The Whispers of the Web: Unraveling the Ojibwe Dream Catcher’s Sacred Meaning

By [Your Name/Journalist’s Pen Name]

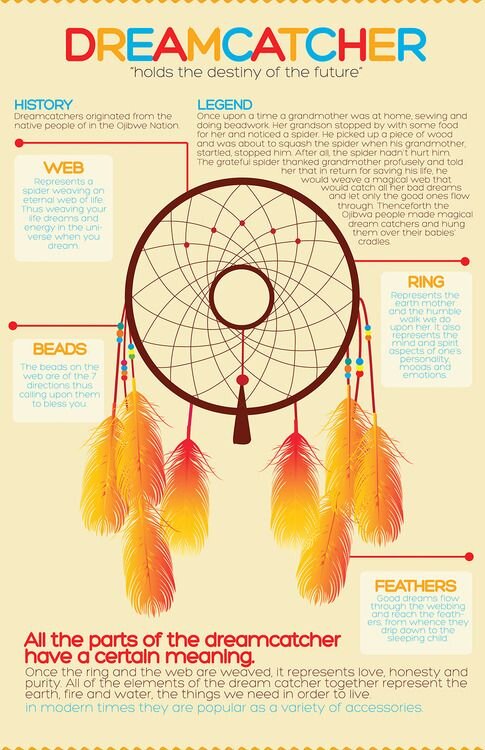

From roadside souvenir stalls to high-end boutiques, the dream catcher has become a globally recognized symbol. Its distinctive hoop, intricate web, and dangling feathers adorn bedrooms, cars, and even fashion accessories across continents. Yet, for many who admire its aesthetic appeal, the profound spiritual meaning and rich cultural heritage woven into its very threads remain largely unknown, obscured by decades of commercialization and cultural appropriation.

At its heart, the dream catcher is not merely a decorative object. It is a potent symbol, a spiritual tool, and a living prayer originating from the Ojibwe (Anishinaabe) people of North America. To understand its true essence is to embark on a journey into Indigenous wisdom, the sacred interconnectedness of life, and the delicate balance between the waking world and the realm of dreams.

The Ancient Origins: Asabikeshiinh and the Sacred Web

The story of the dream catcher, or asabikeshiinh (meaning "spider" in Ojibwe), is deeply rooted in Ojibwe cosmology and oral tradition. It is often linked to Asabikeshiinh, the Spider Woman, a benevolent maternal figure and protector of children, particularly infants. According to the legends, Asabikeshiinh was responsible for weaving a protective spiritual web over the cradleboards of babies, ensuring their safety and peaceful rest.

As the Ojibwe Nation grew and dispersed across vast territories, it became increasingly difficult for Asabikeshiinh to reach every child. So, she taught the grandmothers, mothers, and aunties how to weave these protective webs themselves. Using willow branches bent into a hoop and sinew or plant fibers for the web, they recreated her protective magic, hanging the finished pieces above the sleeping place of their young ones.

"The dream catcher was never just about catching bad dreams," explains Sarah Johnson, an Ojibwe elder and cultural educator from Ontario, Canada. "It was about connecting with the spirit world, about protecting our children’s innocence and guiding them as they learned about their place in creation. It was a tangible representation of Asabikeshiinh’s enduring love."

The original dream catchers were small, typically no larger than a child’s hand, and crafted from natural, perishable materials. The willow hoop, representing the circle of life, would eventually dry out and collapse, symbolizing the fleeting nature of childhood and the transition into adulthood, where the individual would then learn to navigate the dream world independently.

Decoding the Sacred Geometry: Elements and Their Meanings

Each component of an authentic Ojibwe dream catcher holds specific spiritual significance, working in harmony to fulfill its purpose:

-

The Hoop (Gii-zaasigizigaan): The Circle of Life

The circular shape of the hoop is paramount. It symbolizes the continuous flow of life, the sun and moon’s journey across the sky, and the interconnectedness of all beings within the Creator’s vast design. It represents the never-ending cycle of birth, death, and rebirth, and the constant movement of energy within the universe. Traditionally made from flexible willow branches, it embodies resilience and adaptability. -

The Web (Asabikeshiinh’s Net): The Filter of Dreams

Woven within the hoop, the intricate web is the heart of the dream catcher’s function. It is a spiritual filter. According to Ojibwe belief, the night air is filled with both good and bad dreams, as well as positive and negative energies. The web is designed to catch the latter. Nightmares, negative thoughts, and harmful energies become ensnared in the web’s intricate pattern, held there until the first rays of dawn. As the morning sun touches the dream catcher, these negative energies are said to evaporate, dissipating harmlessly into the morning light.Conversely, good dreams, positive thoughts, and beneficial energies know their way. They are believed to slip through the central opening of the web, sliding down the feathers to the sleeping person below. "The web is a metaphor for life itself," Elder Johnson elaborates. "It has holes, yes, but those holes are there for a reason – to let the good things through. It teaches us discernment, what to hold onto and what to let go of."

-

The Feathers (Miigwan): The Breath of Life and Guidance

Feathers, often from owls or eagles (though other birds’ feathers are used depending on availability and specific tribal practices), are not merely decorative. They are profoundly symbolic. Feathers represent breath and air, essential elements for life. They are believed to be the soft pathways through which good dreams descend gently to the dreamer. The gentle movement of the feathers in the breeze is a reminder of the unseen forces at play and the continuous flow of energy. For Indigenous peoples, feathers are also sacred gifts from the Creator, symbolizing wisdom, courage, and spiritual connection. -

The Beads (Manidoominens): The Spider and Good Omens

While not always present in every traditional dream catcher, beads often carry specific meanings. A single bead placed in the center of the web is sometimes believed to represent the spider itself – Asabikeshiinh – who is perpetually at work weaving her protective web. Other interpretations suggest beads represent good dreams that have been caught and blessed, or dew drops that symbolize the beauty and fragility of life. Sometimes, several beads are used to symbolize four directions or other sacred numbers.

Beyond Protection: A Spiritual Compass

The dream catcher’s spiritual significance extends beyond merely filtering dreams. It serves as a spiritual compass, guiding individuals through life’s journey. It fosters a connection to ancestral wisdom, reminding the dreamer of their heritage and the spiritual forces that watch over them. For the Ojibwe, dreams are not just random thoughts; they are often seen as messages from the spirit world, insights into the future, or guidance from ancestors. The dream catcher helps to clarify these messages, ensuring that only beneficial wisdom is received.

"It’s about spiritual well-being," notes Dr. Anton Treuer, an Ojibwe language and history scholar. "It creates a safe space for spiritual growth, for understanding oneself and one’s place in the universe. It’s a tool for self-reflection and healing."

The Pan-Indian Movement and the Double-Edged Sword of Popularity

While originating with the Ojibwe, the dream catcher’s popularity soared during the Pan-Indian movement of the 1960s and 70s. As Indigenous peoples from various nations sought to reclaim their identity and foster unity, the dream catcher became a widespread symbol of Indigenous pride and cultural resilience. Other tribes began adopting and adapting the craft, often incorporating their own specific symbols and materials, sharing in its protective essence.

However, this widespread adoption, particularly by non-Indigenous communities, also marked the beginning of its profound commercialization. Mass production, often in factories far removed from Indigenous lands, began to strip the dream catcher of its sacred meaning. Cheap materials, generic designs, and a complete disregard for the spiritual protocols involved in its creation became the norm.

"When you buy a dream catcher made in a factory overseas, you’re not getting a dream catcher," asserts an Indigenous artist from the Southwest. "You’re getting a decoration. It carries no spirit, no prayer, no connection to the land or the people who originated it. It’s empty."

This cultural appropriation is a significant concern for many Indigenous communities. It reduces a sacred object to a mere commodity, divorcing it from its intricate history, spiritual depth, and the very people who brought it into existence. It perpetuates a cycle where Indigenous cultural heritage is exploited for profit, while Indigenous artists and communities struggle to maintain their traditions and livelihoods.

Reclaiming Authenticity and Honoring the Spirit

Today, there is a powerful movement within Indigenous communities to reclaim the dream catcher’s authenticity. Indigenous artists, elders, and cultural educators are tirelessly working to preserve the traditional methods of crafting, teaching the profound spiritual meanings behind each element, and emphasizing the importance of ethical consumption.

For those who wish to connect with the true spiritual essence of the dream catcher, the message from Indigenous communities is clear: seek authenticity.

- Buy from Indigenous artists: Support creators who are members of Indigenous nations, who understand the cultural significance, and who craft their pieces with intention and respect. This ensures that the purchase directly benefits the communities that originated and preserved this sacred tradition.

- Educate yourself: Understand the history and spiritual meaning. Don’t just see it as a pretty object; see it as a cultural artifact imbued with deep spiritual significance.

- Respect the origins: Acknowledge that the dream catcher comes from a specific culture – the Ojibwe – and that its meaning is rooted in their worldview.

The Ojibwe dream catcher is far more than a decorative curio. It is a testament to the enduring wisdom of the Anishinaabe people, a spiritual guardian for children, a filter for dreams, and a powerful symbol of connection to the natural and spiritual worlds. By understanding and respecting its true origins and spiritual meaning, we can move beyond mere appreciation to a place of genuine reverence, honoring the whispers of the web and the profound legacy it represents. Its simple form belies a complex, beautiful, and deeply sacred narrative that continues to offer protection, guidance, and spiritual solace to those who truly understand its heart.