Echoes Across the Sagebrush: The Enduring Story of Shoshone Historical Lands

Imagine a territory so vast and varied it encompassed towering snow-capped peaks, arid desert basins, life-giving rivers, and rolling plains. A domain where the land dictated the rhythms of life, where every plant and animal held significance, and where human existence was interwoven with the very fabric of the earth. This was the traditional homeland of the Shoshone people, a sprawling dominion that once stretched across what is now Wyoming, Idaho, Nevada, Utah, and parts of California, Oregon, and Montana. Their story is not merely one of geographical expanse, but of profound connection, resilience, and an enduring struggle for recognition and stewardship of lands that shaped their identity for millennia.

For the Shoshone, known in their own language as "Newe" – "The People" – the land was not merely property to be owned or exploited; it was kin, a sacred entity that provided sustenance, spiritual guidance, and a sense of belonging. Their historical territory, often referred to as Newe Sogobia, was a mosaic of diverse ecosystems, each demanding unique adaptations and offering distinct resources. From the Eastern Shoshone, who followed the buffalo across the plains of Wyoming, to the Western Shoshone and Goshute, who expertly navigated the harsh Great Basin deserts, utilizing every resource from pine nuts to small game, their lifeways were a testament to their deep ecological knowledge and ingenuity.

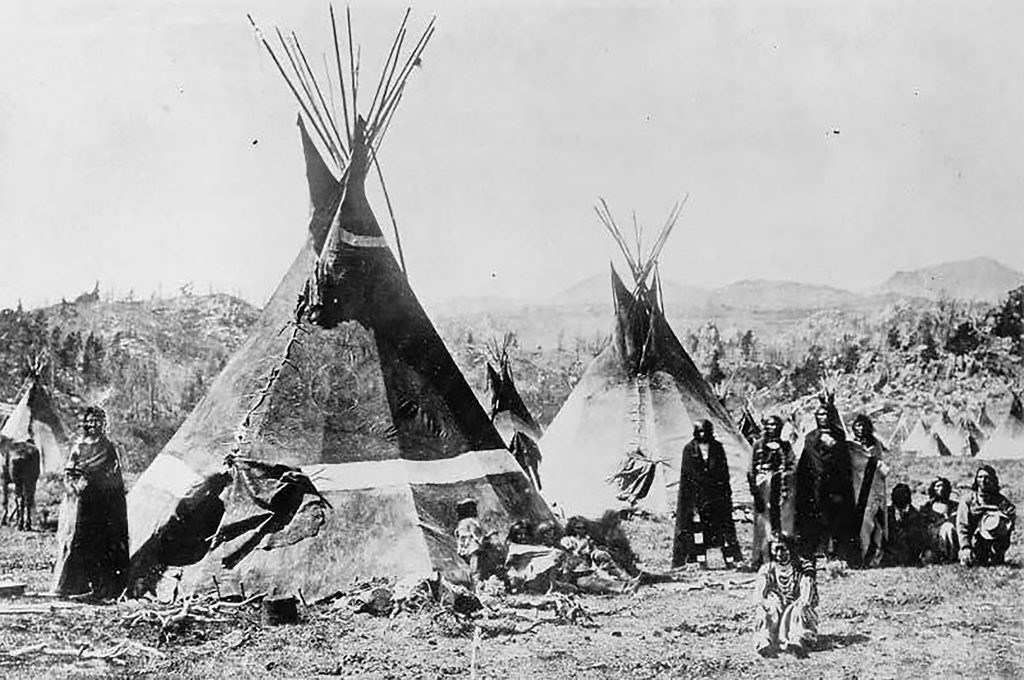

Before the arrival of Euro-Americans, the Shoshone lived a largely nomadic or semi-nomadic existence, moving with the seasons to harvest nature’s bounty. In the spring, they gathered roots and berries; in summer, they hunted deer, elk, and antelope; autumn brought the critical pine nut harvest in the Great Basin, a staple that could sustain them through winter; and for the Plains Shoshone, the buffalo hunt was central to their economy and culture. Their movements were not random but followed ancient pathways, guided by intimate knowledge of water sources, animal migrations, and plant cycles. "Our people understood the land like a book," shared a contemporary Shoshone elder, reflecting on ancestral wisdom. "They knew where the water was, where the food was, and how to live in balance with it all."

This intricate relationship with the land also defined their spiritual and social structures. Sacred sites, often prominent geological features like mountains or hot springs, were places of ceremony, healing, and connection to the ancestors. Oral traditions, passed down through generations, recounted the creation of the land and the origins of their people, reinforcing their inherent bond to specific territories. Boundaries, though not fenced or surveyed, were understood through shared history, resource use, and inter-tribal agreements.

The mid-19th century, however, brought an unprecedented wave of change that would irrevocably alter the landscape of Newe Sogobia and the lives of its inhabitants. The California Gold Rush of 1849, followed by subsequent mineral discoveries across the West, transformed a trickle of explorers and trappers into a torrent of settlers, miners, and adventurers. Wagon trails, like the Oregon Trail and the California Trail, cut directly through Shoshone lands, disrupting traditional hunting grounds and water sources. The concept of "Manifest Destiny"—the belief in America’s divinely ordained right to expand westward—fueled this relentless encroachment, viewing the vast lands as "empty" and ripe for exploitation, despite millennia of indigenous habitation.

The Shoshone, initially encountering a mix of curiosity and caution with the newcomers, soon faced the harsh realities of invasion. Their lands, once a source of life, became a battleground for survival. As resources dwindled and violence escalated, the U.S. government began to impose its own system of land ownership through treaties – agreements often made under duress, with profound misunderstandings of indigenous land concepts, and frequently broken.

One of the most significant was the Treaty of Fort Bridger in 1863 (and later, 1868), which attempted to define the territories of the Eastern Shoshone and Bannock tribes. While these treaties acknowledged vast Shoshone territories, they also marked the beginning of their formal reduction. The Ruby Valley Treaty of 1863, signed by the Western Shoshone, also recognized a vast traditional homeland but was later interpreted by the U.S. government as a cession of land, rather than a peace treaty allowing passage, as the Shoshone understood it. This fundamental difference in understanding—the Western concept of land ownership versus the indigenous concept of stewardship and communal use—led to generations of conflict and injustice.

As settlers flooded in, violence against the Shoshone escalated. The most horrific example was the Bear River Massacre in January 1863, where U.S. Army troops attacked a peaceful Shoshone encampment near present-day Preston, Idaho, killing hundreds of men, women, and children. This brutal act, one of the deadliest massacres of Native Americans in U.S. history, served as a chilling precursor to the forced removal and confinement of the Shoshone onto reservations – shrinking parcels of land far removed from their traditional hunting and gathering grounds.

The establishment of reservations like Wind River in Wyoming, Fort Hall and Duck Valley in Idaho/Nevada, and the Goshute Reservations in Utah/Nevada, marked a profound disruption. Shoshone people, whose identities were inextricably linked to their mobility and the vastness of their ancestral lands, were now confined to fixed boundaries. This confinement aimed to dismantle their traditional lifeways, assimilate them into Euro-American society, and open up the rest of their vast domain for white settlement, ranching, and resource extraction.

Despite immense hardship, cultural suppression, and the devastating loss of life and land, the Shoshone people endured. Their resilience is a testament to their deep cultural roots and the strength of their connection to the land, even in its diminished state. On the reservations, they adapted, incorporating new technologies and economic practices while striving to maintain their languages, ceremonies, and oral histories. Many quietly resisted assimilation, passing on traditional knowledge and values in the face of immense pressure.

In the latter half of the 20th century and into the 21st, the struggle for land and sovereignty continued, often shifting from armed conflict to legal battles. The Western Shoshone, for instance, have been engaged in a prolonged legal dispute over the lands recognized by the Ruby Valley Treaty, arguing that their ancestral territory was never legally ceded. This dispute, which includes areas rich in gold and other minerals, has highlighted the ongoing tension between indigenous land rights and modern resource development. The Shoshone have also been vocal advocates for environmental protection, opposing projects like the proposed Yucca Mountain nuclear waste repository in Nevada, which lies within their sacred lands. Their stance often reflects their traditional worldview that the land is not a commodity but a living entity that must be protected for future generations.

Today, the Shoshone nation is a vibrant collection of distinct bands and tribes, each with its own unique history and challenges, but united by a shared heritage and an enduring bond to their ancestral lands. While the vastness of Newe Sogobia has been significantly reduced, the spirit of the land and its people remains unbroken. Efforts are ongoing to revitalize languages, preserve cultural practices, and educate younger generations about their history and responsibilities as stewards of the earth. Land reclamation, co-management agreements with federal agencies, and environmental advocacy are key components of their modern fight for self-determination.

The story of Shoshone historical lands is not just one of loss, but of profound resilience and an unyielding commitment to heritage. It serves as a powerful reminder that for indigenous peoples, land is not merely a resource; it is the very essence of identity, culture, and survival. The echoes of their ancestors still resonate across the sagebrush, reminding us of a time when the land was vast and free, and of the enduring spirit of the Shoshone people, who continue to protect and honor their sacred earth. Their journey, marked by both tragedy and triumph, offers vital lessons on stewardship, sovereignty, and the unbreakable bond between a people and their ancestral home.