Okay, here is a 1,200-word journalistic article in English about the Nez Perce Historic Trail.

Echoes of the Nimiipuu: Walking the Nez Perce Historic Trail, A Journey of Resilience and Remembrance

The wind whispers through the towering pines of the Bitterroot Mountains, a sound that has echoed for millennia. It carries the scent of pine needles and damp earth, and if you listen closely, perhaps the faint hoofbeats of ponies and the determined footsteps of a people fighting for their very existence. This is the Nez Perce Historic Trail, or as the Nimiipuu (the Nez Perce people) know it, the Nee-Me-Poo Trail – a 1,170-mile odyssey across four states, a testament to courage, desperation, and an enduring spirit.

More than just a path through the wilderness, the Nez Perce Historic Trail is a scar on the American landscape, etched by the forced removal and desperate flight of the non-treaty Nez Perce bands in 1877. It’s a living outdoor museum, a somber classroom, and a profound pilgrimage for those seeking to understand one of the most tragic and compelling chapters in U.S. history.

The Genesis of Conflict: Land, Gold, and Broken Promises

Before the arrival of European settlers, the Nimiipuu were a powerful and prosperous nation, their ancestral lands stretching across parts of what are now Oregon, Washington, and Idaho. They were renowned horse breeders, skilled hunters, and adept diplomats, living harmoniously with the land, following the seasonal cycles of salmon runs, camas root harvests, and buffalo hunts. Their name, Nez Perce (pierced nose), was given by French traders, though the practice was not widespread among them. They called themselves "Nimiipuu," meaning "The People."

Their first encounters with Euro-Americans were largely peaceful. Lewis and Clark received crucial aid from the Nimiipuu in 1805, forging a bond of respect. However, as the 19th century progressed, the insatiable hunger for land, fueled by Manifest Destiny and the discovery of gold, brought increasing pressure. A series of treaties, notably the Treaty of 1855, significantly reduced Nimiipuu lands but still preserved their cherished Wallowa Valley in Oregon.

The real trouble began with the Treaty of 1863. After gold was discovered on their reservation lands, U.S. commissioners demanded a new treaty, shrinking the Nimiipuu territory by nearly 90 percent, to just one-tenth of its 1855 size. Many bands, including those led by Chief Joseph (Heinmot Tooyalakekt, "Thunder Rolling Down the Mountain"), Chief Looking Glass, and Chief White Bird, refused to sign, arguing that the chiefs who did sign had no authority to sell communal lands. They became known as the "non-treaty" Nez Perce.

For years, Chief Joseph eloquently pleaded his people’s case to U.S. authorities, even traveling to Washington D.C. His powerful words resonated with some, but ultimately fell on deaf ears. In 1877, General O.O. Howard, known as "The Christian General," was ordered to enforce the removal of the non-treaty bands to the much smaller Lapwai Reservation in Idaho. They were given 30 days to leave their ancestral lands.

The Flight for Freedom: 1,170 Miles of Desperation

The forced exodus began in May 1877, a period of immense sorrow and upheaval. As the Nimiipuu gathered at Camas Prairie, a tragic misunderstanding escalated into violence. A small group of young Nez Perce warriors, enraged by the injustice and the murder of a tribal member, retaliated against white settlers. This act irrevocably shattered any hope of peaceful relocation and ignited what became known as the Nez Perce War.

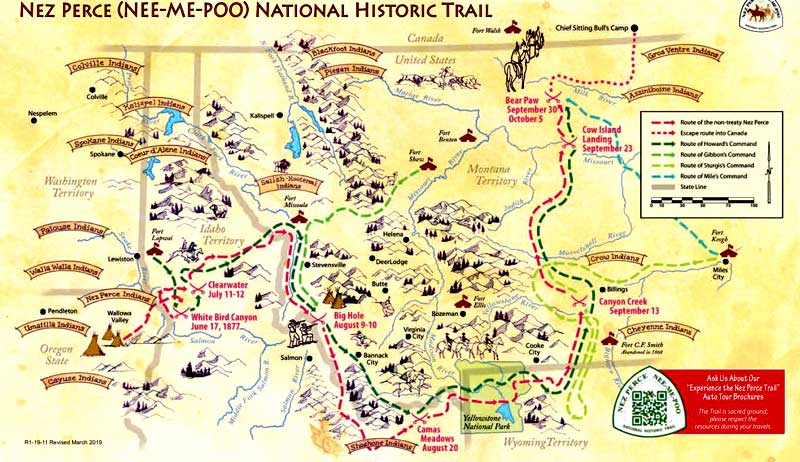

Facing overwhelming military might, the Nimiipuu made a fateful decision: they would flee. Their goal was to reach the protection of Sitting Bull’s Lakota people in Canada, nearly 1,200 miles away. Thus began one of the most extraordinary and tragic military campaigns in American history.

Approximately 750-800 Nimiipuu, including some 200 warriors and hundreds of women, children, and elderly, embarked on their desperate journey. They were pursued by several columns of the U.S. Army, led by General Howard, Colonel John Gibbon, and Colonel Samuel Sturgis.

The trail winds through some of the most rugged and breathtaking landscapes in the American West: the Wallowa Valley’s rolling hills, the daunting Salmon River Breaks, the dense forests of the Lolo Trail, the vastness of the Big Hole Valley, the towering peaks of Yellowstone, and the open plains of Montana. Each segment tells a piece of the story:

-

White Bird Canyon (June 17, 1877): The first major engagement. Against all odds, the Nimiipuu warriors, despite being outnumbered, decisively defeated Captain David Perry’s troops, suffering no fatalities while inflicting heavy casualties on the U.S. Army. This early victory fueled their resolve but also intensified the military’s pursuit.

-

The Lolo Trail and "Fort Fizz" (July 1877): The Nimiipuu skillfully traversed the treacherous Lolo Trail, an ancient trade route through the Bitterroot Mountains. At Lolo Pass, they encountered a hastily constructed barricade, "Fort Fizz," built by Montana volunteers. Through clever diplomacy and a feigned flanking maneuver, the Nimiipuu bypassed the fort without a shot being fired, earning grudging admiration from their pursuers.

-

The Battle of the Big Hole (August 9, 1877): This was the most devastating blow to the Nimiipuu. Colonel Gibbon’s troops launched a surprise dawn attack on their sleeping camp in the Big Hole Valley, Montana. The battle was a brutal massacre, with women, children, and the elderly among the first casualties. The Nimiipuu, though caught off guard, rallied fiercely, eventually driving Gibbon’s forces back. The cost, however, was immense: an estimated 60-90 Nez Perce, mostly non-combatants, were killed. Chief Joseph later remarked, "It was a massacre… many women and children were killed in their beds."

-

Yellowstone’s Surreal Interlude (August-September 1877): The exhausted Nimiipuu then pushed through the newly designated Yellowstone National Park, encountering awe-struck tourists and narrowly evading General Howard’s continued pursuit. This surreal passage through the park highlighted the stark contrast between their desperate flight and the burgeoning leisure of the American frontier.

-

Canyon Creek and Cow Island (September 1877): The Nimiipuu continued their strategic retreat, again demonstrating their military acumen at Canyon Creek against Colonel Sturgis’s cavalry. They then outsmarted soldiers guarding a supply depot at Cow Island, securing vital provisions.

The End of the Trail: Bear Paw and a Heartbreaking Surrender

By late September, the Nimiipuu were just 40 miles from the Canadian border, near the Bear Paw Mountains in northern Montana. They were exhausted, cold, and starving. On October 5, 1877, Colonel Nelson Miles’ fresh troops, having force-marched from Fort Keogh, launched a surprise attack.

The Nimiipuu quickly dug in, enduring a five-day siege in freezing conditions. The fighting was fierce, and several key chiefs, including Chief Looking Glass, were killed. With their people freezing and starving, and with the wounded unable to move, Chief Joseph made the agonizing decision to surrender.

His surrender speech, delivered through an interpreter, remains one of the most poignant and powerful statements in American history:

"Tell General Howard I know his heart. What he told me before, I have in my heart. I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed. Looking Glass is dead. Toohoolhoolzote is dead. The old men are all killed. It is the young men who say yes or no. He who led on the young men is dead. It is cold, and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food; no one knows where they are – perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children, and see how many of them I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs! I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever."

Approximately 430 Nimiipuu surrendered. A small number, including Chief White Bird, managed to escape to Canada. The promise of returning to their ancestral lands was broken. Instead, the surrendered Nez Perce were exiled to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma), a hot, humid environment alien to their mountain culture. Many died from disease and despair. Chief Joseph continued to advocate for his people until his death in 1904, never truly returning to the Wallowa Valley.

The Trail Today: A Living Legacy

In 1986, the Nez Perce National Historic Trail was established, managed by the U.S. Forest Service in partnership with the Nez Perce Tribe, other federal agencies, and state and local entities. It traverses parts of Oregon, Idaho, Montana, and Washington, marked by interpretive signs, visitor centers, and opportunities for hiking, horseback riding, and quiet reflection.

Today, walking segments of the Nee-Me-Poo Trail is more than just a scenic hike; it is a profound act of remembrance. It’s an opportunity to physically connect with the land that bore witness to such immense suffering and incredible resilience. You can stand at White Bird Canyon and imagine the initial clash, or trek through the dense Lolo Pass, marveling at the tactical genius of the Nimiipuu. At Big Hole, the silence is heavy with the ghosts of those who perished.

The trail serves as a vital educational tool, challenging simplistic narratives of westward expansion and illuminating the complex, often brutal, realities of the American frontier. It forces us to confront questions of justice, sovereignty, and the true cost of conflict. For the Nimiipuu people, the trail is a sacred path, a reminder of their ancestors’ sacrifice and an enduring symbol of their identity and survival.

As you stand on a windswept ridge overlooking vast plains, or trace the course of a river that carried the Nimiipuu’s hopes and fears, you can feel the echoes of their journey. The Nez Perce Historic Trail is not just a story of defeat, but of an indomitable spirit, a testament to a people who, despite unimaginable loss, refused to be broken. It calls us to remember, to learn, and to honor the enduring legacy of the Nimiipuu.