Echoes in Cedar: The Enduring Legacy of Salish Traditional Carving

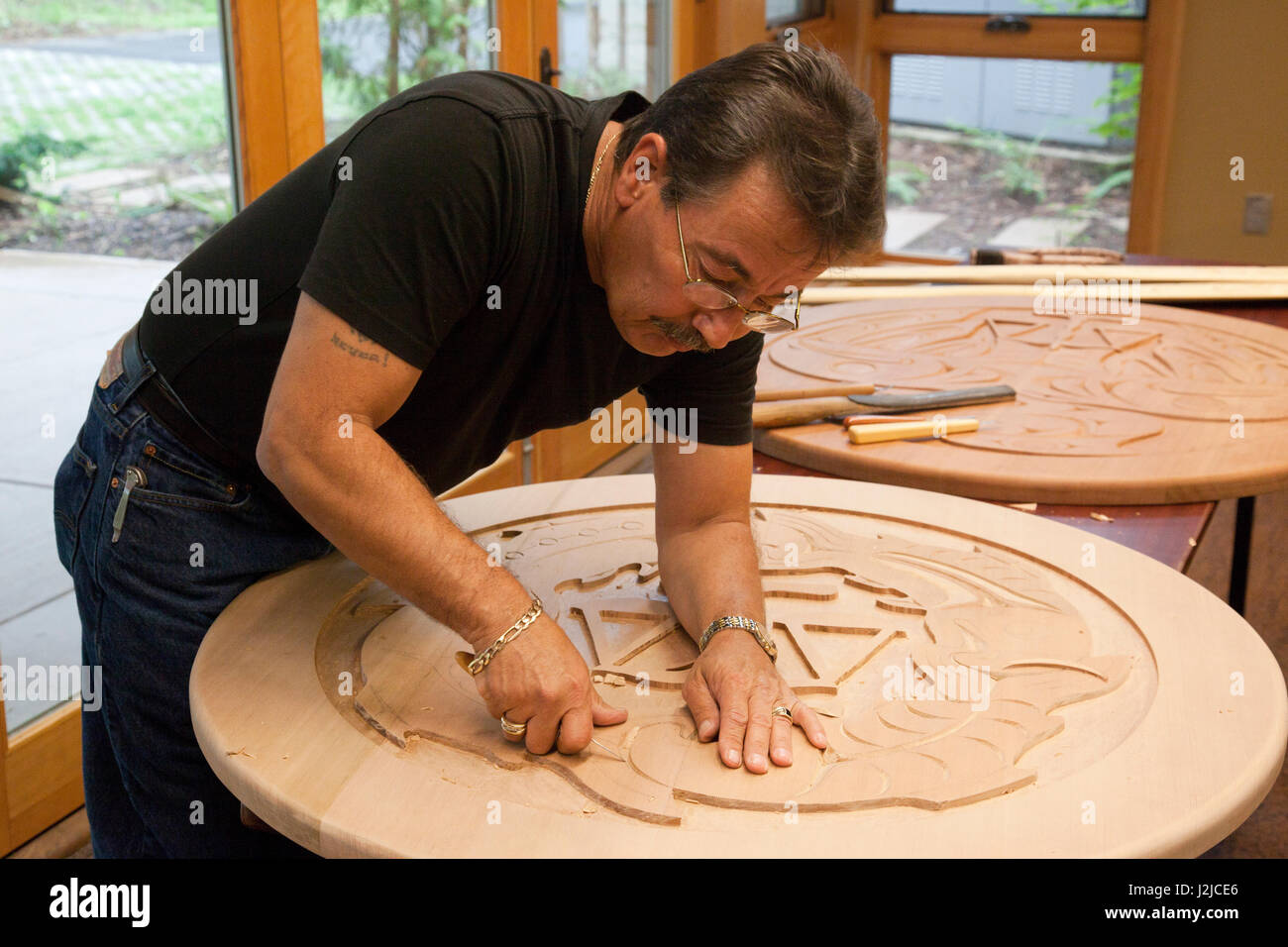

The air in the workshop hums with the soft rasp of an adze, the rhythmic tap of a chisel, and the distinctive, resinous scent of red cedar. Sunlight filters through the high windows, illuminating dust motes dancing around the focused figures bent over their work. Here, on the traditional territories of the Coast Salish peoples, the ancient art of carving is not merely a craft; it is a living language, a spiritual conduit, and a vibrant declaration of cultural resilience.

For thousands of years, long before European contact, Salish artists transformed the abundant cedar of the Pacific Northwest into objects of profound beauty and utility. From monumental house posts that bore the weight of community narratives to intricate spindle whorls vital for weaving, and from powerful ceremonial masks to sleek, ocean-going canoes, carving was interwoven with every aspect of Salish life. These weren’t just decorative items; they were mnemonic devices, spiritual tools, and tangible expressions of identity, history, and connection to the land and its myriad inhabitants.

"Our carvings tell our stories, our history, our laws," explains Xyolhmet, a revered elder and master carver from the Squamish Nation. "They are our books. When you look at a pole or a mask, you are seeing generations of knowledge, power, and connection." This sentiment encapsulates the deep reverence for a tradition that nearly vanished but is now experiencing a powerful resurgence.

A Distinctive Aesthetic: Beyond the Totem Pole

When many people think of Northwest Coast Native art, the towering, highly stylized totem poles of the Haida, Tsimshian, and Kwakwaka’wakw nations often come to mind. While these are magnificent examples of Indigenous art, Coast Salish carving possesses a distinct aesthetic, less focused on the rigid "formline" of their northern neighbors and more on a curvilinear, sculptural approach that emphasizes flowing lines, humanistic forms, and a profound sense of the material itself.

Coast Salish carvings often feature ovoid shapes, U-forms, and trigons, creating a dynamic interplay of positive and negative space. Figures, whether human, animal, or transformational, are often rendered with a remarkable sense of naturalism, yet imbued with a spiritual intensity. Eyes are frequently large and expressive, suggesting wisdom and a deep connection to the spirit world. Animals like the raven, wolf, bear, salmon, and thunderbird are common motifs, each carrying specific meanings and often representing clan lineages or spiritual guardians. Transformation – the ability of a being to shift from human to animal form and vice-versa – is a recurring theme, reflecting the fluidity of the spirit world and the interconnectedness of all life.

Materials are paramount, with Western Red Cedar (Thuja plicata) being the cornerstone. Its strength, lightness, and resistance to rot, combined with its straight grain and workability, made it the ideal medium. Yellow Cedar (Callitropsis nootkatensis) was also used for its finer grain and distinctive scent. Traditional tools included various forms of adzes (D-adze, elbow adze), chisels, and knives, often with blades fashioned from shell, bone, or stone before the advent of metal tools. Modern carvers often blend traditional tools with contemporary ones, but the spirit of the ancient methods remains. "You learn to listen to the wood," says a young apprentice, carefully shaving a curl from a mask with a bent knife. "It tells you where it wants to go."

A History of Suppression and Resilience

The arrival of European settlers brought profound disruption to Salish societies, and with it, a devastating assault on their cultural practices. Policies of assimilation, including the infamous Potlatch Ban (1884-1951) in Canada, criminalized traditional ceremonies where carved objects played a central role. Children were forcibly removed to residential schools, where their languages, beliefs, and artistic traditions were systematically suppressed. Many invaluable pieces of art were confiscated, sold, or destroyed, ending up in museums and private collections around the world.

This period led to a dramatic decline in the practice of carving. Generations grew up without direct access to the knowledge and skills that had been passed down orally and through apprenticeship for millennia. The vibrant artistic lineage was fractured, but it was never entirely broken. Despite the immense pressure, some families and individuals continued to carve in secret, preserving fragments of the tradition against overwhelming odds.

The mid-20th century saw the beginnings of a cultural resurgence. Artists like Susan Point (Musqueam), Robert Davidson (Haida), and Bill Reid (Haida) played pivotal roles in bringing Northwest Coast art back into public consciousness, inspiring a new generation. While much of the initial revival focused on the more widely recognized northern styles, Coast Salish artists began to reclaim and re-assert their own distinct visual language. This was a challenging process, as many traditional forms and designs had been lost or scattered. Artists had to pore over museum collections, consult elders, and often piece together fragmented knowledge to reconstruct their artistic heritage.

The Modern Carver: Guardians of a Living Tradition

Today, the landscape of Salish carving is vibrant and dynamic. Master carvers, often drawing inspiration from ancestral pieces, are training apprentices in community workshops, passing on not just techniques but also the deep cultural understanding that underpins the art. These apprenticeships are rigorous, demanding years of dedication and a profound respect for the materials and the ancestors who first worked them.

"It’s not just about learning to cut wood," explains Rose Point, a Musqueam artist following in the footsteps of her renowned mother, Susan Point. "It’s about learning our history, our spiritual connection, our responsibility to carry this forward for the next generation. Each piece is a prayer, a connection."

Modern Salish carvers navigate a complex world. They are often ambassadors for their culture, educating the public about the richness and diversity of Indigenous art. Their work graces public spaces, galleries, and private collections worldwide. The economic realities are challenging; carving is a physically demanding and time-consuming profession, and ensuring fair compensation for culturally significant work is an ongoing struggle. Many artists also grapple with issues of cultural appropriation, where non-Indigenous individuals or companies reproduce Indigenous designs without permission or understanding.

Yet, the passion endures. The act of carving itself is often described as a spiritual journey, a dialogue between the artist, the wood, and the ancestors. The process is slow and deliberate, requiring patience and a deep connection to the material. From the initial blessing of the cedar log to the final application of natural pigments, every step is imbued with meaning.

The Future: Carving a Path Forward

The future of Salish traditional carving lies in the hands of the youth. Programs in schools and community centers are introducing young people to the art form, fostering a sense of pride and cultural identity. The availability of resources – from sustainably harvested cedar to access to training – is crucial for the continued flourishing of the art.

Moreover, there is a growing movement towards repatriation, where Indigenous communities are advocating for the return of ancestral artworks from museums and private collections. The return of these pieces is not just about ownership; it’s about reconnecting communities with their tangible heritage, allowing them to study, learn from, and draw inspiration directly from the works of their ancestors.

The legacy of Salish traditional carving is one of extraordinary resilience and profound beauty. It is a testament to the enduring spirit of a people who, despite immense adversity, have kept their cultural flame burning brightly. As the scent of cedar continues to waft from workshops across the Coast Salish territories, each new cut, each new form emerging from the wood, is not just a piece of art; it is a powerful echo of the past, a vibrant expression of the present, and a hopeful declaration for the future. It is the language of the land, spoken through the hands of its people, ensuring that the stories carved in cedar will continue to resonate for generations to come.