The Unsung Canvas: John Margolies and the Enduring Art of America’s Roadside

Imagine a time before GPS, before every turn-off was meticulously mapped on a glowing screen, when the open road was an invitation to discovery, and the landscape unfolded like a vast, quirky art gallery. Amidst the blur of passing fields and forests, unexpected structures would erupt from the mundane: a giant duck selling eggs, a coffee pot serving coffee, a pagoda-shaped gas station, or a diner gleaming like a chrome spaceship. These weren’t just buildings; they were exuberant, often anonymous, declarations of commerce and imagination, designed to stop you in your tracks.

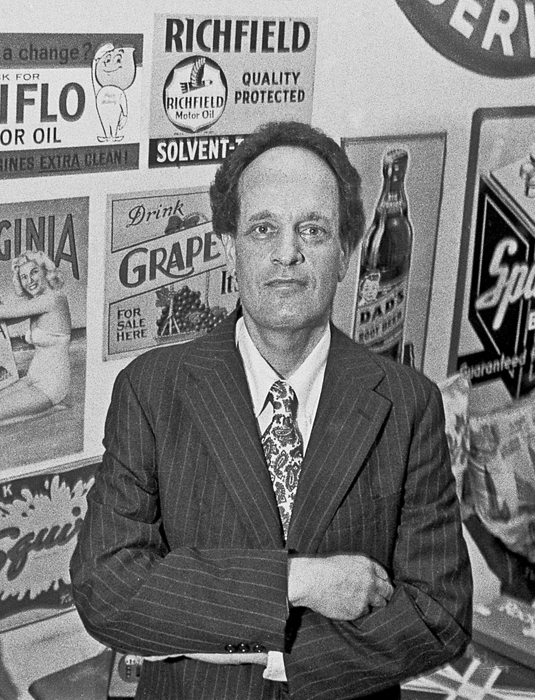

For decades, while mainstream architectural critics championed the austere lines of modernism and dismissed these vernacular wonders as mere kitsch, one man saw them with different eyes. John Margolies, born in 1940, was not just a photographer; he was an archaeologist of the everyday, a tireless chronicler of the forgotten, and a visionary who single-handedly elevated the gaudy, the garish, and the glorious structures of America’s roadside into a legitimate subject of study and admiration. He was the quiet revolutionary who taught us to look again at what we thought we knew about American design.

Margolies’ journey into the heart of America’s visual cacophony began not with a camera, but with a profound dissatisfaction with conventional architectural discourse. A graduate of the University of Pennsylvania and Syracuse University, he initially pursued a path in architecture and design. However, he quickly became disenchanted with the prevailing academic snobbery that dismissed anything outside the established canon of “good taste.” He found the sterile, often elitist, world of high architecture blind to the vibrant, spontaneous expressions of popular culture that defined so much of the American experience.

“I was interested in what was not designed by architects, but by the people who owned them,” Margolies once remarked, encapsulating his core philosophy. He saw an authenticity, a raw creativity, in these roadside attractions that he felt was missing from the carefully curated, often intellectualized, designs celebrated in galleries and textbooks. His was a democratic vision, one that found beauty and meaning in the roadside diner, the neon sign, and the programmatic building shaped like a hot dog or an ice cream cone.

Starting in the late 1960s and intensifying through the 1970s and 80s, Margolies embarked on an extraordinary quest. He crisscrossed the United States multiple times, driving tens of thousands of miles in his Volkswagen bus, armed with a meticulously organized system and, crucially, a large-format 4×5 camera. This wasn’t a casual hobby; it was a disciplined, almost monastic, pursuit. He photographed each structure head-on, in natural light, often against a clear blue sky, stripping away distractions to present the buildings as pure, sculptural forms. His approach was disarmingly simple, yet profoundly effective, allowing the inherent character and audacious design of each subject to speak for itself.

His method was a ritual. He would often arrive at dawn or dusk to capture the best light, waiting patiently for cars or people to clear the frame. He was not interested in social commentary or candid moments, but in the building itself, isolated and monumentalized. The resulting images are striking in their clarity and often surprising in their aesthetic impact, transforming what many perceived as “junk” into compelling visual art.

Margolies categorized his findings with the precision of an archivist. He documented everything from gas stations designed like miniature temples to motels shaped like teepees, from monumental signs advertising roadside attractions to diners that promised a slice of Americana. He was particularly fascinated by “programmatic architecture,” a term he helped popularize, referring to buildings literally shaped to represent their function or what they sold. The iconic Big Duck in Flanders, New York, a poultry shop built in 1931 in the form of a giant duck, became a prime example of this whimsical, yet highly effective, marketing strategy. These structures were not just shelters; they were advertisements made manifest, designed to catch the fleeting attention of motorists speeding by.

His work resonated with the burgeoning Pop Art movement of the era, which similarly sought to elevate the mundane and commercial into the realm of fine art. Just as Andy Warhol transformed soup cans and Brillo boxes into iconic imagery, Margolies’ lens, stripped these roadside objects of their commercial context and presented them as pure form, pure color, pure American expression. He wasn’t simply documenting; he was recontextualizing, forcing viewers to confront their own biases about what constituted “art” or “architecture.”

The fruit of his labors began to appear in influential publications and exhibitions. His seminal book, The End of the Road: Vanishing America (1981), was a poignant collection of his roadside photographs, many capturing structures on the brink of demolition. This was followed by Pumping Gas: Gas Stations of America (1979), America Waits (1991), and Roadside America (1995), among others. These books were not merely photo albums; they were visual manifestos, challenging the prevailing notions of taste and contributing significantly to the growing field of cultural studies.

Ironically, Margolies himself wasn’t a vocal preservationist in the traditional sense; his mission was primarily documentation. He understood the transient nature of these structures, often built quickly and cheaply, designed for a fleeting moment in the automotive age. Yet, in documenting, he inadvertently became one of preservation’s greatest allies. His photographs captured these buildings in their prime, creating an invaluable historical record of an architectural style that was rapidly disappearing due to highway expansion, changing commercial trends, and a general lack of appreciation. Many of the buildings he photographed exist today only in his images, having fallen victim to the wrecking ball or the ravages of time.

Beyond the aesthetic appeal, Margolies’ work offers a fascinating sociological insight into mid-20th century America. These roadside structures were a direct product of the post-war economic boom, the rise of the automobile, and the burgeoning American consumer culture. They represented an optimism, a boundless creativity, and a uniquely American spirit of enterprise that flourished along the newly paved highways connecting towns and cities. They were democratic architecture, accessible to all, and reflective of a collective desire for novelty and convenience.

Behind the vibrant, often humorous imagery was a man of quiet intensity. Margolies was known for his unassuming demeanor, his meticulousness, and his unwavering dedication to his subject. He was not seeking fame or fortune, but simply to share his unique vision and to ensure that these fascinating, often overlooked, pieces of American history were not lost to time. His vast archive, comprising over 11,000 prints and 17,000 slides, was acquired by the Library of Congress in 2008, a testament to the profound cultural and historical significance of his work. This collection ensures that future generations can continue to explore the idiosyncratic beauty of America’s roadside through his discerning eye.

John Margolies passed away in 2016, but his legacy endures. He didn’t just photograph buildings; he documented a moment in the American psyche, a period of exuberant commercialism and boundless creativity. He opened the eyes of architects, historians, artists, and the general public to the rich tapestry of vernacular design that permeates the American landscape. He challenged the narrow definitions of what constitutes valuable architecture and showed us that true artistry can be found in the most unexpected places – along the highways and byways, where ingenuity and ambition collide with everyday life.

In a world increasingly homogenized by corporate branding and global design trends, Margolies’ work serves as a vibrant reminder of a more playful, inventive, and wonderfully strange era. He reminds us to slow down, look closely, and appreciate the often-overlooked wonders that line our roads, each a testament to human ingenuity and the enduring spirit of America’s open road. His photographs are not just historical records; they are an invitation to rediscover the art that surrounds us, if only we are willing to see it.