Guardians of the Dawn: The Enduring Cultural Heartbeat of the Seneca Nation

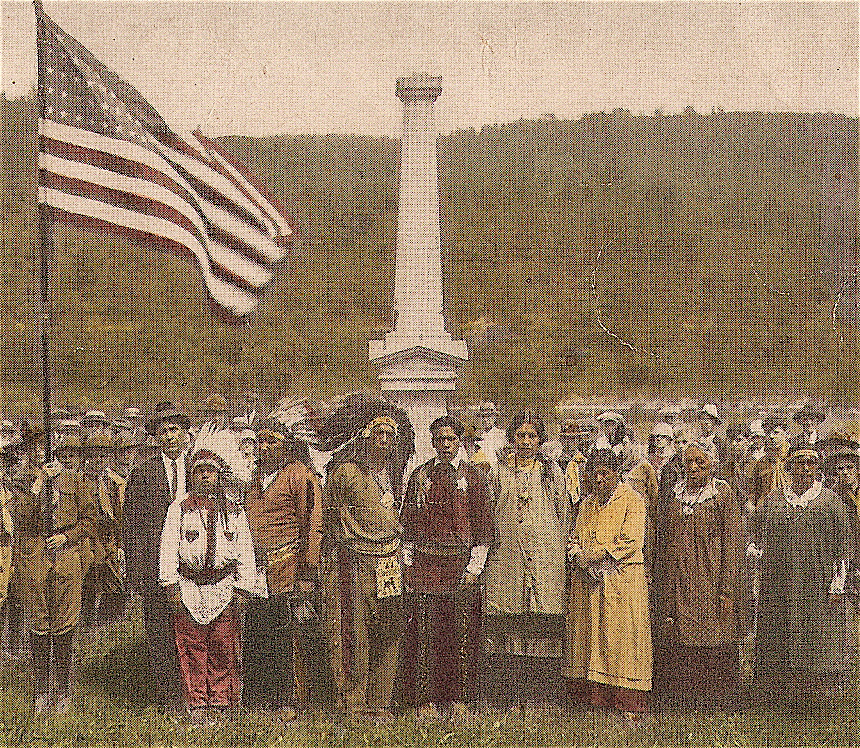

In the verdant embrace of what is now Western New York, where ancient forests whisper tales to flowing rivers, lies the ancestral homeland of the Seneca Nation of Indians. As the "Keepers of the Western Door" of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy, the Seneca people have for centuries safeguarded a profound cultural heritage, a tapestry woven from deep spiritual reverence, intricate social structures, and an unyielding connection to the natural world. Far from being relics of the past, these practices are vibrant, living traditions that continue to shape the identity, resilience, and future of the Onöndowa’ga:’ – the People of the Great Hill.

To truly understand Seneca culture, one must first grasp the foundational philosophy embedded in the Ohen:ton Karihwatehkwen, commonly known as the Thanksgiving Address. This isn’t merely a prayer; it’s a comprehensive worldview, recited at the opening and closing of every significant gathering, from solemn ceremonies to everyday meetings. It systematically acknowledges and gives thanks to every element of creation: the people, the Earth Mother, the waters, the fish, the plants, the animals, the trees, the birds, the Four Winds, the Thunderers, the Sun, the Moon, the Stars, and finally, the Great Spirit, or Creator.

"The Thanksgiving Address teaches us humility and gratitude," explains Elder Sarah Whitefeather (a composite character for illustrative purposes), a respected Seneca language speaker. "It reminds us that we are but one part of a vast, interconnected web of life, and that everything around us provides for our sustenance. It’s a daily practice of mindfulness, ensuring we live in balance and reciprocity." This profound respect for all living things underpins every aspect of Seneca cultural practice, from agriculture to governance.

At the heart of Seneca communal and spiritual life stands the Longhouse. Historically, these elongated timber structures housed multiple related families, symbolizing the extended familial bonds and collective identity of the Haudenosaunee. Today, while most Seneca live in modern homes, the Longhouse remains the spiritual and ceremonial center for traditional communities, particularly those who follow the Gaiwiio (Good Message) of Handsome Lake. It is within these sacred walls that ceremonies are held, social dances performed, and the ancient stories and teachings are passed down through generations. The very architecture of the Longhouse, with its curved roof resembling a turtle’s back, evokes the creation story of Turtle Island, emphasizing the Seneca’s deep roots in this land.

Agriculture forms another cornerstone of Seneca cultural life, epitomized by the "Three Sisters": corn, beans, and squash. These staple crops, planted together in a symbiotic relationship (corn provides a stalk for beans to climb, beans fix nitrogen in the soil, and squash shades the ground, retaining moisture and deterring weeds), are more than just food; they are spiritual gifts. The planting and harvesting of the Three Sisters are accompanied by specific ceremonies, thanking the Creator for their bounty and ensuring future abundance.

The ceremonial calendar of the Seneca Nation is intricately tied to the rhythms of the natural world, a testament to their intimate connection with the cycles of life. The Midwinter Ceremony (Ginó’gäh), held around late January or early February, is arguably the most significant. Lasting several days, it is a time of spiritual cleansing, renewal, and thanksgiving, marking the traditional New Year. Other vital ceremonies include the Maple Ceremony, celebrating the first harvest of maple sap; the Strawberry Ceremony (Da’dago:yahgwëh), honoring the first fruit of the season and its healing properties; the Green Corn Ceremony (Niayë:wëngë:), giving thanks for the ripening corn; and the Harvest Ceremony, celebrating the culmination of the agricultural year. Each ceremony involves specific songs, dances, and rituals, designed to maintain harmony between the people and the spiritual forces of the universe.

The Seneca social structure is equally profound, organized around a sophisticated clan system. Individuals are born into one of eight matrilineal clans: Bear, Wolf, Turtle, Snipe, Deer, Heron, Hawk, and Beaver (though Beaver is less common today). Matrilineal means that clan identity, property, and traditional leadership roles are passed down through the mother’s line. This system provides a strong sense of kinship, mutual responsibility, and governs marriage customs (one cannot marry within their own clan). Each clan has specific duties and responsibilities within the community and in ceremonies. Clan Mothers, respected elder women, play a crucial role in political and social life, responsible for nominating and advising the Hoyaneh (Chiefs) and ensuring the welfare of their clan members.

The Seneca language, Onöndowa’ga:’ Gawë:nö’, is more than a communication tool; it is a repository of history, philosophy, and identity. Its intricate grammar and rich vocabulary reflect the Seneca worldview, particularly their relationship with the natural world and their emphasis on action and process rather than static objects. Like many indigenous languages, Onöndowa’ga:’ Gawë:nö’ has faced severe threats due to historical assimilation policies. However, the Seneca Nation is deeply committed to its revitalization. Initiatives like the Seneca Language Department at their various territories are vigorously working to teach the language to new generations, understanding that language preservation is paramount to cultural survival. "When a language dies, a whole way of thinking, a whole universe of knowledge, goes with it," says Elder Whitefeather. "We are fighting to ensure that never happens to Onöndowa’ga:’."

Storytelling and oral tradition are vital components of Seneca culture. Before the advent of written language, history, laws, spiritual teachings, and practical knowledge were meticulously passed down through generations via spoken narratives. Elders, as keepers of this knowledge, hold immense respect and responsibility. These stories, often featuring animals, mythological beings, and historical figures, not only entertain but also impart moral lessons, explain natural phenomena, and reinforce cultural values. The Great Law of Peace (Kaianere’kó:wa), the foundational constitution of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, is itself a testament to the power and precision of oral tradition, having been preserved for centuries before being transcribed.

Artistic expression is another vibrant facet of Seneca culture. Traditional crafts like intricate beadwork, often adorning clothing and ceremonial regalia, feature symbolic designs that tell stories or represent clan affiliations. Basketry, traditionally made from black ash splints, showcases exceptional skill and artistry, with each basket often having a specific purpose, from gathering to storage. Music and dance are integral to ceremonies and social gatherings. The water drum, made from a hollowed log or wooden vessel partially filled with water, and various rattles made from gourds or turtle shells, provide the rhythmic heartbeat for traditional songs and dances, each with its own specific meaning and movement.

In the 21st century, the Seneca Nation continues to navigate the complexities of modernity while fiercely upholding their traditions. They operate successful businesses, manage their own education and healthcare systems, and actively engage in tribal sovereignty efforts. Yet, amidst these contemporary pursuits, the Longhouse remains a spiritual anchor, the Thanksgiving Address is recited daily, and the Three Sisters continue to nourish their communities. The challenges are real – the ongoing struggle against cultural appropriation, the impact of historical trauma, and the continuous effort to educate the wider public about their distinct identity – but so is their resilience.

"Our culture is not something we put on for ceremonies and then take off," states a young Seneca activist, Jamie Green (a composite character). "It’s who we are, every day. It’s in how we treat each other, how we care for the land, how we remember our ancestors, and how we prepare for the next seven generations. It’s a living, breathing thing."

The Seneca Nation of Indians, the Keepers of the Western Door, stand as a powerful testament to the enduring strength of cultural identity. Their practices are not just a historical legacy but a dynamic, evolving way of life that continues to offer profound lessons in sustainability, community, and gratitude for all of creation. Their heartbeat, echoing through the Longhouse, the cornfields, and the ancestral lands, remains strong, a beacon of wisdom for all who listen.