Ancient Roots, Future Harvests: The Enduring Wisdom of Pueblo Farming

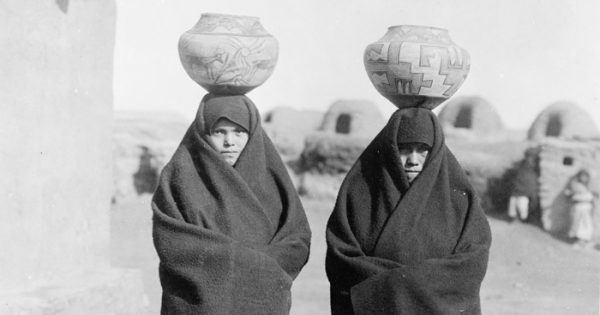

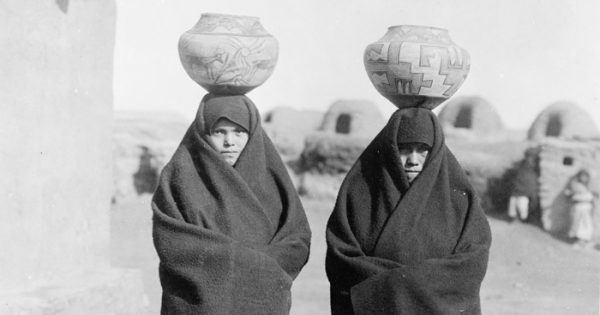

The American Southwest, a land of stark beauty and unforgiving aridity, has long tested the resilience of those who call it home. Against a backdrop of sun-baked mesas, deep canyons, and skies that stretch to eternity, generations of Pueblo peoples have not merely survived but thrived, cultivating life from a seemingly barren landscape. Their secret lies in an agricultural wisdom honed over millennia – a system of farming that is as much a spiritual practice as it is a means of sustenance, and one that holds profound lessons for a world grappling with climate change and food insecurity.

For more than 2,000 years, the ancestors of today’s Pueblo communities – including the Hopi, Zuni, Acoma, Taos, and numerous Rio Grande Pueblos – developed sophisticated dryland farming techniques that allowed them to grow staple crops like corn, beans, and squash in regions receiving as little as 7 to 16 inches of annual rainfall. This wasn’t merely about coaxing food from the earth; it was about understanding the earth, living in harmony with its rhythms, and fostering a deep, reciprocal relationship with the land that continues to define Pueblo identity.

“Our ancestors understood that the land is not just soil; it’s alive,” says a hypothetical Pueblo elder, her voice echoing generations of wisdom. “It breathes, it gives, and in return, we must respect it, listen to it, and care for it. Our farming is a conversation with the earth.”

The Sacred Trinity: Corn, Beans, and Squash

At the heart of Pueblo agriculture is the "Three Sisters" planting system: corn, beans, and squash. This ingenious polyculture is a testament to the Pueblo peoples’ profound ecological knowledge and remains a cornerstone of their traditional farms.

Corn, or maize, is the elder sister, providing the tall stalk for the beans to climb, lifting them towards the sun. The beans, in turn, are the middle sister, leguminous plants that fix nitrogen into the soil, naturally fertilizing the corn and squash. Finally, the squash, the youngest sister, spreads across the ground, its broad leaves shading the soil, conserving moisture, and deterring weeds. The prickly vines also protect the other plants from pests. This symbiotic relationship creates a self-sustaining ecosystem that maximizes yield and soil health without external inputs.

“The Three Sisters are more than just food; they are family,” explains a young Pueblo farmer, tending to a patch of vibrant green. “Each one helps the other, just like in our communities. It’s a lesson in cooperation that we see every day in our fields.”

Beyond their practical benefits, these crops hold immense spiritual significance. Corn, in particular, is central to Pueblo cosmology, seen as a sacred gift, a representation of life itself. Varieties of corn—blue, white, yellow, and red—are not just different colors; they embody different aspects of creation and are used in various ceremonies and culinary traditions.

Mastering Water: Ingenuity in Arid Lands

The true genius of Pueblo farming lies in its innovative water management strategies, designed to capture, conserve, and direct every precious drop of moisture. Unlike modern industrial agriculture that relies heavily on irrigation from distant sources, Pueblo methods are intrinsically tied to the immediate landscape.

Dry Farming: The most fundamental technique, dry farming, involves planting seeds deep into the soil to reach residual moisture and encourage deep root growth. Fields are often located in areas that receive natural runoff from mesas or hillsides, or in depressions where water naturally collects. Farmers meticulously observe the land, understanding microclimates and subtle shifts in topography that indicate where water will gather.

Waffle Gardens: A visually striking and highly effective method is the "waffle garden." These small, raised beds are surrounded by earthen berms, creating a grid-like pattern resembling a waffle. Each square acts as a miniature reservoir, trapping rainwater and preventing runoff. This allows moisture to slowly percolate down to the plant roots, maximizing water retention in the immediate vicinity of the crops. This method is particularly effective for smaller, intensively managed plots near homes.

Akchin Farming (Floodplain Agriculture): For larger fields, particularly in areas near ephemeral washes or arroyos, Pueblo farmers utilize "akchin" or floodplain agriculture. This involves diverting seasonal floodwaters from washes onto fields using simple rock dams or earthen structures. The floodwaters deposit nutrient-rich silt, naturally fertilizing the land, while also deeply saturating the soil for the growing season. This method is a masterclass in passive irrigation, relying entirely on natural hydrological processes.

Terracing: In hilly or sloping terrain, ancient Pueblo farmers constructed intricate terraces. These steps not only created level planting areas but also slowed down water runoff, allowing it to soak into the soil rather than eroding it away. The remnants of these ancient terraces can still be seen etched into the landscape of places like Mesa Verde and Chaco Canyon, testaments to a sophisticated understanding of hydrology and engineering.

The Guardians of Seeds: Biodiversity and Adaptation

Another critical component of Pueblo agricultural resilience is seed saving. For millennia, Pueblo farmers have carefully selected and preserved seeds from their strongest, most productive, and most drought-resistant plants. This continuous process of selection has resulted in a vast diversity of heirloom varieties, each uniquely adapted to specific local conditions – whether it’s a particular soil type, elevation, or rainfall pattern.

“Our seeds are our history, our future,” a community leader might emphasize. “They carry the memory of our ancestors, the strength of our land. To lose our seeds is to lose a part of ourselves.”

This genetic diversity is a powerful buffer against crop failure. If one variety struggles in a given year due to unusual weather, another might thrive. In an era of increasing climate variability and the homogenization of global agriculture, the Pueblo commitment to seed diversity offers a vital blueprint for food security and ecosystem health. It stands in stark contrast to industrial agriculture’s reliance on a few genetically uniform, chemically dependent varieties.

More Than Sustenance: A Cultural and Spiritual Tapestry

Pueblo farming is not merely an economic activity; it is deeply interwoven with their cultural identity, spiritual beliefs, and social structures. The annual farming cycle dictates many ceremonies, dances, and rituals, from planting blessings to harvest celebrations. These practices reinforce the community’s connection to the land, to each other, and to the spiritual world.

Children learn about farming from a young age, not just through instruction but by active participation. They learn the names of the plants, the feel of the soil, the rhythm of the seasons. This intergenerational transfer of knowledge ensures the continuity of these vital traditions.

“When we plant, we are praying. When we harvest, we are giving thanks,” a Pueblo elder might explain. “Every step is a ceremony. It reminds us that we are part of something much larger than ourselves.”

Challenges and Revival

Despite its enduring wisdom, Pueblo traditional farming has faced immense challenges. Colonialism, forced assimilation policies, and the imposition of Western agricultural practices disrupted traditional ways of life. The lure of wage labor, the decline in access to traditional lands, and the availability of cheaper, mass-produced food have also led to a decrease in active farming among some communities. Climate change, too, presents new obstacles, with more extreme droughts and unpredictable weather patterns threatening even the most resilient crops.

However, there is a powerful resurgence of interest and activity in traditional farming methods across Pueblo lands. Younger generations, often educated in Western universities, are returning home with a renewed appreciation for their heritage. They are combining ancestral knowledge with contemporary science to innovate and adapt. Community gardens are flourishing, seed banks are being revitalized, and intergenerational learning programs are connecting elders with youth.

Projects focusing on indigenous food sovereignty are empowering communities to reclaim control over their food systems, promoting healthier diets, and strengthening cultural bonds. They are demonstrating that traditional farming is not a relic of the past but a dynamic, evolving system with profound relevance for the future.

Lessons for a Changing World

The enduring wisdom of Pueblo traditional farming offers critical lessons for a world grappling with the existential threats of climate change, resource depletion, and food insecurity.

- Resilience and Adaptability: Pueblo farming teaches us that survival in harsh environments requires deep understanding of natural systems and the flexibility to adapt.

- Sustainability: These methods inherently promote soil health, water conservation, and biodiversity, demonstrating how to grow food without depleting the environment.

- Community and Connection: It underscores the importance of communal effort, intergenerational knowledge transfer, and a spiritual relationship with the land.

- Food Sovereignty: It highlights the value of local food systems, diverse crop varieties, and community control over food production.

In a world increasingly seeking sustainable solutions, the ancient fields of the Pueblo peoples offer more than just a glimpse into the past. They provide a living, breathing model for a future where humanity lives in balance with the earth, where food is grown with respect, and where the wisdom of ancestors continues to nourish generations to come. Their enduring harvest is not just of corn, beans, and squash, but of hope, resilience, and a profound connection to the land itself.