Echoes of Anhaica: The Enduring Legacy of the Apalachee Nation

By [Your Name/Journalist’s Name]

The name “Apalachee” resonates with a strange familiarity in the American South. It graces counties, rivers, and bays across Florida, Georgia, and Alabama. Yet, for many, the people behind the name remain a shadowy footnote in history, a vanished tribe from a forgotten past. But the story of the Apalachee is far from vanished; it is a compelling, often tragic, narrative of a powerful indigenous nation, their clash with European empires, their near-annihilation, and their remarkable, if often invisible, resilience.

Once the dominant force in what is now the Florida Panhandle, the Apalachee were a sophisticated, agricultural society whose influence stretched far beyond their fertile fields. Their journey through history is a microcosm of the broader Indigenous experience in North America: a testament to cultural richness, the devastating impact of colonialism, and the enduring spirit of a people who refused to be erased.

Masters of the Fertile Lands: A Pre-Contact Powerhouse

Before the arrival of Europeans, the Apalachee flourished in the rich, loamy soils of the Red Hills region, an area stretching from the Aucilla River in the east to the Ochlockonee River in the west, and south to the Gulf of Mexico. Their strategic location, abundant natural resources, and highly organized society made them one of the most powerful Mississippian chiefdoms in the Southeast.

“They were a very well-organized, large, and successful agricultural society,” notes Dr. Rochelle Marrinan, an archaeologist who has extensively studied the Apalachee. “Their cornfields stretched for miles, providing a surplus that supported a dense population and robust trade networks.” Indeed, the Apalachee were master farmers, cultivating vast fields of corn, beans, and squash, which sustained a population estimated to be between 30,000 and 60,000 people. Their agricultural prowess was so renowned that later Spanish chroniclers would marvel at the productivity of their lands.

Their society was hierarchical, led by powerful chiefs and supported by a priestly class. They built impressive ceremonial mounds, such as those found at the Lake Jackson Mounds Archaeological State Park near Tallahassee, which served as centers for religious rituals and elite residences. These mounds, some towering over 30 feet high, are silent witnesses to a complex culture that thrived for centuries.

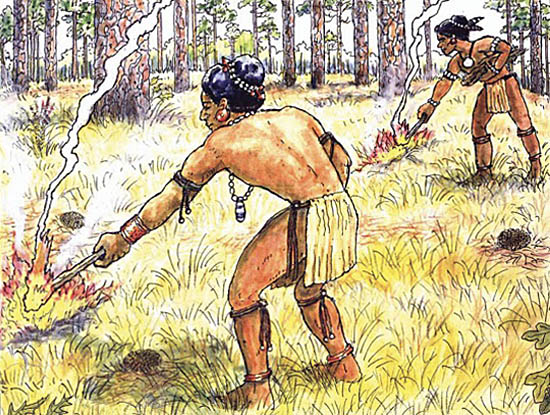

Beyond agriculture and monumental architecture, the Apalachee were also known for their fierce warrior tradition and a distinctive, often brutal, ball game. This game, played with a small, hard deerskin ball, involved two teams of up to 40-50 men, attempting to hit a target on a pole. It was a ritualistic contest, deeply intertwined with their spiritual beliefs, that could last for days and often resulted in severe injuries or even death. Betting was intense, and entire villages would gather to watch, demonstrating the social cohesion and competitive spirit of the Apalachee.

The Shadow of Europe: First Encounters and Brutal Consequences

The Apalachee’s world began to irrevocably change with the arrival of Europeans in the 16th century. The first significant contact came in 1528 with the ill-fated expedition of Pánfilo de Narváez. Narváez, seeking gold and glory, marched his starving, disease-ridden men into Apalachee territory, where they met fierce resistance. The Apalachee, unyielding in their defense, inflicted heavy casualties, forcing Narváez to retreat to the coast, where he and most of his men perished in a disastrous attempt to sail to Mexico. This initial encounter established a pattern of hostility and mutual distrust.

A decade later, in 1539, Hernando de Soto led a far larger and better-equipped expedition into Apalachee lands. De Soto’s chroniclers described the Apalachee capital, Anhaica, as a substantial town of 250 large houses, surrounded by immense fields of corn. One chronicler, known as the Gentleman of Elvas, wrote of the land: “This land was well cultivated and very fertile, where there was much corn, squash, beans, and plums, which are native to the country.”

Despite the bounty, De Soto’s presence was catastrophic. He wintered in Anhaica, exploiting Apalachee labor, raiding their food stores, and subjecting them to brutal treatment. Though the Apalachee fought back valiantly, their stone-tipped weapons were no match for Spanish steel and gunpowder. More devastating than open warfare, however, were the invisible enemies the Europeans carried: diseases like smallpox, measles, and influenza, against which the Indigenous people had no immunity. These epidemics swept through Apalachee communities, decimating their population and weakening their social fabric.

The Mission Era: A New Form of Conquest

After decades of sporadic contact and further disease outbreaks, the Spanish returned to Apalachee territory in the early 17th century, this time with a new strategy: the mission system. Beginning in 1633, Franciscan friars established a chain of missions, stretching along what became known as the “Camino Real” (Royal Road), connecting St. Augustine to the Apalachee heartland. By the 1670s, there were over a dozen missions, ministering to thousands of Apalachee converts.

The Apalachee’s reasons for embracing the missions were complex. While some may have genuinely been drawn to the new religion, others likely saw strategic advantages: access to Spanish trade goods, protection from rival tribes (like the Creek), or perhaps even a desperate hope that the Spanish priests could offer some spiritual remedy to the relentless diseases.

Life under the missions, however, was a mixed blessing. While it brought a period of relative stability and some new technologies, it also came at a steep cost. Apalachee men and women were subjected to the repartimiento system, a form of forced labor where they were compelled to work for the Spanish, transporting goods to St. Augustine or building colonial structures. Their traditional spiritual practices were suppressed, their social structures undermined, and their cultural identity slowly eroded. The missions, in essence, became a new form of colonial control, further integrating the Apalachee into the Spanish imperial system while simultaneously dismantling their ancient way of life.

The Apalachee Massacre: A Cataclysmic End

The fragile peace of the mission era shattered with the outbreak of Queen Anne’s War (1702-1713), a larger geopolitical conflict between England and Spain. The English colony of Carolina, eager to expand its territory and capture Native American slaves, launched devastating raids into Spanish Florida. In 1704, Governor James Moore of Carolina led a force of some 50 English colonists and over 1,000 allied Creek warriors into the heart of Apalachee Province.

What followed was a campaign of unparalleled brutality. Moore’s forces systematically attacked and burned the Spanish missions and Apalachee towns. The Apalachee, caught between two warring European powers, suffered immense losses. Many were killed in battle, others were massacred, and thousands were taken captive and sold into slavery in Carolina and the Caribbean.

Moore himself, in a letter to the Lords Proprietors of Carolina, chillingly described his campaign: “We have killed and taken captive above 4,000 souls… and this whole country of Apalachee is now reduced to so few people that it is not worth the charge of keeping.” This “Apalachee Massacre” effectively destroyed the Apalachee nation as an independent entity, scattering its survivors and dismantling a centuries-old civilization in a matter of months.

Dispersal, Resilience, and Reclaiming Identity

The survivors of the 1704 raids were dispersed in every direction. Some fled west, seeking refuge with the French at Mobile and later settling in Louisiana. Others sought protection from the Spanish in Pensacola or St. Augustine, only to face further hardships. Still others were absorbed into Creek communities, their distinct identity slowly fading through intermarriage and assimilation.

For nearly three centuries, the Apalachee were considered “extinct” by many historians, their name a mere echo in the landscape. However, the story of the Apalachee is not one of complete disappearance, but of remarkable resilience and quiet survival. Descendants of those who fled to French Louisiana managed to maintain aspects of their heritage, often intermarrying with other Native American groups, such as the Tunica and Biloxi, or with French and Spanish settlers.

Today, these descendants are actively working to reclaim and revitalize their Apalachee identity. The Talimali Band of Apalachee in Louisiana, for example, represents a significant effort to bring the Apalachee name back into the light. They are a state-recognized tribe in Louisiana, working diligently to preserve their language, traditions, and history.

“We were never truly gone,” states Gil St. Cyr, Chairman of the Talimali Band of Apalachee. “Our ancestors carried our stories and our spirit in their hearts, even when they had to hide who they were. Now, it’s our responsibility to ensure that the world knows the Apalachee are still here, and our history is a vital part of the American story.”

Their efforts include historical research, cultural education, and advocating for broader recognition of their heritage. They are a living testament to the fact that cultural annihilation, though often intended, is rarely absolute.

The story of the Apalachee is a powerful reminder of the profound impact of colonial encounter. It is a narrative that begins with a thriving, complex society, moves through periods of violent conflict and cultural transformation, and ultimately arrives at a present day where descendants are actively working to reconstruct and celebrate a heritage that was nearly lost. The name “Apalachee” on maps across the Southeast is more than just a place-name; it is a whisper from the past, a call to remember a powerful people whose echoes still resonate, and whose journey of resilience continues.