Echoes from a Vanished World: Unearthing the Richness of Pre-Columbian America

Before the sails of Christopher Columbus touched the shores of the Bahamas in 1492, the Americas were far from an empty wilderness awaiting discovery. They were a vibrant tapestry of human civilization, a continent teeming with an astonishing diversity of cultures, languages, and societies that had flourished for millennia. From the frozen Arctic to the lush Amazon, and from the towering peaks of the Andes to the vast plains of North America, millions of people had built complex cities, developed sophisticated agricultural systems, crafted intricate art, and established profound spiritual traditions.

Yet, for centuries, the narrative of the "New World" has often overlooked, or deliberately diminished, the achievements of its original inhabitants. The term "Pre-Columbian" itself, while practical, subtly frames these civilizations as mere precursors to European arrival, rather than vibrant entities in their own right. It’s time to peel back the layers of misconception and truly appreciate the ingenuity, resilience, and grandeur of these forgotten empires and innovative communities.

The Urban Heartlands: Mesoamerica and the Andes

Nowhere was the complexity of Pre-Columbian societies more evident than in Mesoamerica (modern-day Mexico and Central America) and the Andean region of South America. These were cradles of monumental architecture, advanced astronomy, and highly organized social structures.

In Mesoamerica, the Olmec civilization, often dubbed the "mother culture," laid the groundwork for future societies as early as 1500 BCE. Known for their colossal basalt heads and early forms of writing, the Olmec influenced the subsequent rise of the Maya. The Maya, flourishing from around 250 CE to 900 CE, were not a unified empire but a network of independent city-states, each a marvel of urban planning. Cities like Tikal, Palenque, and Chichen Itza boasted towering pyramids, elaborate palaces, and complex ballcourts.

The Maya’s intellectual achievements were equally staggering. They developed a sophisticated hieroglyphic writing system, a highly accurate calendar that tracked celestial movements with astounding precision, and were among the first civilizations to independently develop the concept of zero. Their astronomical observatories, like El Caracol at Chichen Itza, allowed them to predict solar and lunar eclipses, guiding their agricultural and ceremonial cycles.

Further to the west, the Aztec Empire, though relatively young by 15th-century standards, was a dominant force. Its capital, Tenochtitlan, founded in 1325 CE on an island in Lake Texcoco, was a true wonder. With an estimated population of 200,000 to 300,000 at its peak, it rivaled or even surpassed the largest European cities of its time. Tenochtitlan was a marvel of engineering, featuring vast causeways, aqueducts, and an ingenious system of "chinampas" or floating gardens that allowed for highly productive agriculture. The Aztecs were master administrators, controlling a vast tribute empire through military might and a complex bureaucracy.

South America’s Andean civilizations were equally impressive, adapting to some of the world’s most challenging terrains. The Inca Empire, or Tawantinsuyu, was the largest empire in Pre-Columbian America, stretching over 2,500 miles along the spine of the Andes. What set the Inca apart was their unparalleled organizational genius. They built an extensive road system, the Qhapaq Ñan, spanning over 25,000 miles, connecting disparate regions and facilitating rapid communication and trade. They mastered sophisticated terraced farming, diverting water to cultivate crops like potatoes and quinoa at high altitudes.

The Inca lacked a written language but developed the quipu, a complex system of knotted strings used for record-keeping, census data, and even potentially narrative accounts. Sites like Machu Picchu, though often described as a "lost city," stand as testament to their architectural prowess and deep understanding of the landscape, seamlessly blending stone structures with the natural environment. Earlier Andean cultures like the Moche (known for their exquisite pottery and metallurgy) and the Nazca (creators of the enigmatic Nazca Lines) also showcased incredible artistic and engineering skills.

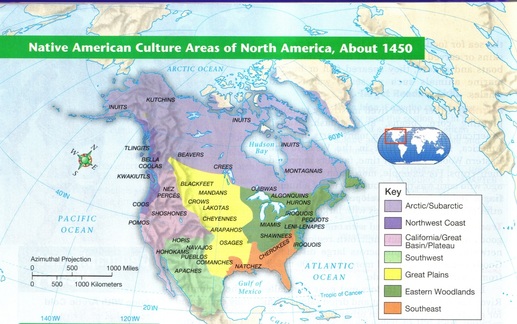

North America: Beyond the Great Empires

While Mesoamerica and the Andes often capture the spotlight, North America was home to an equally diverse array of sophisticated societies, each uniquely adapted to its environment.

In the Mississippi River Valley, the Mississippian culture flourished from around 800 CE to 1600 CE. Their most prominent city was Cahokia, located near modern-day St. Louis. At its peak around 1050 CE, Cahokia was larger than London at the time, with an estimated population of up to 20,000 people. Its central feature was Monks Mound, a massive earthen pyramid larger at its base than the Great Pyramid of Giza. Cahokia was a bustling urban center, a hub of trade, craft production, and a highly stratified society that built hundreds of mounds for ceremonial, residential, and burial purposes.

In the arid Southwest, the Ancestral Puebloans (often referred to by the Navajo term "Anasazi") developed remarkable architectural styles. From approximately 900 CE to 1300 CE, they constructed intricate cliff dwellings and multi-story "great houses" in places like Mesa Verde, Chaco Canyon, and Canyon de Chelly. Chaco Canyon, in particular, was a major ceremonial and trade center, featuring a network of precisely aligned roads connecting various great houses across hundreds of miles. These communities demonstrated ingenious methods of water management and sustainable agriculture in a challenging environment.

Along the Pacific Northwest coast, cultures like the Kwakiutl, Haida, and Tlingit developed societies rich in art, ritual, and social structure, centered around abundant marine resources. They are renowned for their intricate totem poles, monumental cedar canoes, and the potlatch, a complex ceremonial feast for distributing wealth and validating social status. Their understanding of resource management allowed for highly settled and prosperous communities without extensive agriculture.

Even in regions often perceived as less "developed," sophisticated systems were in place. The Iroquois Confederacy in the Northeast, for instance, established a democratic political system known as the Great Law of Peace, which some historians argue influenced the framers of the U.S. Constitution. On the Great Plains, before the introduction of the horse, various groups engaged in complex communal bison hunts and built earth lodges, demonstrating a deep knowledge of their environment and intricate social cooperation.

Common Threads and Lasting Legacies

Despite their vast geographical separation and distinct cultural expressions, many Pre-Columbian societies shared fundamental values and practices. A profound spiritual connection to the land and the natural world was almost universal. Oral traditions were paramount, serving as repositories of history, law, and wisdom. Communal well-being often trumped individualistic pursuits, and intricate kinship systems formed the backbone of social organization.

The achievements of these civilizations debunk the long-held myth of the Americas as an "empty" or "primitive" continent awaiting European enlightenment. They were innovators in agriculture, developing crops like maize, potatoes, and beans that now feed the world. They were master engineers, architects, and artists. They developed complex political systems, astronomical observatories, and sophisticated ecological management techniques.

The arrival of Europeans, however, brought not only new ideas but also devastating diseases and brutal conquest. Within a few generations, populations plummeted, empires crumbled, and countless languages, traditions, and knowledge systems were lost. Yet, the legacy of Pre-Columbian America endures. Indigenous peoples today are the living descendants of these remarkable societies, carrying forward traditions, languages, and worldviews that are deeply rooted in this rich past.

Understanding Pre-Columbian America is not just an academic exercise; it’s a crucial step in recognizing the full scope of human history and ingenuity. It challenges us to confront the biases embedded in our historical narratives and to appreciate the profound contributions of civilizations that flourished long before they were "discovered" – civilizations that shaped a continent and left an indelible mark on the human story. Their echoes still resonate, waiting for us to truly listen.