Echoes of the Land: Unveiling the Enduring Cultural Practices of the Shoshone People

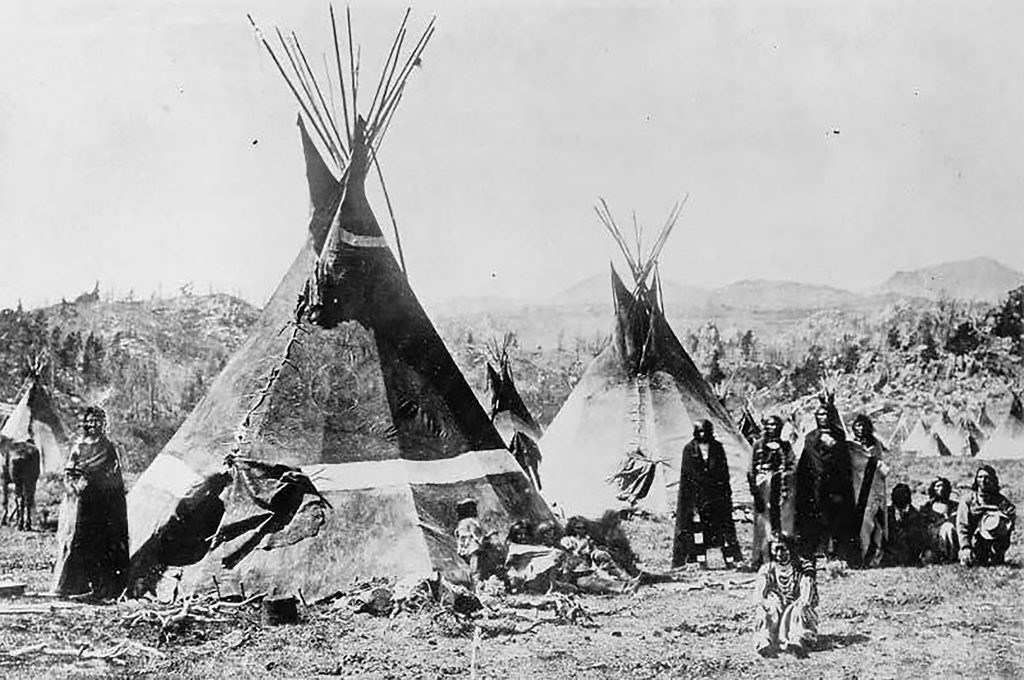

In the vast, undulating landscapes of the Great Basin, across the high plains of Wyoming, Idaho, Nevada, and Utah, a deep and enduring connection to the earth has shaped the lives and traditions of the Shoshone people for millennia. Far from being relics of the past, Shoshone cultural practices are vibrant, living traditions that continue to inform their identity, worldview, and way of life in the 21st century. Through resilience, adaptation, and a profound respect for their heritage, the Shoshone offer a powerful testament to the strength of Indigenous cultures.

The Shoshone, an Indigenous nation whose name is believed to derive from the Shoshoni word "Shoshoni" meaning "Valley Dwellers" or "Grass House People," are not a monolithic entity but a collection of distinct bands—Northern, Western, Eastern, and Goshute Shoshone—each with subtle variations in dialect and specific practices, yet united by a common linguistic root (Numic, part of the Uto-Aztecan family) and a shared spiritual foundation. Their history is one of remarkable adaptation, from nomadic hunter-gatherers following buffalo herds and harvesting seasonal plants to skilled horsemen, and now, to communities navigating the complexities of modern society while fiercely safeguarding their ancestral knowledge.

The Land as Teacher: A Foundation of Life

Central to Shoshone culture is an inseparable bond with the land. For generations, their lives were meticulously choreographed by the seasons and the availability of natural resources. This deep ecological knowledge was not merely survival instinct; it was a spiritual pact. "Our land is our mother, and we are part of her. If we hurt her, we hurt ourselves," a sentiment often echoed by Shoshone elders, encapsulates this profound connection.

Traditional Shoshone economy was based on a seasonal round. During warmer months, families would disperse into smaller groups, harvesting wild plants like camas lilies (Camassia quamash), whose starchy, onion-like bulbs were a crucial staple, often dug in communal gatherings. Pine nuts, gathered from piñon pines in the autumn, provided essential protein and fat, and were stored for winter. Hunting expeditions for deer, elk, antelope, and especially bison (after the introduction of horses) were communal efforts, requiring intricate knowledge of animal behavior and the landscape. Rivers and lakes provided fish, waterfowl, and other aquatic resources.

This nomadic existence fostered a sustainable worldview. Resources were never over-exploited; a sense of reciprocity ensured that what was taken was respected and that the land could replenish itself. This intimate relationship with the environment also meant that place names, geographical features, and natural phenomena were woven into their oral histories and spiritual narratives, serving as mnemonic devices for survival and cultural transmission.

Spiritual Heartbeat: Connecting to the Sacred

Shoshone spirituality is deeply animistic, perceiving the sacred in every aspect of the natural world. The Creator, often referred to as "Our Father" or "Tam A’ppeh," is honored through various ceremonies and daily practices. Dreams and visions hold immense significance, seen as direct communications from the spirit world, guiding individuals and providing insight. Animal spirits are revered as teachers and protectors, their characteristics embodying specific virtues or lessons.

One of the most profound and sacred ceremonies is the Sun Dance (Nʉn-nʉm-bi, or "Thirsting Dance"). This multi-day, arduous ceremony, typically held in mid-summer, is a powerful act of prayer, sacrifice, and renewal for the community and the world. Participants, often men, fast and dance for days, facing the sun, enduring physical hardship to seek visions, give thanks, or pray for healing. The construction of the Sun Dance lodge itself is a spiritual act, with each pole representing a prayer and the central pole embodying the Creator. It is a time for communal gathering, reaffirming spiritual commitment, and passing on ancient knowledge.

Another vital spiritual practice is the Sweat Lodge ceremony. Known as "A’kwihni," the sweat lodge is a dome-shaped structure, often made of willow branches covered with blankets or hides, heated by water poured over hot stones. It is a place of purification, prayer, healing, and spiritual renewal. Participants enter to cleanse their bodies and spirits, offer prayers, and connect with the Creator and ancestral spirits. It’s a space for reflection, seeking guidance, and fostering community bonds.

Community and Kinship: The Fabric of Life

The social structure of the Shoshone traditionally revolved around extended family units and bands. Kinship ties were paramount, defining roles, responsibilities, and relationships within the community. Cooperation and interdependence were not just ideals but necessities for survival.

Elders, revered as living libraries of knowledge, wisdom, and history, play a crucial role in cultural transmission. They are the storytellers, the language keepers, the ceremonial leaders, and the moral compass of the community. Children are raised communally, learning through observation, participation, and the stories told by their elders. This intergenerational learning ensures that traditions, values, and practical skills are passed down, fostering a strong sense of identity and belonging.

Sharing and reciprocity are core values. Resources, whether harvested food, game, or manufactured goods, were traditionally distributed equitably among band members, ensuring that no one went without. This communal spirit fostered strong social cohesion and mutual support.

Art, Story, and Language: Preserving Identity

Shoshone culture is rich in artistic expression, often deeply interwoven with daily life and spiritual beliefs. Basketry is a particularly notable art form. Shoshone women were renowned for their finely woven, often watertight baskets, used for gathering, cooking (by dropping hot stones into the water-filled baskets), and storage. Materials like willows, sumac, and various grasses were expertly prepared and woven into intricate patterns, each design often carrying symbolic meaning.

Beadwork and quillwork adorned clothing, bags, and ceremonial items, showcasing vibrant colors and geometric or animal designs. These were not merely decorative but often carried spiritual significance or told stories. Hide painting depicted historical events, visions, or individual accomplishments, serving as a visual record and a form of storytelling.

Oral tradition is the bedrock of Shoshone cultural preservation. Stories, myths, legends, and historical narratives are passed down through generations, teaching moral lessons, explaining the natural world, and preserving the collective memory of the people. Trickster tales, often featuring Coyote, teach about human foibles and wisdom in an entertaining way. Heroic narratives recount the deeds of ancestors and the origins of their customs.

The Shoshone language itself is a vital repository of cultural knowledge. It embodies their worldview, their connection to the land, and their unique way of understanding the world. However, like many Indigenous languages, it faced severe threats due to forced assimilation policies, including boarding schools that punished children for speaking their native tongues. Today, language revitalization efforts are a crucial part of cultural preservation, with communities establishing language classes, creating dictionaries, and encouraging young people to learn and speak Shoshone.

Resilience and Revitalization: A Living Legacy

The Shoshone people have endured immense adversity, from the trauma of colonization, land dispossession, and devastating massacres (such as the Bear River Massacre of 1863) to the forced assimilation policies of the 19th and 20th centuries. Despite these profound challenges, their culture has not only survived but continues to thrive.

Today, Shoshone communities across their ancestral lands are actively engaged in cultural revitalization. Powwows, while a pan-Indian phenomenon, serve as important gatherings for Shoshone people to celebrate their heritage through dance, song, and traditional regalia, fostering community spirit and educating younger generations. Cultural centers, museums, and educational programs are dedicated to preserving and sharing Shoshone history, language, and arts.

The Shoshone demonstrate a remarkable capacity for adaptation, integrating modern technologies and opportunities while holding fast to their core values. They continue to advocate for their sovereign rights, manage their lands, and protect sacred sites. The wisdom embedded in their traditional practices—ecological stewardship, communal responsibility, spiritual connection to the earth, and intergenerational learning—offers invaluable lessons for a world grappling with environmental crises and social fragmentation.

In the echoes of their ancient songs, the intricate patterns of their baskets, and the enduring strength of their language, the Shoshone people continue to tell a powerful story – a story of resilience, deep cultural roots, and an unwavering commitment to a way of life intrinsically connected to the pulse of the earth. Their practices are not just traditions; they are a living testament to the enduring spirit of a people, deeply rooted in their past yet vibrantly shaping their future.