Ojo Caliente Canyon: The Crucible of Victorio’s War and Apache Defiance

In the rugged, sun-baked heart of New Mexico, where canyons carve deep scars into the earth and mesas rise like ancient sentinels, lies Ojo Caliente Canyon. It is a place of stark beauty and profound historical significance, a landscape etched forever with the memories of a brutal and desperate conflict. Not a single, decisive battle in the conventional sense, Ojo Caliente Canyon served as a crucible for a prolonged and agonizing struggle during the late 19th-century Apache Wars, particularly becoming the focal point of the legendary Warm Springs Apache leader Victorio’s defiant stand against overwhelming American forces. Here, the very terrain became an ally for the Apache and an unforgiving adversary for the U.S. Army, encapsulating the tenacity of a people fighting for their homeland and the relentless advance of an expanding nation.

The story of Ojo Caliente Canyon is inextricably linked to the broader narrative of the Apache Wars, a series of conflicts spanning several decades that pitted various Apache bands against the United States Army and Mexican forces. At its core, these wars were a tragic clash of cultures, fueled by broken treaties, forced relocations, and a fundamental misunderstanding of land and sovereignty. For the Apache, land was not merely property but the source of their spiritual and physical sustenance, the resting place of their ancestors, and the very essence of their identity. For the burgeoning American nation, the vast, resource-rich territories of the Southwest represented opportunity, expansion, and the fulfillment of Manifest Destiny.

Central to the events at Ojo Caliente was Victorio, a Mimbres Apache war chief of immense courage, strategic brilliance, and an unwavering commitment to his people’s freedom. Born around 1825, Victorio had witnessed decades of conflict and betrayal. His band, the Warm Springs (or Ojo Caliente) Apache, had long considered the hot springs area of Ojo Caliente their ancestral home. It was a place of healing, a vital water source in an arid land, and a natural fortress.

However, the U.S. government, in its effort to "civilize" and control Native American populations, implemented a reservation policy that proved disastrous for the Apache. Time and again, promises of secure homelands were broken. Victorio and his people were repeatedly moved, most notably to the arid, disease-ridden San Carlos Reservation in Arizona. This move, in 1877, was the ultimate indignity. San Carlos was a desolate place, shared with rival Apache bands, and rife with corruption and inadequate supplies. It was a prison, not a home.

"To be driven from one’s homeland, to be confined to a place alien and hostile, was an intolerable affront to the Apache spirit," noted historian Dan L. Thrapp in his seminal work on the Apache Wars. "For Victorio, a man of profound dignity and fierce independence, San Carlos was a slow death sentence."

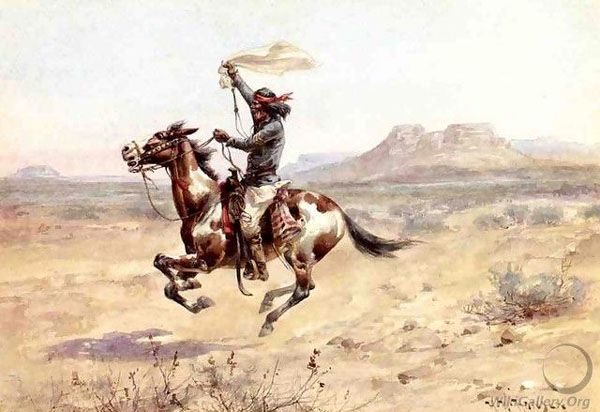

It was this desperation that ignited Victorio’s War. In August 1879, Victorio, along with his sister Lozen (a revered warrior and prophetess) and his trusted lieutenant Nana, led approximately 100-150 men, women, and children in a daring escape from San Carlos. Their objective: to return to Ojo Caliente and reclaim their ancestral lands. This act of defiance marked the beginning of one of the most remarkable campaigns of guerrilla warfare in American history.

The U.S. Army, under the command of Brigadier General Edward Hatch, commander of the Department of New Mexico, was immediately tasked with tracking down Victorio. The chase became a relentless, grueling odyssey across the vast, unforgiving landscape of New Mexico, Arizona, and later, Texas and Mexico. Ojo Caliente Canyon, with its intricate network of arroyos, hidden springs, and towering bluffs, became a strategic hub for Victorio’s operations. It was a place he knew intimately, a natural stronghold where he could ambush pursuing troops, replenish supplies, and plan his next moves.

The canyon itself, a labyrinth of natural defenses, proved to be an insurmountable obstacle for the Army’s conventional tactics. Troopers, often weighed down by heavy equipment and unfamiliar with the terrain, struggled against an enemy who moved like ghosts. Victorio’s tactics were brilliant: swift raids on ranches and settlements to acquire horses and supplies, followed by rapid retreats into the mountains. He rarely engaged in pitched battles, preferring ambushes and hit-and-run tactics that capitalized on his warriors’ superior mobility and knowledge of the land.

"The Apache, with their intimate knowledge of the land, moved with an almost supernatural speed," one exasperated officer reportedly noted in his dispatches. "They are everywhere and nowhere, appearing from the very earth and vanishing into thin air."

Throughout late 1879 and early 1880, numerous skirmishes and desperate chases unfolded in and around Ojo Caliente. Small detachments of cavalry and infantry were constantly on Victorio’s trail, but he consistently outmaneuvered them. On one notable occasion in September 1879, Victorio ambushed a detachment of the 9th Cavalry (Buffalo Soldiers) near the Black Range, inflicting casualties before melting back into the mountains. The Buffalo Soldiers, African American regiments of the U.S. Army, were highly respected by the Apache for their bravery and tenacity, often being the ones tasked with the most dangerous pursuits.

The terrain around Ojo Caliente provided Victorio with countless advantages. The steep canyon walls offered perfect vantage points for ambushes, allowing his warriors to rain down fire on unsuspecting troops from above. The numerous caves and hidden alcoves provided shelter and storage for their limited supplies. The hot springs themselves offered vital water and, for a time, a place of rest and spiritual rejuvenation for the beleaguered Apache.

The pressure on the U.S. Army mounted with each successful raid and evasion by Victorio. Public outcry from settlers demanding protection increased, leading to a massive military response. By the spring of 1880, General Hatch had assembled a force of nearly 2,000 soldiers, including elements of the 6th and 9th Cavalry, and the 15th Infantry, specifically tasked with hunting down Victorio. This was a substantial force for the era, highlighting the military’s frustration and determination to end Victorio’s rebellion.

Despite the overwhelming numbers, Victorio continued to elude capture. He would often divide his band into smaller groups, making them even harder to track. His warriors, though few in number, were seasoned veterans, masters of survival, and fighting for their lives and families. They moved silently, read the landscape like a book, and fought with the ferocity of cornered animals.

While Ojo Caliente Canyon was never the site of a single, climactic battle that ended Victorio’s War, it represented the heart of his resistance. It was the land he fought for, the strategic base from which he launched his raids, and the sanctuary he desperately sought to hold. The relentless pressure from the U.S. Army, however, eventually forced Victorio and his band to abandon Ojo Caliente as a permanent base. They were harried eastward into the Black Range, then south into the forbidding deserts of Texas and Mexico, constantly pursued by both American and Mexican forces.

The campaign around Ojo Caliente highlighted the profound difficulties of fighting an enemy deeply embedded in their own territory. The U.S. Army, despite its superior firepower and numbers, struggled with logistics, unfamiliarity with the landscape, and the sheer elusiveness of the Apache. It was a war of attrition, marked by grueling marches, ambushes, and the constant psychological strain of chasing a seemingly invisible foe.

Victorio’s War, largely centered around the strategic importance of Ojo Caliente and the surrounding mountains, finally came to a tragic end in October 1880, not in New Mexico, but far to the south in Tres Castillos, Mexico. There, Victorio and many of his warriors were cornered and killed by Mexican troops. His death, however, did not immediately end the Apache Wars. His successor, the venerable and equally cunning Nana, continued the fight with a smaller band, demonstrating the same indomitable spirit and masterful guerrilla tactics that had characterized Victorio’s campaigns. The echoes of Victorio’s defiance reverberated through subsequent Apache resistance, notably inspiring Geronimo’s later breakouts.

Today, Ojo Caliente Canyon remains a potent symbol of this period. The hot springs still flow, providing solace and healing, much as they did for the Apache centuries ago. But the land also whispers tales of hardship, courage, and sorrow. It is a testament to Victorio’s extraordinary leadership and the Apache people’s unwavering determination to protect their way of life against overwhelming odds. The battles and skirmishes fought in and around Ojo Caliente Canyon were not just military engagements; they were a desperate struggle for survival, a poignant chapter in the tragic story of the American West, where the pursuit of expansion collided violently with the deeply rooted sovereignty of indigenous peoples. The scars on the land, like the scars on history, serve as a stark reminder of the human cost of conflict and the enduring spirit of defiance.