Echoes in the Wild: The Enduring Legacy of Nez Perce Traditional Hunting Grounds

The American West, often romanticized as a boundless frontier, was, for millennia, a meticulously managed homeland. Nowhere is this truth more poignantly etched than in the story of the Nez Perce (Nimiipuu) and their vast traditional hunting grounds. Far more than mere territory for sustenance, these lands – stretching from the Bitterroot Mountains to the Great Plains, encompassing the lush valleys of the Snake, Clearwater, and Salmon Rivers – were the very fabric of their identity, their spirituality, and their way of life. Today, the echoes of their ancient journeys and the tragic loss of their ancestral domains resonate as a powerful reminder of a stewardship profound and a resilience enduring.

For countless generations before the arrival of European settlers, the Nimiipuu, or "The People," thrived in a sprawling homeland that defied simple boundaries. Their territory, a mosaic of diverse ecosystems, provided an abundance of resources that shaped their semi-nomadic existence. Unlike the sedentary agricultural societies often envisioned by early Europeans, the Nez Perce embraced a sophisticated system of seasonal migration, following the rhythms of nature to harvest its bounty.

Their year was a symphony of movement. Spring would see them gathering in the lower elevations, where the first shoots of camas – a vital starchy root – emerged from the earth. The Camas Prairie in present-day Idaho was a particularly significant gathering place, not just for food but for social exchange, ceremonies, and trade. Women, with their specialized digging sticks, would harvest vast quantities of the nutritious bulbs, which were then baked in earthen ovens, providing a staple food that could be stored for months.

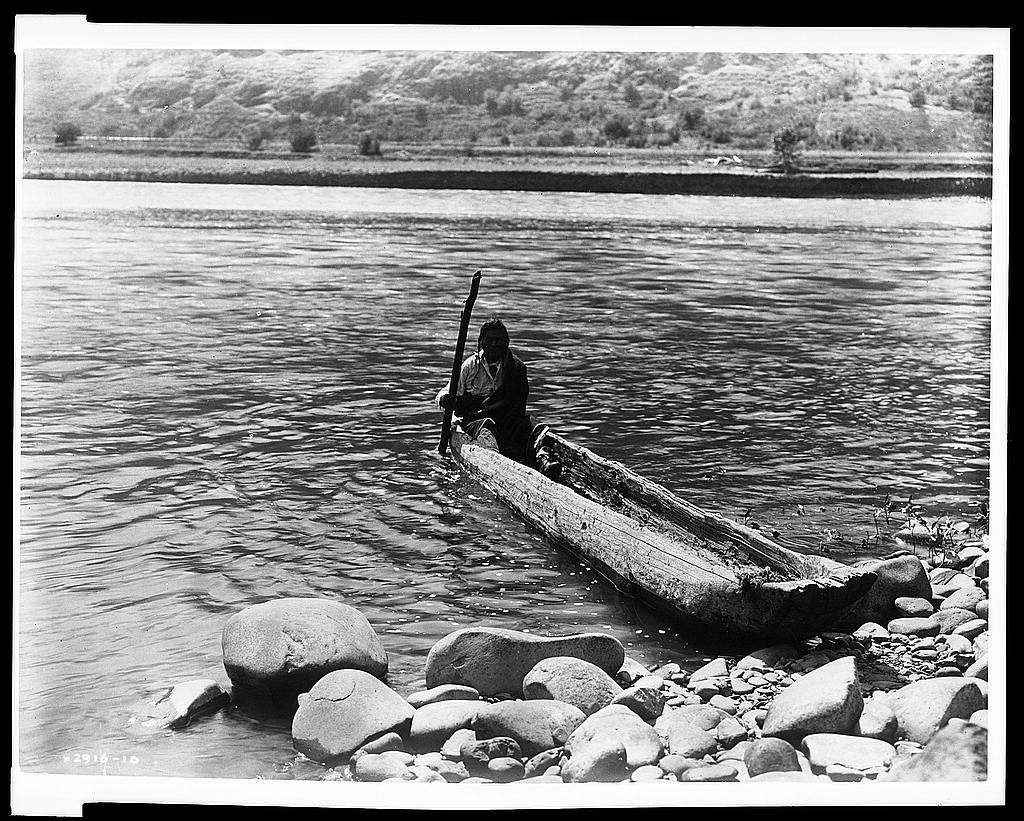

As summer matured, attention would turn to the abundant salmon runs. The Snake and Clearwater Rivers, teeming with these magnificent fish, became vital fishing grounds. Using ingenious traps, weirs, and spears, the Nez Perce would harvest enough salmon to dry and smoke, ensuring sustenance through the leaner months. This communal activity fostered deep bonds and reinforced their spiritual connection to the waterways, which they viewed as sacred arteries of life.

Late summer and early fall beckoned them eastward, across the formidable Bitterroot Mountains via ancient trails like the Lolo Trail, into the vast expanse of the Great Plains. Here, the thundering herds of buffalo awaited. The buffalo hunt was not merely a pursuit of food; it was a grand undertaking, requiring immense skill, courage, and collective organization. It provided not only meat but hides for tipis and clothing, bones for tools, and sinew for thread – every part utilized with reverence and efficiency. The hunts were dangerous, exhilarating, and deeply spiritual, reinforcing the warriors’ prowess and the community’s interdependence.

This intricate annual cycle was underpinned by a profound philosophy known as Tamánwit, or natural law. It emphasized harmony, balance, and respect for all living things. The land was not a resource to be exploited but a living entity, a mother providing for her children. "The earth is our mother," Chief Joseph famously articulated. "From her we get our food, our clothing, our shelter. She gives us our wisdom. She gives us our laws." This deep spiritual connection meant that every stream, every mountain, every grove of trees held stories, ancestral spirits, and profound meaning. Hunting grounds were thus sacred spaces, imbued with history and identity, not just economic value.

The arrival of Lewis and Clark in 1805 marked the initial contact with the Nez Perce, a meeting characterized by mutual curiosity and, importantly, aid from the Nimiipuu to the struggling American explorers. This early relationship, built on respect and hospitality, belied the seismic shifts that would soon follow. Trappers, missionaries, and eventually a flood of settlers, driven by the lure of gold and fertile lands, began to encroach upon the Nez Perce domain.

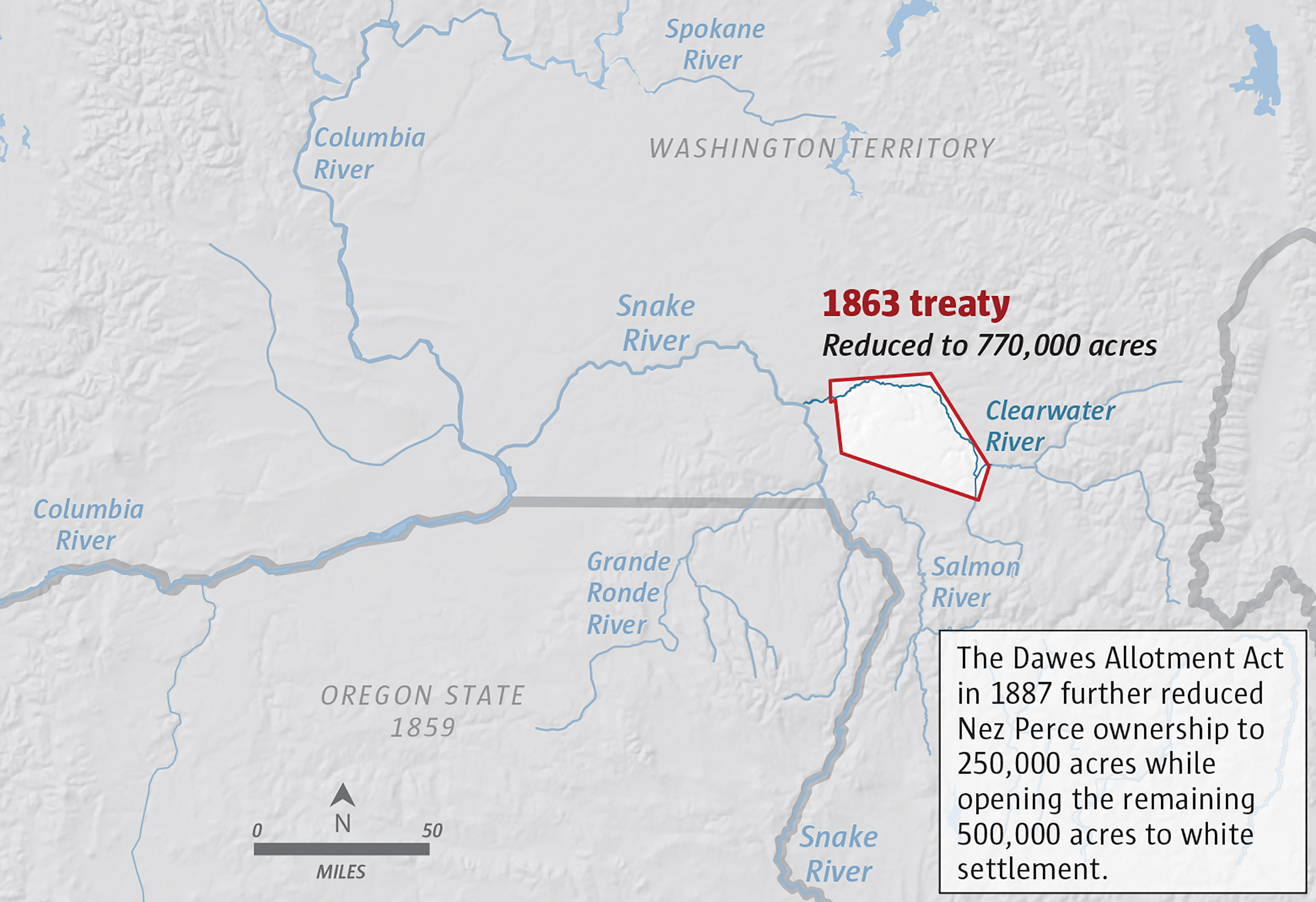

The mid-19th century brought the era of treaties, instruments of American expansion that fundamentally misunderstood and ultimately betrayed the Nimiipuu’s relationship with their land. The Treaty of 1855, while significantly reducing their ancestral territory, still recognized a vast reservation of 7.7 million acres, encompassing much of their traditional hunting and fishing grounds. For a time, it seemed a precarious peace might hold.

However, the discovery of gold in Nez Perce territory in 1860 triggered a massive influx of miners and settlers, overwhelming the fragile boundaries. The U.S. government, bowing to pressure, convened another council in 1863. The resulting "Thief Treaty," as it became known to the non-treaty Nez Perce bands, unilaterally slashed their reservation to a mere 750,000 acres – less than one-tenth of the 1855 agreement. Crucially, this new boundary excluded the Wallowa Valley in Oregon, the ancestral home of Chief Joseph’s band, and other cherished lands of bands led by Looking Glass, White Bird, and Too-hul-hul-sote.

For the Nimiipuu, the land was not a commodity to be bought and sold; it was their mother, their history, their very being. The concept of "selling" land was utterly alien. Chief Joseph eloquently stated, "Do not misunderstand me, but understand me fully with reference to my affection for the land. I never said the land was mine to do with as I chose. The one who has the right to dispose of it is the one who has created it." The non-treaty chiefs refused to sign, believing they could not surrender what was not theirs to give.

For years, Chief Joseph and his fellow leaders resisted relocation, attempting to live peacefully on their traditional lands. But the pressure mounted, culminating in an ultimatum from General O.O. Howard in 1877: move to the reservation or face military action. Faced with inevitable conflict, the non-treaty bands, totaling around 800 people (with only about 200 warriors), chose a desperate flight for freedom.

What followed was one of the most remarkable and tragic chapters in American military history: the Nez Perce War of 1877. For 117 days, the Nimiipuu, fighting for their homeland and their way of life, outmaneuvered and outfought a U.S. Army more than four times their size. They traversed over 1,170 miles across Oregon, Idaho, Wyoming, and Montana, hoping to reach Sitting Bull’s Lakota people in Canada. They fought bravely at places like White Bird Canyon, Clearwater, Big Hole, and Bear Paw.

Their journey was a testament to their intimate knowledge of the land – their ancestral hunting grounds, now a battleground. They moved with the speed and stealth of people who knew every valley, every pass, every hidden spring. Their survival relied on the very skills honed over centuries of hunting and migration. But the pursuit was relentless, and their numbers dwindled.

On October 5, 1877, just 40 miles from the Canadian border, exhausted, starving, and surrounded, Chief Joseph surrendered near the Bear Paw Mountains in Montana. His surrender speech, delivered with a broken heart, remains one of the most powerful laments in American history:

"I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed; Looking Glass is dead, Too-hul-hul-sote is dead. The old men are all dead. It is the young men now who say yes or no. He who led the young men [Ollokot] is dead. It is cold, and we have no blankets; the little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food. No one knows where they are—perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children, and see how many of them I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs! I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever."

The promise that they would be allowed to return to their homeland was broken. The surviving Nez Perce were exiled to reservations in Kansas and Oklahoma, far from their beloved mountains and rivers, suffering immense hardship and loss of life. It was not until 1885 that some, including Chief Joseph, were finally allowed to return to the Pacific Northwest, though not to their cherished Wallowa Valley. Joseph spent his remaining years in exile on the Colville Reservation in Washington, a prisoner of war until his death in 1904, still longing for his homeland.

Today, the Nez Perce Tribe, headquartered in Lapwai, Idaho, continues to uphold the legacy of their ancestors. While the vast traditional hunting grounds are now largely under federal or private ownership, the Nimiipuu maintain treaty rights to hunt, fish, and gather in ceded territories. They are active in co-management efforts with federal agencies, working to restore salmon runs, protect critical habitats, and preserve the ecological integrity of their ancestral lands. Cultural revitalization efforts ensure that the language, stories, and traditional practices connected to these lands are passed down through generations.

The story of the Nez Perce hunting grounds is more than a historical account of loss; it is a profound narrative of identity, resilience, and the enduring human connection to place. It serves as a vital reminder that for indigenous peoples, land is not merely property but a living repository of culture, spirituality, and survival. The echoes of their ancient journeys across those vast plains and through those majestic mountains continue to call, urging us to listen, to understand, and to respect the deep, sacred bond between a people and their homeland.