Certainly, here is an article focusing on the Penobscot Nation’s traditional fishing rights, written in a journalistic style and approximately 1,200 words.

The River’s Enduring Song: The Penobscot Nation’s Fight for Fishing Rights and Sovereignty

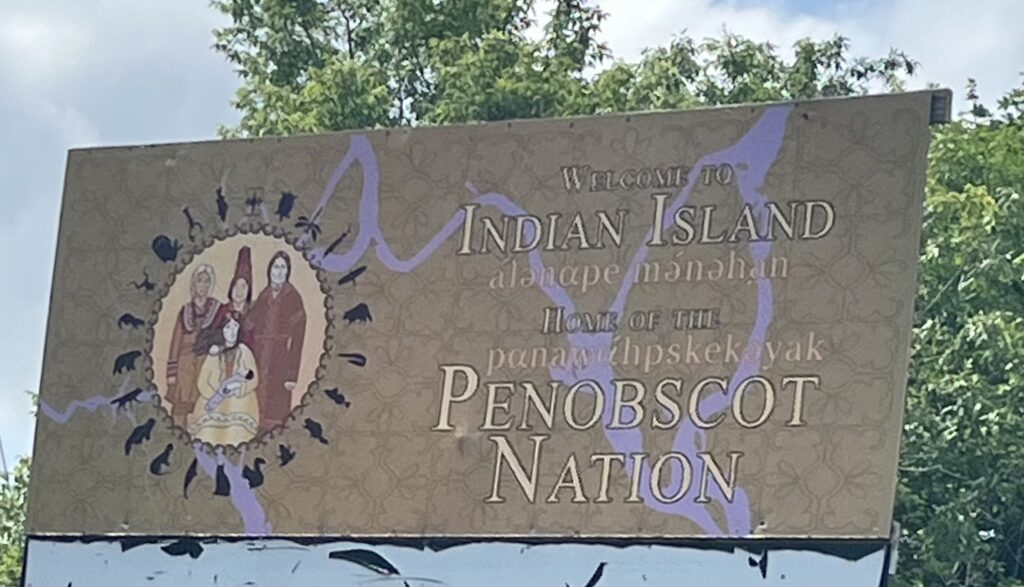

Along the Penobscot River, Maine’s largest waterway, the rhythm of life has for millennia been dictated by the ebb and flow of the tides and the migration of fish. For the Penobscot Nation, one of the five tribes of the Wabanaki Confederacy, this river – the "Penawapskewi" – is not merely a geographic feature; it is the very pulse of their identity, the source of sustenance, and the repository of generations of cultural knowledge. Their traditional fishing rights, however, are not just a matter of nets and canoes; they are a battleground for sovereignty, environmental justice, and the very definition of what it means to be Indigenous in modern America.

From the thunderous spring runs of alewives and Atlantic salmon to the elusive migration of eels and sturgeon, the river’s bounty shaped Penobscot society. Fishing was more than a means of survival; it was a spiritual practice, a communal event, and a cornerstone of their distinct way of life. Elders taught the young how to read the currents, identify the best fishing spots, and honor the fish that sustained them. This profound connection, etched into their very being, now stands in stark contrast to the legal and environmental challenges that threaten to sever it.

A History of Diminishment: Treaties and Industrialization

The Penobscot Nation’s aboriginal title to their vast ancestral territory was gradually extinguished through a series of treaties with the Commonwealth of Massachusetts (before Maine achieved statehood in 1820). These agreements, often coercive and poorly understood by the Nation, carved out a shrinking reservation on islands within the Penobscot River and along its banks. Crucially, the Nation maintained that these treaties protected their inherent rights to hunt, fish, and gather throughout their traditional territory, including the river itself.

The 19th and 20th centuries brought unprecedented change. Industrialization transformed the Penobscot River from a pristine ecosystem into an industrial highway. Log drives choked the river, and the proliferation of paper mills, pulp factories, and other industries upstream discharged immense quantities of toxic waste – dioxins, mercury, and other pollutants – directly into the waterway. Dams, built to power these industries and generate electricity, became insurmountable barriers for migrating fish, decimating populations of Atlantic salmon, once abundant enough to sustain entire communities.

By the late 20th century, the river was biologically devastated. Fish populations plummeted, and those that remained were often contaminated to the point of being unsafe for consumption. For the Penobscot, this was not merely an environmental crisis; it was a direct assault on their cultural survival. The river, once their "supermarket, church, and school," as many tribal members describe it, was becoming a toxic graveyard.

The Legal Quagmire: Defining "Reservation" and Jurisdiction

The fight for fishing rights in the Penobscot River is inextricably linked to a complex legal battle over the very definition of the Penobscot Nation’s reservation boundaries. At the heart of the dispute is whether the Nation’s reservation includes the main stem of the Penobscot River as it flows past their islands, or if their jurisdiction ends at the low-water mark along the riverbanks.

The Penobscot Nation argues that their 1790 and 1796 treaties with Massachusetts, which established their reservation, clearly intended to include the "islands and waters" of the river. They contend that their ancestors understood the river as an integrated system, not just the dry land. Furthermore, they assert that their inherent sovereign rights, never extinguished, include the authority to regulate fishing and water quality within their traditional territories.

The State of Maine, conversely, has long maintained that the Nation’s reservation consists only of the islands and the land bordering the river, arguing that the river’s main stem falls under state jurisdiction. This interpretation has profound implications: it dictates who has the authority to regulate fishing, enforce environmental standards, and even permit activities on the river.

This conflict escalated into a major lawsuit, Penobscot Nation v. Mills (later Maine v. Penobscot Nation), which wound its way through the federal courts. In 2015, a federal district court judge sided with the State, ruling that the Penobscot Nation’s reservation does not include the main stem of the river. This decision was a devastating blow to the Nation.

Chief Kirk Francis, Penobscot Nation’s Chief, expressed profound disappointment at the time, stating, "This decision is about more than fishing rights; it’s about our inherent sovereignty and our ability to protect our ancestral lands and waters for future generations." The Nation appealed the decision to the First Circuit Court of Appeals, which upheld the lower court’s ruling in 2017. The U.S. Supreme Court then declined to hear the case in 2018, effectively allowing the lower court’s decision to stand.

The legal defeat meant that the Penobscot Nation would continue to face challenges in regulating fishing by non-tribal members, protecting water quality, and exercising their full sovereign rights over the river that defines them. It forced them to rely on state regulations and enforcement, often perceived as inadequate or less stringent than what the Nation would implement.

Beyond the Courts: A Holistic Vision for Restoration

Despite the legal setbacks, the Penobscot Nation has never abandoned its commitment to the river. Their advocacy has been a driving force behind some of the most significant environmental restoration efforts in the United States.

One of the most remarkable achievements is the Penobscot River Restoration Project (PRRP). Initiated by a unique partnership between the Penobscot Nation, state and federal agencies, and conservation groups (including The Nature Conservancy and Atlantic Salmon Federation), this project aimed to restore native fish populations by removing key dams and improving fish passage. In 2012, the Great Works Dam was removed, followed by the Veazie Dam in 2013, opening up hundreds of miles of upstream habitat for migratory fish. A bypass channel was also built around the Howland Dam.

These efforts have yielded tangible results. "We’ve seen incredible returns of alewives, shad, and other species since the dams came out," notes a tribal biologist involved in monitoring. "It’s a testament to the river’s resilience and what can be achieved when people work together." While Atlantic salmon recovery remains a challenge due to other factors like ocean conditions and remaining dams, the project has been a beacon of hope.

However, the legal ruling limiting the Nation’s jurisdiction over the main stem continues to complicate these efforts. The Penobscot Nation remains a vigilant watchdog for the river’s health, advocating for stricter pollution controls, monitoring water quality, and pushing for cleanup of legacy industrial contaminants. Their traditional knowledge, passed down through generations, provides invaluable insights into the river’s ecosystem and its intricate balance.

The Cultural Imperative: Passing on the Legacy

For the Penobscot Nation, the fight for fishing rights is not merely about resource management; it’s about the survival of their culture. Fishing is a conduit for intergenerational knowledge transfer. Elders teach the young the ancient methods, the Penobscot language, and the spiritual protocols associated with harvesting from the river.

"When you teach a child how to fish in the river, you’re teaching them so much more," says a Penobscot elder. "You’re teaching them patience, respect for the natural world, responsibility, and their place in our history. You’re teaching them who they are."

The return of fish, even in limited numbers, rekindles hope and provides opportunities for these cultural practices to continue. The sight of a young Penobscot child learning to dip net for alewives, or respectfully releasing a salmon, is a powerful affirmation of resilience and continuity.

A Path Forward: Collaboration and Recognition

The Penobscot Nation’s struggle for its fishing rights and sovereignty over the Penobscot River reflects a broader national and global movement for Indigenous rights and environmental justice. It highlights the enduring legacy of colonialism, the ongoing challenges of treaty interpretation, and the critical need for tribal self-determination in managing ancestral lands and resources.

While the legal battle over the river’s main stem has been decided, the Penobscot Nation continues to assert its inherent sovereignty and to work collaboratively with state and federal partners where possible. They seek co-management agreements, stronger environmental protections, and a greater voice in decisions affecting the river.

The river’s song, though at times faint and strained by centuries of abuse and legal battles, continues to resonate in the hearts of the Penobscot people. Their fight is a testament to an unbreakable bond, a deep-rooted commitment to protecting their cultural heritage, and a vision for a future where the Penobscot River once again flows free and abundant, sustaining the people who have called it home since time immemorial. Their enduring presence on the river serves as a powerful reminder that true reconciliation requires not only recognizing past wrongs but also empowering Indigenous nations to reclaim their rightful place as stewards of their ancestral lands and waters.