Echoes of Hope: The Shoshone Ghost Dance and a People’s Enduring Spirit

In the twilight years of the 19th century, a profound spiritual movement swept across the American West, offering a beacon of hope to Indigenous peoples reeling from generations of relentless encroachment, broken treaties, and cultural decimation. While the Ghost Dance is often most famously associated with the Lakota and the tragic massacre at Wounded Knee, its genesis and embrace stretched across numerous Native American nations, including the Shoshone. For the Shoshone people, scattered across their ancestral lands in what is now Wyoming, Idaho, Utah, and Nevada, the Ghost Dance was not merely a fleeting religious fad, but a deeply resonant expression of resilience, a spiritual last stand against an existential threat, and a testament to an enduring cultural spirit.

To understand the profound appeal of the Ghost Dance among the Shoshone, one must first grasp the devastating context of their lives. By the late 1880s, their traditional way of life had been all but annihilated. The vast buffalo herds, the very lifeblood of the plains tribes, were gone, slaughtered to near extinction by white hunters and a deliberate U.S. government policy to starve Native Americans into submission. Their ancestral lands, once boundless, had been drastically reduced to isolated reservations, often on marginal ground, where they were subjected to forced assimilation policies, dependent on meager government rations, and plagued by disease.

"The buffalo were gone, the land was shrinking, and a way of life was vanishing into the dust of broken promises," explains historian Dr. Sarah Miller, specializing in Native American studies. "The despair was palpable. People were starving, their children were dying, and their spiritual world was under constant attack. They desperately needed something to believe in."

It was into this crucible of despair that the message of the Ghost Dance arrived. Its origins lay with a Paiute prophet named Wovoka (also known as Jack Wilson) from Nevada. In 1889, during a solar eclipse, Wovoka experienced a profound vision. He claimed to have ascended to the spirit world, where he spoke with God. God, he reported, instructed him to teach his people a new way of life: one of peace, hard work, honesty, and an abstention from alcohol. If they followed these tenets and performed a specific circular dance, a miraculous transformation would occur. The dead ancestors would return, the buffalo would reappear, the white settlers would vanish (or, in some interpretations, simply be absorbed into a harmonious new world), and the earth would be renewed to its pristine state.

Wovoka’s message was inherently peaceful, emphasizing non-violence and moral rectitude. He urged his followers, "Do not hurt anybody, do not quarrel." He also taught them a simple, circular dance, performed in groups, often for days on end, which would induce trance-like states and visions, allowing participants to commune with the spirits and experience the coming renewal.

The news of Wovoka’s vision spread like wildfire across the intertribal networks of the West, carried by messengers who traveled hundreds of miles. For the Shoshone, who had long maintained strong ties with their Paiute kin and other neighboring tribes, the message found fertile ground. Shoshone delegations traveled to Nevada to meet Wovoka, bringing back his teachings and the dance to their communities on reservations like Wind River in Wyoming, Fort Hall in Idaho, and Duck Valley straddling the Idaho-Nevada border.

The Shoshone embraced the Ghost Dance with fervent hope, interpreting Wovoka’s prophecy through their own cultural lens. While the core promise of a revitalized world resonated deeply, their focus was often less on the violent expulsion of white settlers and more on spiritual renewal, the return of lost loved ones, and the re-establishment of a harmonious balance with the land and the spirit world. For them, it was a way to reclaim agency in a world where they had none, a spiritual resistance against cultural annihilation.

"The Shoshone saw in the Ghost Dance a path to cultural survival, a way to connect with their ancestors and reaffirm their identity," notes Professor John Stands In Timber, a scholar of Native American history. "It was a collective prayer, a desperate plea for the world to be set right again, and a powerful act of community cohesion."

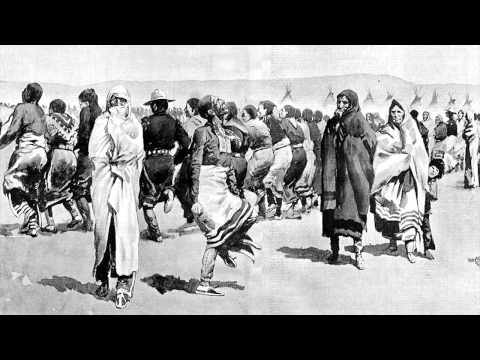

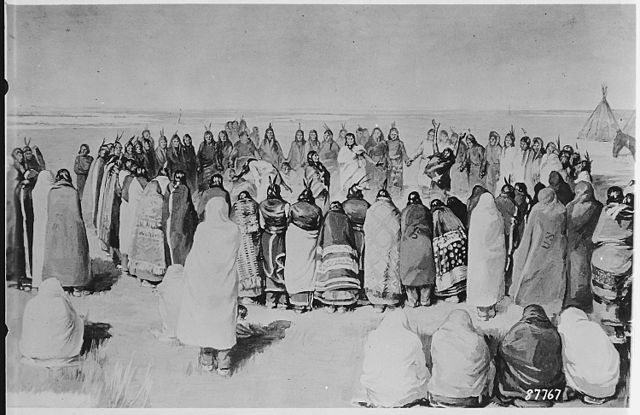

The dance itself was a central component. Participants, often dressed in ceremonial clothing, would gather in a large circle, holding hands, and move in a slow, shuffling rhythm to the accompaniment of sacred songs. The dance could last for hours, sometimes days, with little food or water. As the dancers entered trance states, they would fall to the ground, experiencing vivid visions of deceased relatives, bountiful buffalo herds, or a transformed earth. These visions served to reinforce the prophecy, providing powerful personal validation of the coming changes. The songs, often revealed during visions, were unique to each tribe’s interpretation, blending traditional melodies with elements of Wovoka’s teachings.

For the Shoshone, the Ghost Dance offered an emotional and spiritual release from the crushing weight of their circumstances. It provided a sense of purpose and collective identity at a time when their traditional social structures were under assault. It was a reaffirmation of their spiritual beliefs, even as missionaries sought to convert them to Christianity. The syncretic nature of the Ghost Dance, incorporating some Christian elements like a messianic figure and a renewed earth, may also have made it more accessible to some who had been exposed to missionary teachings.

However, the rapid spread and fervent adoption of the Ghost Dance did not go unnoticed by the U.S. government and white settlers. Misunderstanding and fear quickly took root. The peaceful, spiritual nature of the movement was largely ignored or deliberately misinterpreted. To the fearful settlers and the increasingly paranoid military, the sight of hundreds of Native Americans dancing for days, seemingly in a frenzy, dressed in ceremonial attire that sometimes included "Ghost Shirts" (believed by some to be bulletproof, though this was largely a Lakota interpretation, not central to Wovoka’s teaching), was perceived as a prelude to armed insurrection.

Indian agents, tasked with controlling reservation populations, often sent alarmist reports to Washington, exaggerating the "threat" posed by the dancers. They viewed the movement as a direct challenge to their authority and the assimilation policy. This fear ultimately culminated in the tragic events at Wounded Knee Creek in December 1890, where the U.S. Army massacred hundreds of Lakota men, women, and children, effectively crushing the Ghost Dance movement on the plains.

For the Shoshone, while they were fervent adherents, their experience with the Ghost Dance largely avoided such direct, violent confrontation with the U.S. military. This was due to a combination of factors: their geographical dispersal, the less centralized nature of their bands compared to the powerful Plains tribes, and perhaps, crucially, the specific interpretations and leadership within Shoshone communities that continued to emphasize peace and spiritual renewal over armed resistance. While agents and military personnel on Shoshone reservations certainly viewed the dances with suspicion and attempted to suppress them, the widespread massacre that befell the Lakota was averted.

Despite its ultimate failure to literally bring back the dead or make the white man disappear, the Ghost Dance left an indelible mark on the Shoshone people. It reinforced their resilience, their capacity for spiritual innovation, and their commitment to cultural survival. Even after the official suppression of the movement, elements of the Ghost Dance persisted underground or subtly integrated into other spiritual practices. It became part of their collective memory, a powerful story of hope and resistance in the face of overwhelming odds.

In the long arc of Shoshone history, the Ghost Dance stands as a poignant symbol. It was a desperate, yet profoundly spiritual, response to an existential crisis. It demonstrated the power of faith and collective action in the face of despair, and the enduring human need for hope, even when all seems lost. More than a century later, the echoes of the Ghost Dance continue to resonate in the spiritual practices and cultural identity of the Shoshone people, a testament to an unyielding spirit that refused to be extinguished. It reminds us that even in the darkest hours, the human spirit can find a way to dance, to sing, and to dream of a better world.