The Enduring Canvas: Unraveling the Rich Tapestry of Nez Perce Traditional Arts

From the sweeping plains and towering mountains that once defined their ancestral lands, the Nimiipuu, or Nez Perce people, wove a vibrant and profound artistic tradition that speaks volumes about their history, resilience, and spiritual connection to the world around them. Far more than mere decoration, Nez Perce traditional arts are living documents, intricate narratives etched into hide, beaded onto cloth, and woven into fiber, each piece a testament to ingenuity, cultural identity, and an enduring spirit that has weathered centuries of change. To truly appreciate this artistic legacy is to understand the soul of a people deeply intertwined with their environment and heritage.

The Nez Perce, whose traditional territory spanned parts of present-day Idaho, Oregon, Washington, and Montana, were renowned for their sophisticated horse culture, their intricate knowledge of the land, and their complex social structures. This rich cultural backdrop provided the canvas for an artistic expression that was both deeply practical and profoundly spiritual. Every object, from a child’s cradleboard to a warrior’s shield, was imbued with purpose and beauty, reflecting a worldview where utility and aesthetics were inseparable.

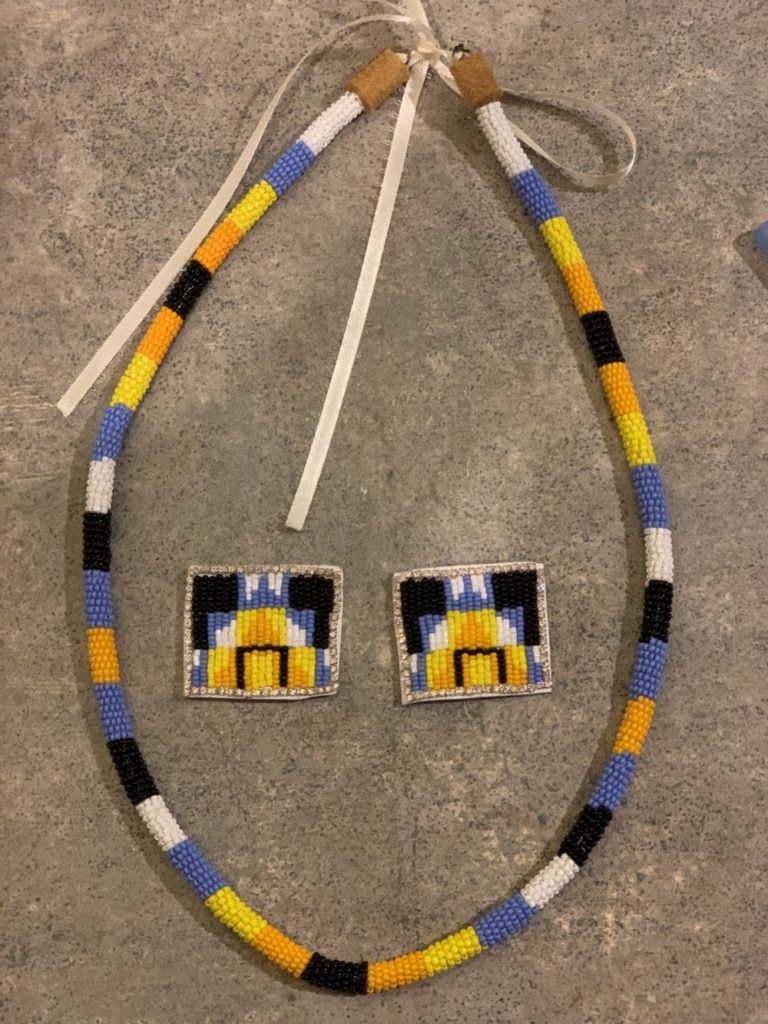

One of the most distinctive and widely recognized aspects of Nez Perce traditional art is their beadwork. Before the arrival of European traders, Nez Perce artists utilized natural materials like porcupine quills, shells, seeds, and elk teeth to adorn clothing and utilitarian objects. The painstaking process of quillwork involved softening, flattening, and dyeing porcupine quills, then sewing them onto hide or fabric using a variety of stitches to create geometric patterns. With the introduction of glass beads through trade networks in the 18th and 19th centuries, Nez Perce artists quickly adopted this new medium, transforming their designs and expanding their palette.

Nez Perce beadwork is characterized by its meticulous detail, vibrant color combinations, and often asymmetrical yet balanced designs. Unlike some other Plains tribes, Nez Perce beadwork frequently incorporates open spaces, allowing the hide or fabric background to show through, creating a unique visual texture. Common motifs include geometric shapes like triangles, diamonds, and stepped patterns, often interpreted as mountains, rivers, and natural elements, reflecting their deep connection to the landscape. Floral designs, sometimes influenced by European floral patterns but rendered with a distinctive Nez Perce flair, also became prominent.

A contemporary Nez Perce artist, speaking on the continuity of tradition, might say, "When I pick up my needles and beads, I feel the hands of my grandmothers guiding me. Every stitch connects me to them, to our land, and to the stories embedded in these patterns. It’s more than just art; it’s a prayer, a history lesson, and a way to ensure our culture thrives." This sentiment captures the essence of how traditional arts remain a vital link to the past while actively shaping the present and future.

Beyond beadwork, clothing and regalia were central to Nez Perce artistic expression. Moccasins, for instance, were not merely footwear but elaborate canvases. Made from tanned deer or elk hide, they often featured intricate beadwork on the vamp and cuffs, sometimes incorporating fringe, quills, or even human hair. Dresses for women and shirts for men were adorned with dentalium shells (a highly valued trade item), elk teeth, and extensive beadwork, signifying status, wealth, and tribal identity. A chief’s shirt, for example, might be heavily fringed and decorated with elaborate beadwork, reflecting his standing within the community.

Another hallmark of Nez Perce artistry is their unique cornhusk bags (also known as Nez Perce bags or "sally bags"). Unlike baskets woven from rigid materials, these bags are pliable and lightweight, made from twined and false-embroidered strands of twisted dogbane, hemp, or other plant fibers, overlaid with brightly dyed cornhusks. These bags were essential for gathering roots, berries, and other plant foods, and for storing personal items. Their distinctive geometric patterns, often in shades of red, black, yellow, and blue, are immediately recognizable.

The creation of a cornhusk bag is a labor-intensive process that speaks to the patience and skill of Nez Perce women. The fibers are carefully prepared, often twisted by hand, and then twined to form the base structure. The dyed cornhusks are then intricately woven in, creating patterns that are both aesthetically pleasing and structurally reinforcing. These bags served practical purposes, but their beauty elevated them to works of art, often traded and highly prized by neighboring tribes. The enduring quality of these bags, many of which survive in museum collections today, is a testament to the mastery of the weavers.

Parfleche, rawhide containers used for storing and transporting dried foods, clothing, and ceremonial items, represent another significant artistic medium. Made from stiff, untanned hide, parfleche were folded and often painted with bold, geometric designs using natural pigments derived from minerals and plants. These abstract patterns, often featuring lines, squares, and circles, were not merely decorative; they held symbolic meaning, sometimes representing elements of the natural world, spiritual concepts, or tribal stories. The portability and durability of parfleche made them ideal for the nomadic lifestyle of the Nez Perce, particularly after the widespread adoption of the horse, which allowed for greater mobility and the transport of more possessions.

The horse, in fact, became an integral part of Nez Perce culture and, consequently, their art. The Nez Perce were master horse breeders and riders, developing the Appaloosa breed, famous for its spotted coat. Horse regalia – saddles, bridles, cruppers, and blankets – became elaborate canvases for artistic expression, adorned with intricate beadwork, porcupine quills, and painted designs. A Nez Perce horse, fully arrayed in its ceremonial gear, was a breathtaking sight, a testament to the bond between rider and animal, and a powerful symbol of status and wealth.

Beyond these prominent forms, Nez Perce artists also excelled in wood carving (pipes, bowls, effigies), stone carving, and the creation of ceremonial objects like rattles and drums. Even everyday tools and weapons, such as bows, arrows, and shields, were often decorated, reflecting the belief that infusing an object with beauty also imbued it with power and respect. For the Nez Perce, art was not confined to a gallery or museum; it was woven into the fabric of daily life, into every significant moment and every cherished possession.

The spirituality and symbolism inherent in Nez Perce art are profound. Designs were often inspired by dreams, visions, and the natural world, serving as a visual language that communicated stories, spiritual beliefs, and tribal identity. Animals like the eagle, bear, and salmon held significant spiritual meaning and sometimes found their way into artistic representation. The act of creation itself was often a spiritual endeavor, a way for the artist to connect with their ancestors, the land, and the Great Spirit. "Our art is our voice," an elder might share, "it speaks of where we come from, what we believe, and where we are going. It’s a way to keep our history alive in our hands."

However, the rich artistic tradition of the Nez Perce faced immense challenges with the arrival of Euro-American settlers and the subsequent policies of forced assimilation. The devastating Nez Perce War of 1877 and the forced removal of many bands to reservations severely disrupted traditional ways of life, impacting the transmission of artistic knowledge. Access to traditional materials became limited, and the pressure to adopt Euro-American customs led to a decline in the practice of many traditional arts.

Yet, the artistic spirit of the Nez Perce proved resilient. Despite immense hardship, master artists continued to create, often adapting to new materials and market demands while retaining the essence of their cultural aesthetic. The late 20th and early 21st centuries have witnessed a powerful revival of Nez Perce traditional arts. Cultural centers, tribal schools, and dedicated artists are actively working to reclaim, preserve, and pass on these invaluable skills to new generations. Workshops teach traditional tanning, beading, twining, and quillwork techniques, ensuring that the intricate knowledge accumulated over centuries is not lost.

Contemporary Nez Perce artists are not merely replicating old forms; they are innovating, blending traditional techniques and motifs with modern interpretations, creating new expressions that resonate with today’s world while honoring their heritage. This dynamic interplay between tradition and innovation ensures that Nez Perce art remains a living, evolving entity. It can be seen in the vibrant regalia at powwows, in museum exhibits showcasing both historical and contemporary pieces, and in the hands of young artists learning from their elders.

In conclusion, the traditional arts of the Nez Perce are a magnificent testament to a people’s enduring strength, creativity, and deep connection to their cultural identity. From the practical beauty of a cornhusk bag to the spiritual depth of a beaded design, each piece tells a story of resilience, adaptation, and a profound respect for the world. As the Nimiipuu continue to navigate the complexities of the modern era, their traditional arts serve as a vital anchor, a vibrant link to their ancestors, and a powerful statement that their culture, though challenged, remains a dynamic and beautiful force in the world. The threads of their artistic legacy continue to be woven, ensuring that the canvas of Nez Perce identity remains rich, vibrant, and eternally unfolding.