Manoomin’s Enduring Harvest: The Ojibwe Struggle for Wild Rice Sovereignty

Beneath the vast skies of the Great Lakes region, where lakes glitter like scattered jewels and forests whisper ancient secrets, a quiet but profound battle is being waged. It is a struggle not over land or gold, but over a sacred grain: Manoomin, or wild rice (Zizania aquatica). For the Ojibwe people (Anishinaabe), Manoomin is more than just food; it is a spiritual relative, a cultural cornerstone, and a living testament to their enduring sovereignty, enshrined in treaties that predate statehood.

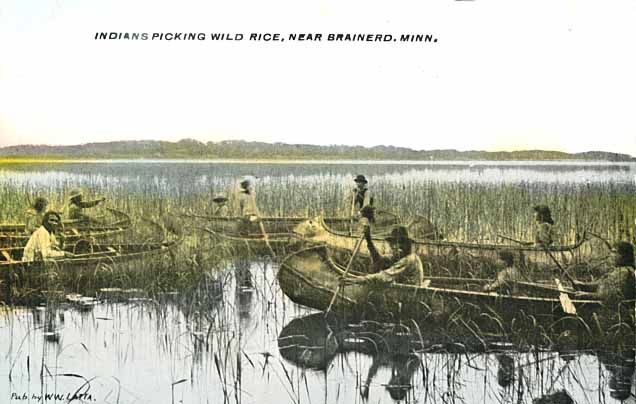

The act of harvesting Manoomin is a ritual passed down through generations. In late summer, as the rice kernels ripen, Ojibwe harvesters glide through the shallow waters in canoes, using long, slender "knocking sticks" to gently bend the stalks over the canoe and tap the ripe grains into the boat. This traditional method ensures that not all grains are collected, allowing some to fall back into the water to reseed for future seasons – a practice rooted in sustainable stewardship and deep ecological knowledge.

A Sacred Staple and a Prophecy Fulfilled

Manoomin is central to the Ojibwe creation story and migration narrative. Oral traditions speak of the Anishinaabe being told to journey westward until they found "food that grows on water." This prophecy led them to the Great Lakes region, where they discovered the abundant wild rice beds that sustained their communities for centuries. "Manoomin is a gift from the Creator," explains Frank Bibeau, a tribal attorney and member of the White Earth Band of Ojibwe. "It’s part of our identity, our history, and our future. Without it, we lose a piece of who we are."

Historically, Manoomin was a critical food source, rich in nutrients, that allowed Ojibwe communities to thrive through harsh winters. It was also a vital trade item, fostering economic networks across the continent. Beyond sustenance, the rice beds themselves are critical ecosystems, providing habitat for countless species of waterfowl, fish, and invertebrates, contributing to the overall health of the wetlands.

The Bedrock of Rights: Treaties and Ceded Territories

The foundation of the Ojibwe’s right to harvest Manoomin lies in a series of treaties signed with the U.S. government in the 19th century, notably the Treaties of 1837, 1842, and 1854. In these agreements, the Ojibwe ceded vast tracts of their ancestral lands, encompassing much of what is now Wisconsin, Michigan, and Minnesota. Crucially, however, they reserved specific rights – the right to hunt, fish, and gather on these ceded territories. These are known as "usufructuary rights," meaning the right to use and benefit from the land, even if ownership has changed.

For decades, state governments in Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Michigan challenged these rights, asserting their own regulatory authority over hunting, fishing, and gathering. This led to a series of protracted legal battles, culminating in a landmark victory for the Ojibwe. In 1983, in Lac Courte Oreilles v. Wisconsin (often referred to as LCO III), the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit affirmed the Ojibwe’s reserved treaty rights. The court ruled that these rights were never extinguished and that the Ojibwe retained the right to harvest resources, including wild rice, in their ceded territories, subject only to conservation measures necessary for public safety or resource preservation.

"Our treaties are not just historical documents; they are living agreements," asserts John Johnson Sr., former President of the Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa. "They define who we are and our relationship with this land. The courts affirmed what we always knew: these rights were never given up."

Contemporary Threats: Beyond Legal Battles

While legal victories have affirmed their rights, the Ojibwe face a new generation of threats to Manoomin, many of which are existential. These challenges extend beyond state regulations to encompass environmental degradation, climate change, and the relentless march of industrial development.

One of the most pressing concerns is habitat destruction. Wild rice is highly sensitive to water quality and depth. Agricultural runoff, industrial pollution, and shoreline development have significantly degraded many traditional rice beds. Furthermore, climate change poses an insidious threat. Changing precipitation patterns, increased temperatures, and more frequent extreme weather events disrupt the delicate balance required for Manoomin to thrive. Altered water levels can drown young plants or expose fragile roots, while warmer waters can encourage invasive species that outcompete the native rice.

Perhaps the most visible and controversial threat comes from proposed and existing infrastructure projects, particularly oil pipelines. The Enbridge Line 5 pipeline, for instance, which runs beneath the Straits of Mackinac and through northern Wisconsin and Michigan, poses a catastrophic risk to countless wild rice beds. A rupture could devastate vast areas of wetlands, poisoning the very waters Manoomin needs to survive. Ojibwe tribes have been at the forefront of the fight against Line 5, seeing it as a direct threat to their cultural survival. "When you threaten the water, you threaten Manoomin," states a representative from the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, whose reservation is directly in the pipeline’s path. "And when you threaten Manoomin, you threaten our people."

Commercial harvesting also presents a challenge. Non-Native commercial harvesters, often using more aggressive methods than traditional Ojibwe practices, can deplete beds and damage the ecosystem. While state regulations attempt to manage this, the conflict often highlights the differing philosophies between profit-driven extraction and traditional stewardship.

The Ojibwe Response: Stewardship, Self-Governance, and Resilience

In the face of these formidable challenges, the Ojibwe people are not passive victims. They are actively engaged in defending Manoomin through a multi-pronged approach that combines legal action, political advocacy, traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), and cultural revitalization.

Tribes are investing in their own natural resource departments, monitoring water quality, restoring degraded rice beds, and managing harvests according to traditional practices. They are using their inherent sovereign authority to assert control over their territories and resources, often pushing for co-management agreements with state and federal agencies. These agreements acknowledge tribal expertise and ensure that conservation efforts are culturally appropriate and effective.

Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) is proving invaluable in understanding and protecting Manoomin. Generations of observation have given Ojibwe elders and harvesters an intimate understanding of the rice’s life cycle, its relationship with water and climate, and the subtle indicators of ecosystem health. This knowledge, often dismissed by Western science, is now being recognized as critical for climate adaptation and environmental remediation.

Moreover, the struggle for Manoomin has galvanized cultural revitalization efforts. Language immersion programs teach children the Ojibwe words for the rice and the stories associated with it. Community events center around the harvest, bringing families together to share knowledge and practice traditions. These efforts strengthen tribal identity and ensure that the spiritual connection to Manoomin is passed on to future generations.

In 2021, a groundbreaking legal precedent was set when the White Earth Band of Ojibwe formally recognized the "Rights of Manoomin" as having legal standing, capable of suing for its own protection in tribal court. This "Rights of Nature" approach, while still nascent, represents a powerful assertion of indigenous legal philosophy and a bold step in safeguarding the environment.

Looking Forward: A Shared Future

The fight for Manoomin’s future is far from over. It is a testament to the Ojibwe people’s unwavering commitment to their cultural heritage, their treaty rights, and the ecological health of the Great Lakes region. Their struggle highlights a broader truth: the well-being of indigenous communities is inextricably linked to the health of the land and its resources.

For non-Native populations, understanding the Ojibwe’s fight for Manoomin means more than just acknowledging treaty rights; it means recognizing the profound wisdom embedded in traditional ecological knowledge and the critical role indigenous peoples play in environmental stewardship. It is a call to move beyond mere tolerance to genuine respect and collaboration.

As the wild rice beds sway gently in the breeze, they carry not just the promise of a harvest, but the enduring spirit of the Ojibwe people. Their fight for Manoomin is a powerful reminder that true sovereignty is not just about political boundaries, but about the right to sustain a way of life, protect sacred traditions, and ensure that future generations can continue to gather the "food that grows on water" – a gift from the Creator, preserved through generations of resilience and unwavering dedication.