Ohkay Owingeh: Echoes of Eternity, Rhythms of Resilience in New Mexico’s Sacred Valley

Nestled in the fertile Española Valley of northern New Mexico, where the Rio Grande whispers ancient tales and the Sangre de Cristo Mountains stand as silent sentinels, lies Ohkay Owingeh. For centuries, this vibrant Pueblo was known by a Spanish name, San Juan Pueblo. But in a powerful act of self-determination and cultural reclamation, the community formally reverted to its ancestral Tewa name in 2005: Ohkay Owingeh, meaning "Place of the Strong People." This transformation is more than a mere change of nomenclature; it is a profound declaration of identity, a testament to enduring resilience, and a living bridge connecting a deep past with a dynamic present.

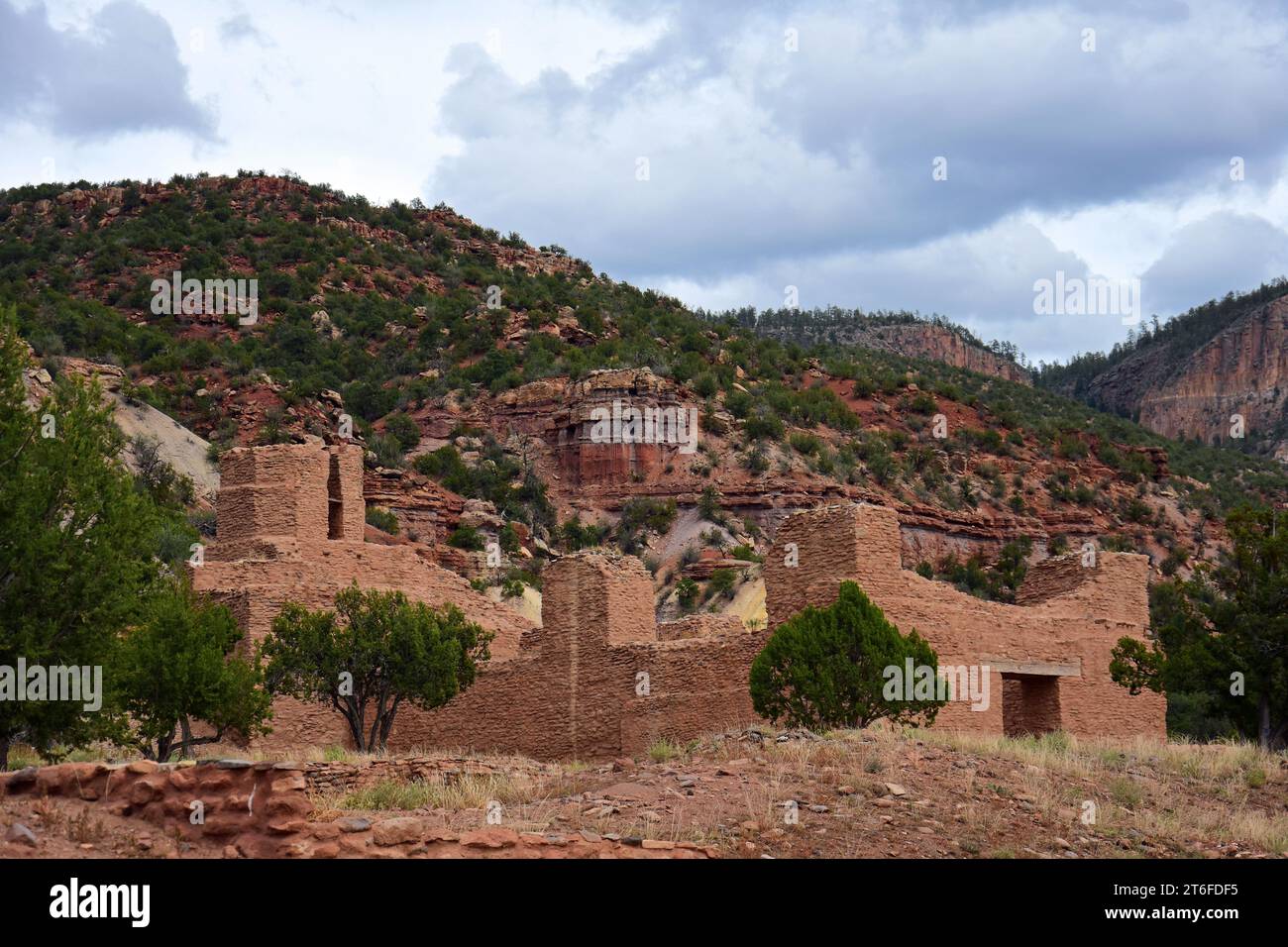

To understand Ohkay Owingeh is to journey through millennia of human history, adaptation, and unwavering cultural continuity. The Tewa people, ancestors of the modern residents, have inhabited this region for at least 800 years, with archaeological evidence suggesting a much longer presence in the wider Rio Grande valley. They were, and remain, sophisticated agriculturalists, harnessing the life-giving waters of the Rio Grande to cultivate corn, beans, and squash, staples that formed the bedrock of their society and spiritual beliefs. Their villages, constructed from the earth itself – adobe bricks rising organically from the landscape – were carefully planned around central plazas, focal points for community life, ceremony, and social gathering. These early communities were self-sufficient, complex societies with intricate social structures, deep spiritual practices, and a profound reverence for the land that sustained them.

The course of Ohkay Owingeh’s history took a dramatic turn in 1598 with the arrival of Don Juan de Oñate and his Spanish colonizers. This encounter, often romanticized in colonial narratives, marked the beginning of a new, often brutal, chapter for the Pueblo peoples of New Mexico. Oñate, seeking to establish a new Spanish colony, initially settled his expedition near Ohkay Owingeh, naming it "San Juan de los Caballeros" and briefly establishing it as the first European capital in what would become the United States. This period was characterized by forced labor, the imposition of Catholicism, and the suppression of indigenous spiritual practices. The Tewa people, while initially offering hospitality, soon found their way of life under severe threat.

"For generations, our people carried the burden of a name that wasn’t ours, a name given by those who sought to conquer us," explains a tribal elder, her voice resonant with history. "The Spanish came, they built their church, they told us to forget our gods and our language. But the memory of Ohkay Owingeh, the ‘Place of the Strong People,’ never faded from our hearts."

Despite the immense pressures, the Tewa people of Ohkay Owingeh, like their Pueblo relatives across the region, demonstrated incredible resilience. They adapted, often outwardly conforming to Spanish demands while secretly preserving their traditions, language, and spiritual beliefs. This duality, a masterful act of cultural survival, was a hallmark of the Pueblo experience. It culminated in the monumental Pueblo Revolt of 1680, a unified uprising that saw the Pueblo nations successfully expel the Spanish for twelve years – a remarkable victory against a colonial power. Ohkay Owingeh played a crucial, though often understated, role in this historic resistance.

Even after the Spanish reconquest, the name "San Juan Pueblo" persisted, a constant reminder of the colonial legacy. However, the seeds of reclaiming identity were continuously nurtured. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, as Native American nations across the United States asserted their sovereignty and cultural rights, the movement to restore the ancestral name gained momentum within Ohkay Owingeh. It was a decision born from decades of discussions, cultural revival efforts, and a deep-seated desire to honor their heritage.

The official change in 2005 was a moment of profound celebration and spiritual significance. "It was more than just changing a sign," says a former tribal governor. "It was a spiritual reawakening, a recognition of our true identity that had been suppressed for so long. It was about telling the world, and more importantly, telling ourselves, who we truly are: Ohkay Owingeh, the Place of the Strong People." This act solidified the Pueblo’s commitment to self-governance and cultural revitalization, paving the way for a future rooted firmly in its past.

Today, Ohkay Owingeh is a vibrant, living community of approximately 6,000 enrolled members. The physical landscape of the Pueblo still reflects centuries of tradition. Adobe homes, some centuries old, are clustered around the ancient plazas, their earthy tones blending seamlessly with the New Mexico high desert. The sound of the Tewa language, though challenged by the pervasive influence of English, can still be heard in homes and during ceremonies, a vital link to their ancestors. Efforts to preserve and teach Tewa to younger generations are ongoing and passionate, recognized as critical to the very soul of the community.

Cultural practices remain central to life at Ohkay Owingeh. The annual Feast Day of St. John the Baptist on June 24th, a date imposed by the Spanish but reinterpreted through Pueblo lenses, is a powerful demonstration of this fusion and continuity. It is a day of prayer, community, and spectacular traditional dances, such as the Corn Dance, performed by hundreds of participants in vibrant regalia. The rhythmic thud of moccasined feet on ancient earth, the resonant chants, and the intricate choreography tell stories of gratitude for the harvest, prayers for rain, and a deep connection to the natural world. These ceremonies are not mere performances; they are sacred rituals that reaffirm their spiritual relationship with the land and maintain the delicate balance of their universe.

Beyond the major Feast Day, other dances and ceremonies are held throughout the year, often away from public view, preserving their sanctity and spiritual power. The Pueblo’s artisans, while perhaps less globally renowned for pottery than some other Pueblos, continue to produce beautiful and culturally significant crafts, often incorporating traditional designs and techniques passed down through generations. The Ohkay Owingeh Arts and Crafts Cooperative provides a venue for local artists to share their work and preserve these artistic traditions.

Yet, Ohkay Owingeh is not a relic of the past; it is a dynamic, evolving community facing the complexities of the 21st century. Like many indigenous nations, it grapples with the delicate balance of preserving ancient traditions while navigating modern challenges. Economic development is a constant pursuit, aimed at creating opportunities for its members while maintaining cultural integrity. The Pueblo has invested in various enterprises, including agricultural initiatives, a casino, and other businesses, all designed to foster self-sufficiency and improve the quality of life for its people.

"Our ancestors faced Spanish invasion, drought, and countless hardships, yet they persisted," states a young tribal council member, reflecting on the future. "Today, we face new challenges: economic disparities, the erosion of language, the pull of the outside world. But the strength of Ohkay Owingeh, the spirit of our people, is our greatest resource. We are building a future that honors our past, educates our youth, and ensures our sovereignty for generations to come."

Education is a key focus, with many young people attending universities and bringing new skills and perspectives back to the Pueblo. Healthcare, infrastructure development, and environmental stewardship are also critical areas of tribal governance. The Pueblo remains a fierce advocate for its water rights, recognizing that the Rio Grande is not just a river but a sacred lifeline essential to their agricultural heritage and very existence.

In a world increasingly homogenized, Ohkay Owingeh stands as a powerful testament to the enduring human spirit and the strength of cultural identity. It is a place where ancient adobe walls whisper stories of resilience, where the Tewa language carries the wisdom of generations, and where the vibrant rhythm of traditional dance continues to beat at the heart of the community. The journey from San Juan Pueblo to Ohkay Owingeh is a narrative not of mere survival, but of profound reclamation, demonstrating that even after centuries of external pressures, the "Place of the Strong People" continues to thrive, evolve, and proudly assert its unique, eternal identity in the sacred landscape of New Mexico. Ohkay Owingeh is not just a destination; it is a living, breathing testament to the power of a people to remember who they are, and to forge their own future.