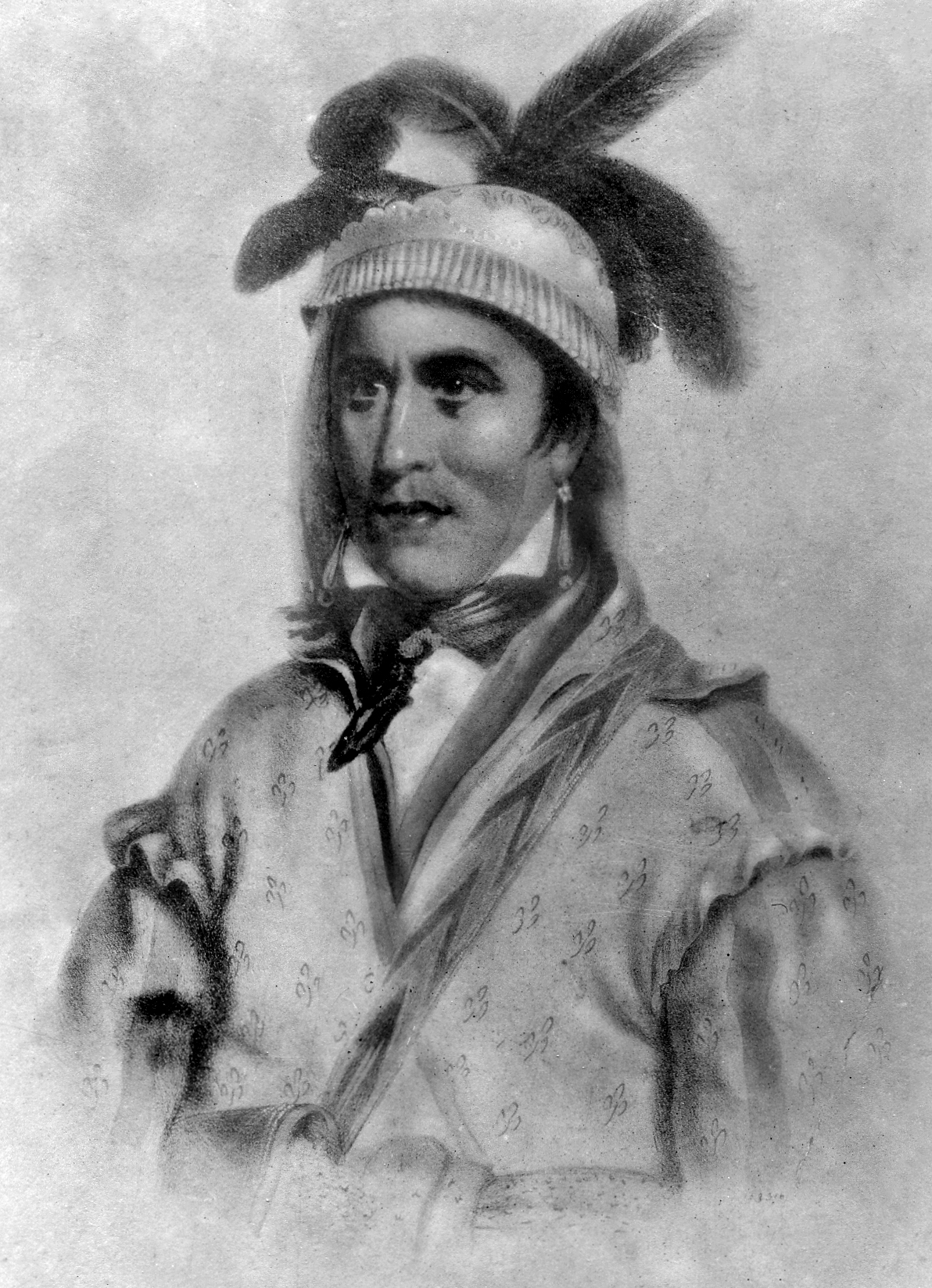

Opothleyahola: The Unyielding Spirit of the Creek Nation

In the vast, often turbulent tapestry of American history, certain threads remain stubbornly unspooled, their full pattern obscured by the passage of time or the selective focus of mainstream narratives. One such thread belongs to Opothleyahola, a towering figure of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation whose life spanned the most tumultuous decades of Native American existence in the 19th century. His story is one of unyielding leadership, profound loyalty, and unimaginable suffering, a testament to the resilience of a people caught between the relentless expansion of a young republic and the cataclysmic divisions of its Civil War.

Born around 1778, likely in what is now Alabama, Opothleyahola came of age during a period of intense pressure on the Muscogee Confederacy. He witnessed firsthand the erosion of ancestral lands, the betrayal of treaties, and the internal strife that plagued his people as they grappled with the encroaching tide of American settlers. A gifted orator and shrewd diplomat, he quickly rose through the ranks of the Upper Creeks, distinguished by his unwavering commitment to his nation’s sovereignty and cultural integrity. Unlike some of his contemporaries, such as William McIntosh who favored assimilation and land sales, Opothleyahola consistently advocated for traditional ways and fiercely resisted the cession of Muscogee territory.

His early political career was defined by a series of desperate negotiations with U.S. officials, including President Andrew Jackson, a man whose policies would inflict untold suffering on Native American nations. Opothleyahola understood the futility of armed resistance against the burgeoning military might of the United States, choosing instead the path of diplomacy and legal argument. He made multiple arduous journeys to Washington D.C., pleading the case of his people, arguing that the land belonged to the entire Creek Nation, not to a few chiefs who might be swayed by American incentives.

"The white man has come," he is said to have declared on one occasion, reflecting the grim reality, "and he wants our land. But this land is our mother; we cannot sell our mother."

Despite his tireless efforts, the inexorable pressure for land culminated in the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and the subsequent forced migration of the Muscogee people, among others, to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). Though he fought valiantly against the terms of removal treaties like the Treaty of Indian Springs (which was signed by McIntosh and led to his execution by the Creek National Council for treason), Opothleyahola ultimately had to lead his people on the infamous Trail of Tears in 1836. This forced exodus was a harrowing ordeal, marked by disease, starvation, and exposure, forever etched into the collective memory of the Muscogee people as a journey of profound loss.

Upon their arrival in Indian Territory, Opothleyahola dedicated himself to rebuilding the shattered fabric of the Creek Nation. He worked to establish new towns, revive traditional practices, and maintain a fragile peace amidst the lingering resentments of the removal. For nearly two decades, he presided over a period of relative stability and cultural resurgence, fostering agriculture, education, and self-governance within the confines of their new lands.

However, the peace was fleeting. As the 1850s drew to a close, the rumblings of the American Civil War began to echo even in the distant Indian Territory. The "Five Civilized Tribes" – the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole – found themselves in an impossible predicament. Their economies were intertwined with the South, many owned enslaved people, and their traditional territories bordered Confederate states. Yet, their treaties were with the United States government.

Opothleyahola, now an elder statesman, initially advocated for neutrality. He believed the conflict was a "white man’s war" and that Native nations should remain aloof, preserving their own strength and sovereignty. His position was rooted in a pragmatic understanding that siding with either faction would inevitably lead to further suffering for his already beleaguered people. He famously rejected overtures from Confederate Brigadier General Albert Pike, who sought to enlist the tribes into the Southern cause.

"We have our own troubles," Opothleyahola reportedly told a Confederate emissary, "and we want to be left alone."

But neutrality proved impossible. The Confederacy, viewing Indian Territory as strategically vital, exerted immense pressure. Pro-Confederate factions emerged within the tribes, notably led by Creek Chief Daniel N. McIntosh (son of the earlier William McIntosh) and Cherokee Stand Watie. As the lines hardened, Opothleyahola made a fateful decision: his loyalty, he declared, remained with the United States, based on the treaties that guaranteed his people’s land and protection. This was not necessarily an endorsement of Union ideology, but a pragmatic adherence to existing agreements and a rejection of the Southern cause which, in his view, offered no guarantees for his people’s future.

This decision splintered the Creek Nation, igniting a bitter internal conflict. In the autumn of 1861, as Confederate forces under Colonel Douglas H. Cooper began to consolidate control over Indian Territory, Opothleyahola, now in his early eighties, refused to submit. He gathered around him thousands of "Loyal Creeks," including men, women, children, and their African American allies (some enslaved, some free) who also sought refuge from Confederate rule. This diverse column, numbering as many as 9,000 souls, began a desperate exodus north, aiming for the safety of Union-held Kansas.

What followed was one of the most harrowing and least-known campaigns of the Civil War: the "Trail of Blood on the Snow." Cooper’s Confederate and pro-Confederate Native forces relentlessly pursued Opothleyahola’s column through the brutal winter of 1861-1862. Three major battles ensued:

-

The Battle of Round Mountain (November 19, 1861): The first engagement saw Opothleyahola’s forces, though poorly armed and supplied, hold their ground against Cooper’s initial attack, buying precious time for the main body of refugees to escape.

-

The Battle of Chusto-Talasah (December 9, 1861): A more intense clash, where Opothleyahola again skillfully deployed his warriors, inflicting heavy casualties on the Confederates before continuing their desperate retreat.

-

The Battle of Chustenahlah (December 26, 1861): This was the final, devastating encounter. Outnumbered and outgunned, Opothleyahola’s forces were overwhelmed. The battle turned into a rout, and the refugees scattered into the freezing wilderness, many freezing to death or succumbing to disease and starvation.

"The snow was red with blood," one survivor later recounted, describing the horrific aftermath of Chustenahlah. "We lost everything… but we held to our loyalty."

The survivors, decimated and utterly destitute, continued their torturous journey north, finally reaching Union lines in Kansas in early 1862. Thousands perished along the way from exposure, hunger, and battle wounds. Opothleyahola, despite his advanced age and the immense personal toll, continued to lead, tirelessly advocating for his people from the squalid refugee camps. He appealed to President Abraham Lincoln and other Union officials for aid, supplies, and recognition of his people’s unwavering loyalty.

Reports from Union officers who encountered the refugees paint a grim picture. Colonel William Weer wrote of them as "literally starving, many of them naked… a more deplorable picture of human suffering cannot be imagined." Yet, through it all, Opothleyahola maintained his dignity and his commitment to his people.

Chief Opothleyahola died in the refugee camp near Fort Belmont, Kansas, on March 22, 1863, at approximately 85 years old. He never saw his homeland again, nor did he witness the end of the war or the eventual return of his people to Indian Territory. His death marked the end of an era for the Creek Nation, a life defined by resistance to removal, steadfast loyalty to treaty obligations, and an epic struggle for survival against overwhelming odds.

Opothleyahola’s legacy is complex and profound. He represents the unyielding spirit of Native American self-determination in the face of relentless oppression. His story is a powerful reminder of the intricate and often tragic role Native nations played in the Civil War, and the immense sacrifices they made. He was not just a chief; he was a patriarch, a diplomat, a warrior, and a beacon of hope for his people, whose principled stand cost them dearly but preserved their honor and, ultimately, their cultural identity.

In an America that often overlooks the contributions and struggles of its Indigenous peoples, Opothleyahola’s name deserves to be recalled with reverence. His "Trail of Blood on the Snow" stands as a chilling testament to the human cost of conflict and a powerful symbol of endurance. He was an unyielding spirit, a leader who, even in his final years, chose the path of integrity over convenience, cementing his place as one of the most remarkable, yet tragically unsung, heroes of Native American history.