Echoes of Resilience: The Vital Quest to Revitalize the Seminole Language

The words are soft, a rhythmic murmur of guttural sounds and flowing vowels, each syllable carrying centuries of history, culture, and identity. In a brightly lit classroom, whether physical or virtual, a group of learners leans forward, their expressions a mix of concentration and eagerness. They are not merely learning a new vocabulary; they are reclaiming a legacy. This is the heart of the Seminole language revitalization effort, a profound and urgent mission to safeguard the linguistic soul of a nation.

For the Seminole Tribe of Florida and the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, language is not just a tool for communication; it is the very bedrock of their sovereignty, their spiritual connection to their ancestors, and their unique worldview. Yet, like many Indigenous languages across the globe, the Seminole languages have faced existential threats, primarily due to historical policies of forced assimilation, including the traumatic era of boarding schools where children were punished for speaking their native tongues.

Today, the number of fluent, first-language speakers of the two main Seminole languages – Mikasuki (often spoken by the Florida Seminoles and Miccosukee Tribe) and Maskókî (or Seminole Creek, prevalent among the Oklahoma Seminoles and some Florida bands) – has dwindled significantly. Estimates vary, but many tribal leaders acknowledge that the majority of fluent speakers are elders, and without concerted intervention, the languages risk falling silent within a generation.

This stark reality has ignited a fierce determination among the Seminole people to reverse the tide. Across reservations and through digital platforms, a vibrant movement is taking root, driven by dedicated elders, passionate educators, and a rising generation hungry to reconnect with their linguistic heritage.

The Classroom as a Sacred Space

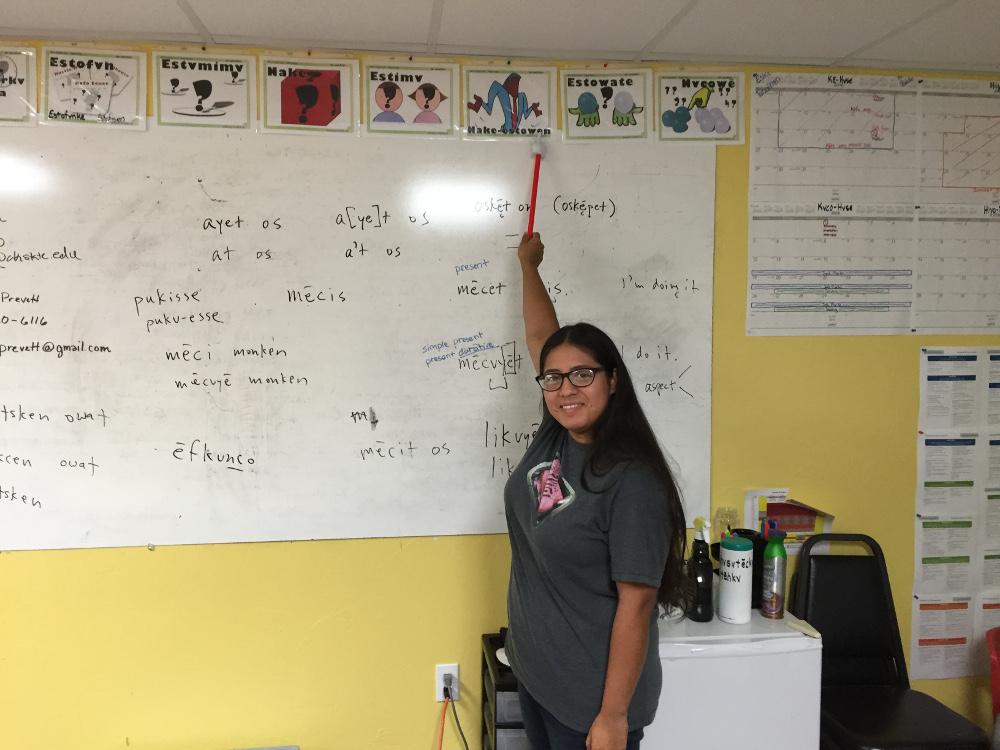

At the forefront of this movement are the Seminole language classes themselves. These are not your typical foreign language courses. They are immersive, culturally rich experiences designed to transmit not just words, but the spirit embedded within them.

"When you learn our language, you’re learning our history, our ceremonies, our way of thinking," explains a seasoned Seminole language instructor, a fluent Maskókî speaker whose voice carries the weight of generations. "Every word has a story, every phrase a connection to our land and our ancestors. It’s more than just grammar; it’s a worldview."

Classes are offered in various formats to accommodate the diverse needs of tribal members. On the Seminole reservations in Florida – Hollywood, Big Cypress, Brighton, and Immokalee – in-person classes are held in tribal community centers, schools, and cultural sites. These often begin with traditional prayers or songs, setting a respectful and culturally appropriate tone. Beginners might start with basic greetings, family terms, and simple commands, gradually building up to more complex sentence structures and conversational fluency.

For tribal members who live off-reservation or have demanding schedules, online classes have become an indispensable tool. Platforms like Zoom have allowed individuals from across the country to participate, bridging geographical divides and fostering a broader sense of community among learners. These virtual classrooms are often just as lively and interactive as their physical counterparts, with instructors utilizing digital flashcards, audio clips, and shared screens to teach pronunciation and vocabulary.

"The online classes have been a lifesaver for me," says Sarah Osceola, a young Seminole mother living in Orlando, who dedicates her evenings to learning Mikasuki. "I grew up hearing my grandmother speak it, but I never learned fluently myself. Now, I can connect with my heritage in a way I never thought possible, and I hope to pass it on to my children."

Guardians of the Tongue: The Role of Elders

Central to the success of these programs are the elders – the invaluable first-language speakers who serve as living dictionaries and cultural repositories. Many of them never had the opportunity to learn English in their youth, or learned it later in life, making their native tongue their primary mode of expression. They are the "Guardians of the Tongue," and their participation is voluntary, driven by a profound sense of responsibility to their people.

Often, these elders serve as co-teachers, working alongside younger, formally trained educators who may have developed pedagogical methods for language instruction. This intergenerational collaboration is vital: the elders provide authentic pronunciation, idiomatic expressions, and cultural context, while the educators structure lessons and create accessible learning materials.

"Our elders hold the key," says a program coordinator for the Seminole Tribe of Florida’s Language Department. "They are the wisdom keepers. Our job is to create pathways for that knowledge to be shared, respectfully and effectively, with the next generations."

The teaching methods often go beyond rote memorization. Immersion techniques, where learners are encouraged to speak only the target language for set periods, are increasingly being employed. Storytelling, a cornerstone of Seminole culture, is also integrated into lessons, allowing learners to hear the language in a narrative context and connect with traditional tales. Traditional songs, chants, and even culinary lessons (where ingredients and cooking methods are discussed in Mikasuki or Maskókî) also serve as powerful vehicles for language acquisition.

Overcoming Challenges and Forging New Paths

Despite the passion and dedication, the language revitalization effort faces significant hurdles. The sheer number of fluent speakers is a constant concern. Many elders are aging, and their passing represents an irreplaceable loss of linguistic and cultural knowledge.

Another challenge is competing with the dominant influence of English. In an increasingly globalized world, English is the language of commerce, education, and mainstream media, often making it difficult for tribal languages to compete for attention and time, particularly among younger generations. Resources, while improving, can also be a limiting factor, affecting everything from curriculum development to the recruitment and training of new instructors.

However, the Seminole people are innovators, and they are leveraging modern technology to overcome these obstacles. Tribal governments have invested in creating digital resources, including language apps for smartphones and tablets, online dictionaries, and interactive learning modules. These tools allow learners to practice outside of class, reinforce lessons, and access pronunciation guides at their convenience. Some apps even incorporate gamification elements to make learning more engaging for younger users.

Partnerships are also proving crucial. The Seminole Tribe of Florida, for example, has collaborated with universities to develop advanced language programs and research initiatives aimed at documenting and preserving the languages. Linguists and anthropologists work with tribal members to create comprehensive dictionaries, grammar guides, and archives of spoken language, ensuring that future generations will have access to these invaluable resources.

Furthermore, the language revitalization effort is not confined to formal classrooms. Community events, cultural festivals, and family gatherings are increasingly becoming spaces where the languages are encouraged and celebrated. Some families have even committed to creating "language nests" or "language homes" where only the Seminole language is spoken, particularly to young children, aiming to raise the next generation of first-language speakers.

The Profound Impact: Reclaiming Identity and Sovereignty

The impact of these language classes extends far beyond mere communication. For many Seminole people, learning their ancestral language is a deeply personal and transformative journey. It is a pathway to healing historical trauma, reclaiming a lost piece of their identity, and strengthening their connection to their heritage.

"There’s a sense of pride that comes with speaking your language," shares a young Seminole man who recently completed an advanced Maskókî course. "It’s like finding a missing piece of yourself. It connects me to my great-grandparents, to the land, to everything that makes us Seminole."

Beyond individual empowerment, language revitalization is a powerful act of self-determination and sovereignty. By preserving and promoting their languages, the Seminole people are asserting their distinct cultural identity in the face of centuries of assimilation attempts. It reinforces their right to define themselves, to govern themselves, and to transmit their unique worldview to future generations.

It’s also about intellectual sovereignty. Each language contains a unique framework for understanding the world, a way of categorizing nature, expressing emotions, and structuring thought that is distinct from English. To lose a language is to lose a unique perspective on existence, a body of knowledge accumulated over millennia. By revitalizing Mikasuki and Maskókî, the Seminole people are not just saving words; they are preserving entire systems of knowledge, ethics, and values.

A Future Spoken in Ancient Tongues

The journey to full language revitalization is a long and arduous one, but the Seminole people are walking it with unwavering determination. The classrooms, whether physical or virtual, are more than just places of learning; they are beacons of hope, laboratories of cultural resilience, and vibrant expressions of a nation’s will to survive and thrive.

As the sun sets over the cypress swamps of Florida or the rolling plains of Oklahoma, the sounds of Mikasuki and Maskókî are increasingly echoing through homes, community centers, and digital spaces. Each new learner, each word spoken, each phrase mastered, is a testament to the enduring spirit of the Seminole people – a people committed to ensuring that their ancient tongues will continue to tell their stories, sing their songs, and shape their future for generations to come. The voices of their ancestors, once threatened with silence, are rising again, strong and clear, carried forward by a generation determined to speak its heritage into existence.