be allowed to return to their homeland. But this promise, like so many before it, was broken. The Nez Perce were first exiled to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, then to a malarial reservation in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). Many perished from disease and despair in the unfamiliar climate.

Despite constant appeals and advocacy from Chief Joseph, who became a reluctant celebrity and powerful voice for his people, the majority of the Nez Perce never returned to the Wallowa Valley. Joseph himself was eventually allowed to move to the Colville Reservation in Washington State in 1885, but his heart remained in Wallowa. He died there in 1904, a prisoner of war to the end, never having seen his ancestral home again.

The Nez Perce Flight of 1877 remains a powerful and tragic chapter in American history. It highlights the brutal realities of westward expansion, the resilience of indigenous peoples, and the profound moral cost of broken treaties. Chief Joseph, a brilliant strategist and compassionate leader, became an enduring symbol of resistance against overwhelming odds, his words a haunting reminder of a desperate people’s courage in the face of insurmountable loss. Their journey, though ending in surrender, stands as an epic testament to their indomitable spirit and their unyielding love for their land and freedom.