Woven Narratives: Unraveling the Language of Salish Basketry Patterns

More than mere containers, the traditional baskets of the Salish peoples are profound repositories of history, culture, and spirit. From the rugged coastlines of British Columbia and Washington State to the interior plateaus, Salish basketry represents an enduring art form, its intricate patterns serving as a visual language that narrates stories of the land, its creatures, and the wisdom of generations. These patterns are not just decorative; they are symbols, maps, and prayers, woven into the very fabric of Indigenous identity.

For thousands of years, long before European contact, Salish communities developed sophisticated basketry traditions, deeply intertwined with their subsistence, spiritual beliefs, and social structures. The vast Salish linguistic family encompasses numerous distinct nations—Coast Salish groups like the Squamish, Lummi, Sto:lo, and Tsleil-Waututh, and Interior Salish groups such as the Okanagan, Secwepemc, and Nlaka’pamux—each with their unique dialect of this woven language, yet sharing a common reverence for the materials and the knowledge passed down through generations.

The Foundation: Materials and Techniques

The foundation of Salish basketry lies in an intimate understanding of the natural world. Master weavers possessed profound knowledge of plant cycles, harvesting times, and preparation techniques. The primary materials varied by region, reflecting the local ecology:

- Cedar Root (Thuja plicata): Predominantly used by Coast Salish peoples, the inner bark and roots of the Western Red Cedar were prized for their strength, flexibility, and resistance to water. Roots were carefully dug, peeled, split, and coiled tightly to create sturdy, watertight baskets often used for cooking (by dropping hot rocks inside), storage, and clam digging.

- Cedar Bark: Both inner and outer bark were processed for twining and plaiting, creating softer, more flexible items like mats, hats, and open-weave burden baskets.

- Bear Grass (Xerophyllum tenax): Highly valued by Interior Salish weavers, particularly for its strength and pale, lustrous quality. It was often used for overlay designs on coiled baskets, creating striking patterns against a darker base.

- Cherry Bark (Prunus emarginata): Harvested in thin strips, it provided a rich reddish-brown contrast for patterns.

- Spruce Root (Picea sitchensis): Used similarly to cedar root in some coastal areas.

- Other Fibers: Cattail, bulrush, nettle, and dogbane fibers were also incorporated for specific purposes or decorative elements.

The two primary construction techniques, coiling and twining, each lent themselves to different types of baskets and influenced the expression of patterns.

Coiling: This method involves spiraling a bundle of foundation material (like cedar root or grass) and stitching it together with another, finer material. It creates rigid, durable baskets that are often round or oval. The patterns in coiled baskets are typically created by varying the color of the stitching material or by incorporating different materials as an overlay.

Twining: This technique involves two weft strands twisted around a rigid warp. It produces more flexible baskets, often with a tighter, less porous weave. Patterns are formed by manipulating the weft strands, creating distinct geometric or pictorial designs.

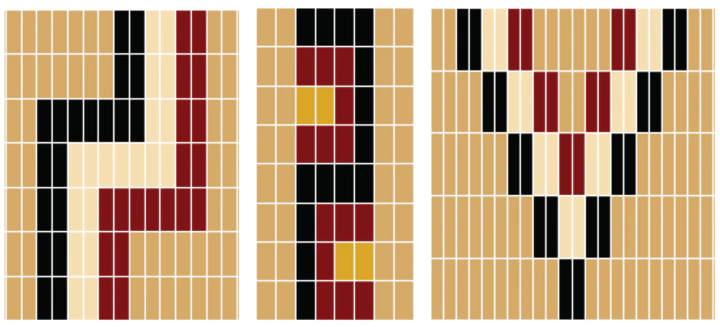

The Visual Dialect: Decoding the Patterns

The patterns woven into Salish baskets are far from random. They are a complex visual language, rich with symbolism, historical narratives, and spiritual meaning. While specific interpretations might vary slightly between nations and even individual families, common themes and motifs emerge.

"Every stitch, every motif, tells a story," explains Dr. Lena Strong, a fictional cultural historian specializing in Northwest Coast Indigenous arts. "These aren’t just designs; they’re memories, prophecies, lessons passed down through the hands of our ancestors. They connect us to the land, to our animal relatives, and to the spirits that guide us."

Geometric Patterns: These are perhaps the most common and versatile. Their abstract nature allows for multiple layers of meaning.

- Triangles and Zigzags: Often represent mountains, peaks, valleys, or the ripples of water. "The ‘mountain peak’ pattern might signify strength and resilience, or a specific sacred site known to the weaver’s family," notes Strong. Zigzags can also denote lightning, the path of a river, or the movement of a snake.

- Diamonds and Squares: Can symbolize eyes (often animal eyes, reflecting keen observation), stars, or the four directions. The "eye" pattern, for instance, might represent the watchful presence of an ancestor or a protective spirit.

- Chevrons and Parallel Lines: Can depict trails, pathways, or the flowing movement of water.

- Checkerboard or Alternating Blocks: Often represent cultivated fields, fishing nets, or the scales of a fish, particularly salmon, which is central to Salish life.

Zoomorphic Patterns (Animal Motifs): Animals hold immense significance in Salish cosmology, often appearing as spirit helpers, clan crests, or characters in origin stories. While often stylized rather than strictly realistic, these animal forms are immediately recognizable to those who understand the visual code.

- Salmon: A cornerstone of Salish diet and culture, salmon motifs (often depicted as stylized heads, tails, or scales) represent abundance, sustenance, and the cyclical nature of life.

- Deer Tracks or Elk Tracks: Symbolize the hunt, connection to the forest, and the respectful relationship with game animals.

- Wolf or Bear Paws: Represent strength, wisdom, and protection.

- Birds (e.g., Flying Geese, Thunderbird): Can signify journeys, freedom, or spiritual power. The Thunderbird, a powerful mythical creature, is a common motif across many Indigenous cultures of the Northwest Coast, symbolizing thunder, lightning, and rain, and often appearing in a highly stylized, abstract form.

- Water Creatures: Fish, frogs, or stylized waves often reflect the deep connection to rivers, lakes, and the ocean.

Anthropomorphic Patterns (Human Forms): Less common but equally powerful, these patterns depict human figures or spirit beings. They can represent ancestors, shamans, or figures from creation stories, often conveying messages about community, leadership, or spiritual journeys. A series of interconnected figures might symbolize community unity or a lineage.

Narrative Patterns: Some patterns are more complex, combining several elements to tell a specific story or commemorate an event. A basket might feature a series of mountain peaks, a winding river, and a salmon motif, collectively depicting a particular fishing expedition or a sacred journey. These narrative elements often make a basket a unique historical document.

Cultural Significance Beyond Utility

The significance of Salish basketry patterns extends far beyond their aesthetic appeal or functional purpose.

- Identity and Kinship: Patterns could identify a weaver’s nation, family lineage, or even specific village. "You could tell where someone was from, what river their family fished, just by looking at the patterns on their basket," says Clara Whitefeather, a contemporary Lummi master weaver. "It was like a passport, a family crest, all in one."

- Teaching Tools: Baskets served as pedagogical instruments. Children learned about their environment, cultural stories, and traditional practices by observing and assisting in the weaving process. The patterns themselves were visual mnemonics for oral traditions.

- Spiritual Connection: The act of gathering materials involved prayers and offerings, acknowledging the spirit of the plants. The weaving process was often meditative, a form of spiritual practice. The patterns themselves could invoke protection, blessings, or express gratitude.

- Trade and Diplomacy: Baskets were valuable trade items, facilitating economic exchange and strengthening alliances between nations. The quality and intricacy of the patterns often reflected the status and skill of the weaver and her community.

Challenges and Resilience

The arrival of European settlers brought devastating changes that severely impacted Salish basketry traditions. Colonial policies, including the residential school system, forcibly removed children from their families, disrupting the intergenerational transfer of knowledge crucial for weaving. Land dispossession limited access to traditional harvesting grounds for materials. The introduction of manufactured goods also reduced the immediate utilitarian need for baskets.

Despite these immense pressures, the tradition persevered, often in secret, held alive by resilient elders who refused to let their heritage die. "My grandmother used to hide her baskets when the Indian Agent came," Whitefeather recalls. "She kept the knowledge alive in her heart, in her hands, and eventually, she passed it to me."

The Revival and Future of Woven Narratives

In recent decades, there has been a powerful resurgence in Salish basketry, driven by a deep commitment to cultural revitalization. Master weavers, often elders who learned from their grandmothers, are now diligently teaching younger generations. Cultural centers, museums, and educational institutions are playing a vital role in supporting this revival through workshops, apprenticeships, and exhibitions.

Contemporary Salish weavers are not merely replicating old patterns; they are engaging in a dynamic dialogue with tradition. While honoring ancestral designs, many are also innovating, incorporating new materials, colors, and personal narratives into their work, ensuring the art form remains a living, evolving expression.

The process of weaving today remains much as it was centuries ago: arduous, time-consuming, and deeply meditative. It requires immense patience, skill, and a profound connection to the land and the materials. "When I’m weaving, I feel my ancestors’ hands guiding mine," says Whitefeather. "Each pattern I lay down is a conversation with the past, a prayer for the future."

The patterns of Salish traditional basketry are more than just beautiful designs. They are the indelible script of a vibrant culture, a testament to the resilience of a people, and a continuous affirmation of their deep connection to the land and their heritage. As new generations pick up the cedar roots and bear grass, they are not just learning a craft; they are reclaiming a language, weaving new narratives, and ensuring that the stories of the Salish people continue to be told, one intricate stitch at a time.